高血糖损伤血管内壁是导致糖尿病并发症的统一机制

Indirect Effects Of High Glucose

The missing link: A single unifying mechanism for diabetic complications

Author links open overlay panelTakeshiNishikawaDianeEdelsteinMichaelBrownlee

Department of Metabolic Medicine, Kumamoto University School of Medicine, Kumamoto, Japan

Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Diabetic Research Center, Bronx, New York, USA

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.07705.xGet rights and content

Under an Elsevier user licenseopen archive

The missing link: A single unifying mechanism for diabetic complications. A causal relationship between chronic hyperglycemia and diabetic microvascular disease, long inferred from various animal and clinical studies, has now been definitely established by data from the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT), a multicenter, randomized, prospective, controlled clinical study. A relationship between chronic hyperglycemia and diabetic macrovascular disease in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) is also supported by the Kumamoto study. How does hyperglycemia induce the functional and morphologic changes that define diabetic complications? Vascular endothelial cells are a major target of hyperglycemic damage, but the mechanisms underlying this damage remain incompletely understood. Three seemingly independent biochemical pathways are involved in the pathogenesis: glucose-induced activation of protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms; increased formation of glucose-derived advanced glycation end products; and increased glucose flux through the aldose reductase pathway. The relevance of each of these three pathways is supported by animal studies in which pathway-specific inhibitors prevent various hyperglycemia-induced abnormalities. Hyperglycemia increases reactive oxygen species (ROS) production inside cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells. In this paper, we show that ROS may activate aldose reductase, induce diacylglycerol, activate PKC, induce advanced glycation end product formation, and activate the pleiotropic transcription factor nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κ;B). These data demonstrate that a single unifying mechanism of induction, increased production of ROS, serves as a causal link between elevated glucose and each of the three major pathways responsible for diabetic damage.

Previous article in issueNext article in issue

Keywords

diabetes mellitushyperglycemiaprotein kinase CNF-κ;B

A causal relationship between chronic hyperglycemia and diabetic microvascular disease, long inferred from various animal and clinical studies1, has now been definitely established by data from the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT), a multicenter, randomized, prospective, controlled clinical study. The DCCT study demonstrated conclusively that the relative risks for the development of diabetic complications increased with increasing levels of mean hemoglobin (Hb) A1c. Patients with type 1 diabetes whose intensive insulin therapy produced HbA1c levels 2% lower than those receiving conventional insulin therapy had a 76% lower incidence of retinopathy, a 54% lower incidence of nephropathy, and a 60% reduction in neuropathy. A relationship between levels of chronic hyperglycemia and diabetic microvascular and macrovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes has also been found in several studies2., 3., 4.. Thus, hyperglycemia is the primary initiating factor in the pathogenesis of diabetic complications.

.png)

The distinguishing characteristic of cells that have been damaged by hyperglycemia is their lack of down-regulation of glucose transport when extracellular glucose is elevated. Vascular smooth muscle cells that have not been damaged by hyperglycemia show an inverse relationship between glucose concentration and glucose transport measured as 2-deoxyglucose uptake. In contrast, vascular endothelial cells, a major target of hyperglycemic damage, show no significant change in glucose transport when glucose concentration is elevated. Thus, intracellular hyperglycemia appears to be the major determinant of diabetic tissue damage5.

Intracellular hyperglycemia causes tissue damage by mechanisms that can be grouped into two categories. One category of mechanisms involves repeated acute changes in cellular metabolism that are reversible when euglycemia is restored. Another category of mechanisms involves cumulative changes in long-lived macromolecules that persist despite restoration of euglycemia. These mechanisms are influenced by genetic determinants of susceptibility or resistance to hyperglycemic damage.

Four major hypotheses about how hyperglycemia causes diabetic complications have generated a large amount of data, as well as several clinical trials based on specific inhibitors of these mechanisms: formation of reactive oxygen species; increased activity of aldose reductase; activation of protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms; and increased formation of advanced glycation end products. No current unifying hypothesis links these four mechanisms, but either polyol pathway-induced redox changes [decreased nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (reduced form) (NADPH)/nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+) and increased nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (reduced form) (NADH)/nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) ratios] or hyperglycemia-induced formation of reactive oxygen species could potentially account for all of the other biochemical abnormalities.

Hyperglycemia increases intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxidation. In aortic endothelial cells, 30 mmol/L glucose increased ROS formation [measured as dichlorofluorescein (DCF)] by 250% within 24 hours, and resultant lipid peroxidation (measured as malondialdehyde) by 330% by 168 hours. Thus, hyperglycemia rapidly increases intracellular ROS production in cells affected by diabetic complications6.

The enzyme aldose reductase converts various aldehydes (such as 2-oxo-aldehydes and those derived from lipid peroxidation) to inactive alcohols. NADPH is the cofactor in both this reaction and also in the regeneration of glutathione by glutathione reductase. The activity of aldose reductase is reversibly down-regulated by nitric oxide modification of a cysteine residue in the enzyme's active site. ROS appear to reduce nitric oxide levels and thus may activate aldose reductase7., 8., 9.. In a euglycemic environment, oxidant stress (i.e., ROS) increases the concentration of toxic aldehydes. At the same time, nitric oxide levels are reduced, converting aldose reductase to a higher activity form. Glutathione levels are unaffected, and the reactive aldehydes are detoxified.

In a hyperglycemic environment, oxidant stress (ROS) increases, and the reactive aldehydes are then detoxified. However, in contrast to the euglycemic state, increased intracellular glucose concentration results in increased enzymatic conversion of glucose to the polyalcohol sorbitol, with concomitant decreases in NADPH and glutathione. In cells in which aldose reductase activity is sufficient to deplete glutathione, hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress is augmented. Sorbitol is oxidized to fructose by the enzyme sorbitol dehydrogenase (SDH). In cells in which sorbitol dehydrogenase activity is high, this may result in an increased NADH : NAD+ ratio. This could increase de novo synthesis of diacylglycerol (DAG) by inhibition oxidation of triose phosphates, thereby activating PKC.

The effect of aldose reductase inhibition is most striking on diabetes-induced decreases in nerve conduction velocity. In dogs with diabetes, conduction became significantly less than normal within 42 months10. Conduction velocity in aldose reductase inhibitor-treated dogs remained statistically equal to normal throughout the 5-year study. In contrast, aldose reductase inhibition had no effect on the development of diabetic retinopathy, perhaps due to the low aldose reductase activity in retinal vascular cells10.

The third mechanism by which intracellular hyperglycemia damages tissue is PKC activation. Hyperglycemia increases DAG content, in part by de novo synthesis and possibly also by phosphatidylcholine hydrolysis. Increased DAG activates PKC, primarily the β and δ; isoforms. Activated PKC increases the production of cytokines and extracellular matrix (ECM), the fibrinolytic inhibitor plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1), and the vasoconstrictor endothelin-1. PKC is also a mediator of vascular endothelial growth factor activity. These changes contribute to basement membrane thickening, vascular occlusion, increased permeability, and activation of angiogenesis11. ROS also activate PKC in vascular endothelial cells. As ROS-producing H2O2 increases, it activates PKC. The mechanism appears to involve direct or indirect activation of phospholipase D, which hydrolyzes phosphatidylcholine to produce DAG. ROS could also increase DAG through increased de novo synthesis resulting from ROS inhibition of the enzyme glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase12,13.

The significance of this mechanism has been established by studies of an isoform-specific PKC inhibitor in diabetic animals. Diabetes increased mean retinal circulation time in rats from 0.67 second to 1.40 seconds. Treatment of diabetic rats with the PKCβ inhibitor LY 333531 reduced the time to 0.87 second at the highest dose tested. Similarly, diabetes increased glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in rats from a mean of 3.0 to 4.6 mL/min. Treatment of diabetic rats with the PKCβ inhibitor LY 333531 normalized the mean glomerular filtration rate (GFR) at the highest doses tested. Similarly, diabetes increased the albumin excretion rate in rats from a mean of 1.6 to 11.7 mg/day. Treatment of diabetic rats with the PKCβ inhibitor LY 333531 reduced the mean albumin excretion rate to 4.9 mg/day at the highest dose tested14.

The final mechanism by which intracellular hyperglycemia damages susceptible tissues is by increasing the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). AGEs can arise from autooxidation of glucose to glyoxal, decomposition of the Amadori product to 3-deoxyglucosone, and fragmentation of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate to methylglyoxal. These reactive dicarbonyls react with amino groups of proteins to form AGEs. Methylglyoxal and glyoxal are detoxified by the glyoxalase system. All three AGE precursors are also substrates for other reductases as well15,16. Intracellular production of AGE precursors damages target cells by three general mechanisms. First, intracellular protein glycation alters protein function. Second, ECM modified by AGE precursors has abnormal functional properties. Third, plasma proteins modified by AGE precursors bind to AGE receptors on adjacent cells such as macrophages, thus inducing receptor-mediated ROS production that activates nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κ;B) and expression of pathogenic gene products, including cytokines and hormones17.

An example of intracellular protein glycation is the increase in macromolecular endocytosis in endothelial cells by the AGE-precursor methylgloxal. Exposure to 30 mmol/L glucose increased macromolecular endocytosis by GM7373 endothelial cells stably transfected with neo 2.2-fold. In contrast, when increased methylglyoxal accumulation was prevented by overexpressing the enzyme glyoxalase I in these cells, 30 mmol/L glucose did not increase macromolecular endocytosis15. An example of matrix modification by AGE-precursors is the increased permeability to albumin of glomerular basement membrane modified by AGEs. Ultrafiltration of albumin (Js) by AGE-modified glomerular basement membrane is significantly increased compared with ultrafiltration of albumin by unmodified glomerular basement membrane over a range of different filtration pressures18.

Five AGE-binding proteins have been identified: the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), p60, p90, galectin-3, and the scavenger receptor type II. RAGE is a novel member of the immunoglobin superfamily, whose ligation generates ROS and activates the pleiotropic transcription factor NF-κ;B. p60 exhibits 95% identity to OST-48, a component of the oligosaccharyltransferase complex in microsomal membranes, and p90 has significant sequence homology with human 80K-H, a PKC substrate. Galectin-3, a carbohydrate-binding protein, also binds AGEs. The type II macrophage scavenger receptor binds AGEs and mediates their uptake by endocytosis. To date, only RAGE has actually been shown to transduce signals initiated by AGE-ligand binding. The signal transduction pathway involves the generation of ROS, which then activate the pleiotropic transcription factor NF-κ;B19., 20., 21., 22..

AGE-modified protein binding to specific receptors on macrophages and endothelial cells cause pathologic changes in diabetic blood vessels by inducing the expression of pathogenic gene products. On macrophages and mesangial cells, binding stimulates production of tumor necrosis factor α, (TNF-1) interleukin-1, insulin-like growth factor-1, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor at levels that increase proliferation of smooth muscle cells and increase matrix production. On endothelial cells, binding induces changes in gene expression that are procoagulatory, and increases expression of leukocyte-binding vascular adhesion molecule-123.

The significance of AGEs as mediators of glucose-induced pathology in diabetic target tissues has been established by using an inhibitor of AGE formation. The effects of an AGE inhibitor (aminoguanidine) on diabetic pathology have been investigated in retina, kidney, nerve, and artery. In experimental animals, development of all pathognomonic abnormalities examined was inhibited 85% to 90%. These include the development of retinal acellular capillaries and retinal microaneurysms, increased urinary albumin excretion and mesangial fraction volume, decreased motor and sensory nerve conduction velocity and action-potential amplitude, and diminished arterial elasticity and increased arterial fluid filtration17.

It has been proposed that a potential relationship may exist between polyol pathway-induced redox changes and the three other biochemical mechanisms underlying diabetic complications. In this scheme, increased glucose flux through the polyol pathway could decrease the NADPH : NADP+ ratio, thereby reducing glutathione reductase activity and increasing oxidative stress. In those cells where significant oxidation of sorbitol to fructose occurs, increased sorbitol flux through this pathway could also increase the NADH : NAD+ ratio, thereby blocking glycolysis at the level of triose phosphates and increasing formation of α-glycerol phosphate, a precursor of DAG. In addition, increased triose phosphate concentrations produce more of the most potent AGE-precursor, methylgloxal. The difficulties with this attempt at a unifying theory of diabetic complications is that aldose reductase activity is low in several major target cells damaged in diabetes, such as endothelial cells. In addition, experimentally, aldose reductase inhibitors have no effect on hyperglycemia-induced increases in endothelial cell DAG, contrary to what is predicted24,25. An alternative unifying mechanism is hyperglycemia-induced ROS production. ROS may activate aldose reductase, induce DAG, activate PKC, induce advanced glycation end product formation, and activate the pleiotropic transcription factor NF-κ;B6., 7., 8., 12., 26., 27..

Glucose-induced damage in cells of arteries may be further accelerated by insulin resistance. Insulin resistance may damage arteries indirectly by exacerbating known risk factors for vascular damage. Insulin resistance alone or combined with hyperinsulinemia is associated with atherogenic changes in plasma lipoproteins, increased PAI-1, and hypertension. This association has been termed “Syndrome X”28. Alternatively, we have proposed that insulin resistance in vascular cells may promote damage by inhibiting antiatherogenic gene expression. Selective resistance to insulin action in the phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase signaling pathway may reduce antiproliferative nitric oxide production and interfere with insulin's inhibitory effect on TNF and angiotensin II's stimulation of PAI-1 and intracellular adhesion molecule expression9.

The susceptibility to damage by hyperglycemia, at least for the kidney and retina, is determined by unknown genetic factors. For example, in patients with type 1 diabetes, the cumulative incidence of overt proteinuria levels off at 27%. After 34 years of diabetes, the cumulative incidence of end-stage renal disease in affected patients is 21.4%. These data suggest that only a subset of patients are susceptible to the development of clinical nephropathy29. Familial clustering of diabetic nephropathy also strongly suggests a major genetic effect. In one study, the nephropathy risk for diabetic siblings of an affected case was 83%, whereas the risk for diabetic siblings of an unaffected patient was 17%. In another study, the risks were 33% and 10%, respectively30.

A major feature of hyperglycemic damage that is unaccounted for by current theories of the pathogenesis of diabetic complications is the so-called “hyperglycemic memory.” This term refers to the development of retinopathy during posthyperglycemic normoglycemia. In the study that initially described this, normal dogs were compared with dogs with diabetes with either poor control for 5 years, good control for 5 years, or poor control for 21/2 years (P→Ga) followed by good control for the next 21/2 years (P→Gb). HbA1 values for both the good control group and the P→Gb group were identical to the normal group. Quantitation of retinal microaneurysms and acellular capillaries in this study showed that lesions of diabetic retinopathy developed during 5 years of poor control. Good control prevented nearly all of this pathology. After 21/2 years of poor control, retinopathy was absent. However, despite the institution of good control in this group after 21/2 years, retinopathy developed over the next 21/2 years to an extent almost equal to the 5-year poor control group31.

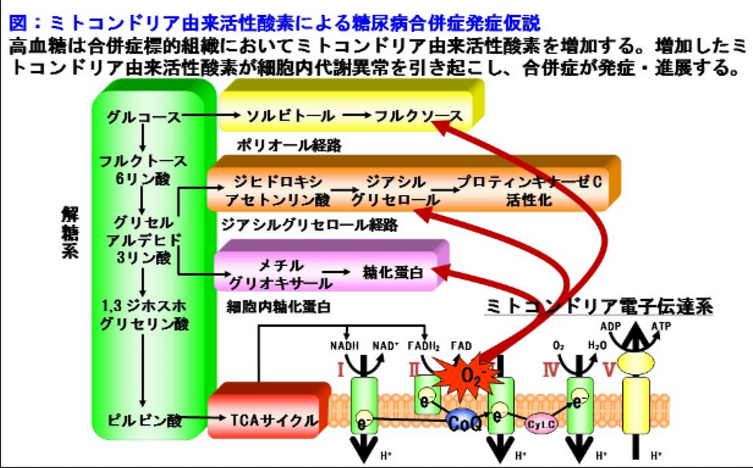

A potential mechanism for hyperglycemic memory could involve two stages: induction and perpetuation. Induction could be explained by hyperglycemia-induced increases in ROS, which may be a consequence of increased reducing equivalents generated from increased glucose metabolism flowing through the mitochondrial electron transport chain. Increased ROS would not only cause cellular dysfunction but also induce mutations in mitochondrial DNA32,33. Perpetuation (i.e., hyperglycemic memory) would occur because mitochondrial DNA mutated by hyperglycemia-induced ROS would encode defective electron transport chain subunits. These defective subunits would cause increased ROS production by the electron transport chain at physiologic concentrations of glucose and glucose-derived reducing equivalents. Such a mechanism could explain the observation that in human patients with diabetes with functioning pancreatic transplants, renal pathology continues to progress for at least 5 years after diabetes has been cured31.

If future work substantiates this hypothesis for a unifying mechanism of glucose-accelerated aging of vascular and neurologic tissues, it may provide the basis for the development of new pharmaceutical agents for the treatment of these problems.

https://s.click.taobao.com/oCymNMw

https://s.click.taobao.com/lBxmNMw

References

1.

J. Skyler

Diabetic Complications: The importance of glucose control

Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America (edited by Brownlee MB, King GL), WB Saunders, Philadelphia (1996)

2.

Y. Ohkubo, H. Kishikawa, E. Araki, T. Miyata, S. Isami, S. Motoyoshi, Y. Kojima, N. Furuyoshi, M. Shichiri

Intensive insulin therapy prevents the progression of diabetic microvascular complications in Japanese patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: Randomized prospective 6-year study

Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 28 (1995), p. 103

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in Scopus

3.

J. Kuusisto, L. Mykkanen, K. Pyorala, M. Laakso

NIDDM and its metabolic control predict heart disease in elderly subjects

Diabetes, 43 (1994), pp. 960-967

CrossRefView Record in Scopus

4.

N. Kaiser, S. Sasson, E.P. Feener, N. Boukobza-Vardi, S. Higashi, D.E. Moller, S. Davidheiser, R.J. Przybylski, G.L. King

Differential regulation of glucose transport and transporters by glucose in vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells

Diabetes, 42 (1993), pp. 80-89

CrossRefView Record in Scopus

5.

I. Giardino, D. Edelstein, M. Brownlee

BCL-2 expression or antioxidants prevent hyperglycemia-induced formation of intracellular advanced glycation end products in bovine endothelial cells

J Clin Invest, 97 (1996), pp. 1422-1428

CrossRefView Record in Scopus

6.

A. Chandra, S. Srivastava, J.M. Petrash, A. Bhatnagar, S.K. Srivastava

Active site modification of aldose reductase by nitric oxide donors

Biochim Biophys Acta, 131 (1997), pp. 217-222

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in Scopus

7.

G.M. Pieper, P. Langenstroer, W. Siebeneich

Diabetic-induced endothelial dysfunction in rat aorta: role of hydroxyl radicals

Cardiovascular Res, 34 (1997), pp. 145-156

CrossRefView Record in Scopus

8.

G.L. King, M.B. Brownlee

The cellular and molecular mechanisms of diabetic complications

Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America (edited by Brownlee MB, King GL), WB Saunders, Philadelphia (1996)

9.

R.L. Engerman, T.S. Kern, M.E. Larson

Nerve conduction and aldose reductase inhibition during 5 years of diabetes or galactosaemia in dogs

Diabetologia, 37 (1994), pp. 141-144

CrossRefView Record in Scopus

10.

D. Koya, G.L. King

Protein kinase C activation and the development of diabetic complications

Diabetes, 47 (1998), pp. 859-867

CrossRefView Record in Scopus

11.

M.M. Taher, G.N. Garcia Joe

Hydroperoxide-induced diacylglycerol formation and protein kinase C activation in vascular endothelial cells

Arch Biochem Biophys, 303 (1993), pp. 260-266

ArticleDownload PDFView Record in Scopus

12.

I. Schuppe-Koistinen, P. Modéus

Thiolation of human endothelial cell glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase after hydrogen peroxide treatment

Eur J Biochem, 221 (1994), pp. 1033-1037

CrossRefView Record in Scopus

13.

H. Ishii, M.R. Jirousek, D. Koya, C. Takagi, P. Xia, A. Clermont, S.E. Bursell, T.S. Kern, L.M. Ballas, W.F. Heath, L.E. Stramm, E.P. Feener, G.L. King

Amelioration of vascular dysfunctions in diabetic rats by an oral PKC β inhibitor

Science, 272 (1996), pp. 728-731

View Record in Scopus

14.

M. Shinohara, P.J. Thornalley, I. Giardino, P. Beisswenger, S.R. Thorpe, J. Onorato, M. Brownlee

Overexpression of glyoxalase-I in bovine endothelial cells inhibits intracellular advanced glycation end product formation and prevents hyperglycemiainduced increases in macromolecular endocytosis

J Clin Invest, 101 (1998), pp. 1142-1147

CrossRefView Record in Scopus

15.

D.L. Vander Jagt, J.E. Torres, L.A. Hunsaker, L.M. Deck, R.E. Royer

Physiological substrates of human aldose and aldehyde reductases

Enzymology and Molecular Biology of Carbonyl Metabolism 6 (edited by Weiner R), Plenum Press, New York (1996)

16.

M. Brownlee

Glycation and Diabetic Complications

Diabetes, 43 (1994), pp. 836-841

CrossRefView Record in Scopus

17.

S.M. Cochrane, G.B. Robinson

In vitro glycation of glomerular basement membrane alters its permeability: a possible mechanism in diabetic complications

FEBS Lett, 375 (1995), pp. 41-44

ArticleDownload PDFCrossRefView Record in Scopus

18.

S.D. Yan, A.M. Schmidt, G.M. Anderson, J. Zhang, J. Brett, Y.S. Zou, D. Pinsky, D. Stern

Enhanced cellular oxidant stress by the interaction of advanced glycation end products with their receptors/binding proteins

J Biol Chem, 269 (1994), pp. 9889-9897

View Record in Scopus

19.

Y.M. Li, T. Mitsuhashi, D. Wojciechowicz, N. Shimizu, J. Li, A. Stitt, C. He, D. Banerjee, H. Vlassara

Molecular identity and cellular distribution of advanced glycation endproduct receptors: relationship of p60 to OST-48 and p90–80K-H membrane proteins

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 93 (1996), pp. 11047-11052

CrossRefView Record in Scopus

20.

H. Vlassara, Y.M. Li, F. Imani, D. Wojciechowicz, Z. Yang, F.T. Liu, A. Cerami

Identification of galectin-3 as a high-affinity binding protein for advanced glycation end products (AGE): a new member of the AGE-receptor complex

Mol Med, 1 (1995), pp. 634-646

View Record in Scopus

21.

N. Araki, T. Higashi, T. Mori, R. Shibayama, Y. Kawabe, T. Kodama, K. Takahashi, M. Shichiri, S. Horiuchi

Macrophage scavenger receptor mediates the endocytic uptake and degradation of advanced glycation end products of the Maillard reaction

Eur J Biochem, 230 (1995), pp. 408-415

CrossRefView Record in Scopus

22.

M. Brownlee

Advanced glycation end products in diabetic complications

Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes, 3 (1998), pp. 291-297

23.

N.B. Ruderman, J.R. Williamson, M. Brownlee

Glucose and diabetic vascular disease

FASEB J, 6 (1992), pp. 2905-2914

View Record in Scopus

24.

P. Xia, T. Inoguchi, T.S. Kern, R.L. Engerman, P.J. Oates, G.L. King

Characterization of the mechanism for the chronic activation of diacylglycerol-protein kinase C pathway in diabetes and hypergalactosemia

Diabetes, 3 (1994), pp. 1122-1129

CrossRefView Record in Scopus

25.

A. Elgawish, M. Glomb, M. Friedlander, V.M. Monnier

Involvement of hydrogen peroxide in collagen cross-linking by high glucose in vitro and in vivo

J Biol Chem, 271 (1996), pp. 12964-12972

CrossRefView Record in Scopus

26.

J. Piette, B. Piret, G. Bonizzi, S. Schoonbroodt, M.P. Merville, S. Legrand-Poels, V. Bours

Multiple redox regulation in NF-kappa B transcription factor activation

Biol Chem, 378 (1997), pp. 1237-1245

View Record in Scopus

27.

R.P. Gray, J.S. Yudkin

Cardiovascular disease in diabetic mellitus

Textbook of Diabetes (Vol 1,edited by Pickup JC, Williams G), Blackwell Science, London (1997)

28.

S.A. Krowelski, J.H. Warram

Epidemiology of late diabetic complications: A basis for the development and evaluation of prevention programs

in Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America (edited by Brownlee MB, King GL), WB Saunders, Philadelphia (1996)

29.

R. Trevison, D.J. Barnes

Pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy

Textbook of Diabetes (Vol 2, edited by Pickup JC, Williams G), Blackwell Science, Inc., London (1997)

30.

R.L. Engerman, T.S. Kern

Progression of incipient diabetic retinopathy during good glycemic control

Diabetes, 36 (1987), pp. 808-812

CrossRefView Record in Scopus

31.

Y. Wei

oxidative stress and mitochondrial DNA mutations in human aging

Soc Exp Biol Med, 217 (1998), pp. 53-63

CrossRefView Record in Scopus

32.

T. Nishikawa, D. Edelstein, X.L. Du

Normalizing mitochondrial superoxide production blocks three pathways of hyperglycaemic damage

Nature, 404 (2000), pp. 787-790

CrossRefView Record in Scopus

33.

P. Fioretto, M.W. Steffes, D.E. Sutherland, F.C. Goetz, M. Mauer

Reversal of lesions of diabetic nephropathy after pancreas transplantation

N Engl J Med, 339 (1998), pp. 69-75

CrossRefView Record in Scopus

Copyright © 2000 International Society of Nephrology. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0085253815474198

Cell Biochem Biophysics 2015 Mar;71(2):749-55. doi: 10.1007/s12013-014-0259-z.

Erythropoietin (EPO) protects against high glucose-induced apoptosis in retinal ganglional cells

The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao, 266003, China.

The aim of this study was to investigate the protective effect and mechanism of EPO on the apoptosis induced by high levels of glucose in retinal ganglial cells (RGCs). High glucose-induced apoptosis model was established in RGCs isolated from SD rats (1-3 days old) and identified with Thy1.1 mAb and MAP-2 pAb. The apoptosis was determined by Hochest assay. The levels of ROS were quantitated by staining the cells with dichloro-dihydro-fluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) and measure by flow cytometry. The SOD, GSH-Px, CAT activities, and levels of T-AOC and MDA were determined by ELISA. Change in mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) was also assessed by flow cytometry, and expressions of Bcl-2, Bax, caspase-3, caspase-9, and cytochrome C were assessed by western blotting. The RGCs treated with high glucose levels exhibited significantly increased apoptotic rate and concentrations of ROS and MDA. Pretreatment of the cells with EPO caused a significant blockade of the high glucose-induced increase in ROS and MDA levels and apoptotic rate. EPO also increased the activities of SOD, GSH-Px, and CAT, and recovered the levels of T-AOC levels. As a consequence, the mitochondrial membrane potential was improved and Cyt c release into the cytoplasm was prevented which led to significantly suppressed up-regulation of Bax reducing the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio. The expressions of caspase-3 and caspase-9 induced by high glucose exposure were also ameliorated in the RGCs treated with EPO. The protective effect of EPO against apoptosis was mediated through its antioxidant action. Thus, it blocked the generation of pro-apoptotic proteins and apoptotic degeneration of the RGCs by preventing the mitochondrial damage.《细胞生物化学与生物物理》2015年3月;71(2):749-55。doi: 10.1007 / s12013 - 014 - 0259 - z。

促红细胞生成素(EPO)保护视网膜神经节细胞免受高糖诱导的凋亡

青岛大学附属医院,山东青岛266003

本研究旨在探讨EPO对高糖诱导的视网膜神经节细胞凋亡的保护作用及其机制。以SD大鼠(1-3日龄)分离的rgc建立高糖诱导的细胞凋亡模型,用Thy1.1 mAb和MAP-2 pAb进行鉴定。Hochest法检测细胞凋亡。采用二氯-二氢荧光素二乙酸酯(DCFH-DA)染色,流式细胞仪测定活性氧(ROS)水平。ELISA法检测小鼠血清SOD、GSH-Px、CAT活性及T-AOC、MDA水平。流式细胞术检测线粒体膜电位(δψm)的变化,western blotting检测Bcl-2、Bax、caspase-3、caspase-9和细胞色素C的表达。高糖处理的RGCs凋亡率、ROS和MDA浓度显著升高。用EPO预处理细胞可显著抑制高糖诱导的ROS和MDA水平升高及凋亡率。EPO还能提高SOD、GSH-Px、CAT的活性,恢复T-AOC水平。结果改善了线粒体膜电位,阻止Cyt c释放到细胞质中,导致Bax显著抑制上调,降低Bax/Bcl-2比例。EPO处理的RGCs高糖诱导的caspase-3和caspase-9表达也有所改善。EPO对细胞凋亡的保护作用是通过抗氧化作用介导的。从而通过防止线粒体损伤,阻断促凋亡蛋白的生成和RGCs凋亡变性。Erythropoietin (EPO) protects against high glucose-induced apoptosis in retinal ganglional cells - PubMed

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25287674/

Astragalus membranaceus Injection Protects Retinal ...

https://reference.medscape.com/medline/abstract/33381196

Astragalus membranaceus Injection Protects Retinal Ganglion Cells by Regulating the Nerve Growth Factor Signaling Pathway in Experimental Rat Traumatic Optic Neuropathy. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2020; 2020:2429843 (ISSN: 1741-427X)Astragalus membranaceus Injection Protects Retinal Ganglion Cells by Regulating the Nerve Growth Factor Signaling Pathway in Experimental Rat Traumatic Optic Neuropathy.

Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2020; 2020:2429843 (ISSN: 1741-427X)

Wu Q; Gu X; Liu X; Yan X; Liao L; Zhou J

Activation of the nerve growth factor (NGF) signaling pathway is a potential method of treatment for retinal ganglion cell (RGC) loss due to traumatic optic neuropathy (TON). The present study aimed to explore the biological effects of injecting Astragalus membranaceus (A. mem) on RGCs in an experimental TON model. Adult male Wistar rats were randomly divided into three groups: sham-operated (SL), model (ML), and A. mem injection (AL). The left eyes of the rats were considered the experimental eyes, and the right eyes served as the controls. AL rats received daily intraperitoneal injections of A. mem (3 mL/kg), whereas ML and SL rats were administered the same volume of normal saline. The TON rat model was induced by optic nerve (ON) transverse quantitative traction. After two-week administration, the number of RGCs was determined using retrograde labeling with Fluoro-Gold. The protein levels of NGF, tyrosine kinase receptor A (TrkA), c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase (JNK), JNK phosphorylation (p-JNK), and nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) were assessed using western blotting. The levels of p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) and NF-κB DNA binding were examined using real-time PCR and an electrophoretic mobility shift assay. In addition, the concentrations of JNK and p-JNK were assessed using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Results. The number of RGCs in ML was found to be significantly decreased (P < 0.01) relative to both AL and SL, together with the downregulation of NGF (P < 0.01), TrkA (P < 0.05), and NF-κB (P < 0.01); upregulation of p75NTR mRNA (P < 0.01); and increased protein levels of JNK (P < 0.05) and p-JNK (P < 0.05). Treatment using A. mem injection significantly preserved the density of RGCs in rats with experimental TON and markedly upregulated the proteins of NGF (P < 0.01), TrkA (P < 0.05), and NF-κB (P < 0.01) and downregulated the mRNA level of p75NTR(P < 0.01), as well as the proteins of JNK (P < 0.05) and p-JNK (P < 0.01). Thus, A. mem injection could reduce RGC death in TON induced by ON transverse quantitative traction by stimulating the NGF signaling pathway.<i>Astragalus membranaceus</i> Injection Protects Retinal Ganglion Cells by Regulating the Nerve Growth Factor Signaling Pathway in Experimental Rat Traumatic Optic Neuropathy.

https://reference.medscape.com/medline/abstract/33381196

Glycyrrhizin Protects the Diabetic Retina against ...

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31269685

Jul 02, 2019 · Glycyrrhizin maintained normal cell numbers in the ganglion cell layer and prevented thinning of the retina at two months. These histological changes were associated with reduced reactive oxygen species, as well as reduced HMGB1, TNFα, and IL1β levels.

Cited by: 9

Publish Year: 2019

Author: Li Liu, Youde Jiang, Jena J. Steinle

Glycyrrhizin protects IGFBP-3 knockout mice from retinal ...

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1043466619302856

Jan 01, 2020 · We recently reported that glycyrrhizin, a HMGB1 inhibitor, improved retinal thickness and cell numbers in the ganglion cell layer of diabetic mice . Additionally, we have reported that IGFBP-3 regulates HMGB1 levels in retinal endothelial cells (REC) grown in high glucose [11] .

Cited by: 2

Publish Year: 2020

Author: Li Liu, Youde Jiang, Jena J. Steinle

.png)

.png)

.png)