过氧化物酶催化和氧化还原信号传导中的硫醇化学

Thiol Chemistry in Peroxidase Catalysis and Redox Signaling

抽象

描述了生物相关的硫醇和二硫化物的氧化化学。该综述着重于过氧化氢与低分子量硫醇和蛋白质硫醇的相互作用和动力学,特别是亚磺酸基团,其被认为是几种硫醇氧化过程中的关键中间体。特别地,在过氧化物酶和谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶的催化循环期间分别形成亚磺酸和亚硒酸。反过来,这些酶与硫氧还蛋白和谷胱甘肽系统紧密氧化还原通讯,硫氧还蛋白和谷胱甘肽系统是硫醇氧化还原状态的主要控制剂。细胞中形成的氧化剂来自几种不同的来源,但主要的生产者是NADPH氧化酶和线粒体。然而,这些来源产生的氧物质的不同作用是明显的,因为源自NADPH氧化酶的氧化剂主要参与信号传导过程,而线粒体产生的氧化物诱导细胞死亡,包括硫氧还蛋白系统,目前被认为是癌症化疗中硫氧还蛋白系统的重要靶标。 Antioxid。氧化还原信号。 10,1549-1564。

介绍

活性氧和氮物种(ROS和RNS)被认为是氧化应激和随之而来的生物分子损害的原因。然而,在过去几年中,相对较低浓度的氧化剂物种被认为是细胞因子和生长因子对细胞信号传导事件的第二信使(42,46,47,48,67,151, 156)。一些报道表明,许多生长因子与细胞表面的相互作用介导的细胞内ROS的增加,基本上是过氧化氢,其激活明确定义的信号传导途径。实例是肿瘤坏死因子-α(103),血小板衍生生长因子(155),表皮生长因子(7)和胰岛素(98),它们都能够诱导过氧化氢浓度的瞬时增加。在ROS介导的信号传导途径中,硫醇作为核心部分,因为它们将氧化还原状态的细胞内变化与生化过程联系起来(22,47,67,105,144)。硫醇比其他具有氧化物质的氨基酸反应更快,并且它们的一些氧化产物可以可逆地减少(22)。产生的氧化剂物质的作用可导致特定蛋白质硫醇残基的氧化或可逆的谷胱甘肽化(35,105,157)或可改变蛋白质 - 蛋白质相互作用,例如涉及氧化还原敏感性硫氧还蛋白与ASK1的相互作用(91,140,182)。 )。

图4:

由硫氧还蛋白还原酶(Thioredoxin reductase) 抑制引起的线粒体改变。在线粒体中,硫氧还蛋白还原酶的抑制改变了硫氧还蛋白氧化还原平衡,有利于氧化形式[Trx(S-S)]。氧化硫氧还蛋白通过增加线粒体膜的渗透性质而起作用,从而导致促凋亡因子的释放。

FIG. 3.

由过氧化氢介导的信号传导。由NADPH氧化酶和/或线粒体产生的过氧化氢可通过谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶的作用改变谷胱甘肽(GSH / GSSG)的氧化还原状态,进而改变谷氧还蛋白[(Grx(SH)2 / Grx(SS)]的氧化还原状态。以类似的方式,H2O2与过氧化物酶相互作用后,改变了硫氧还蛋白[Trx(SH)2 / Trx(SS)]的氧化还原平衡。过氧化氢还可以与其他酶蛋白的硫醇基团相互作用,导致形成不同的硫醇氧化还原状态的所有这些氧化还原修饰都是由敏感蛋白介导的,并导致细胞从增殖到细胞凋亡的不同后果。

硫醇和二硫化物氧化的途径

涉及蛋白质结构,酶催化和氧化还原信号传导途径的大部分生物学特性和功能取决于蛋白质和低分子量分子中存在的硫醇基团的氧化还原性质。在没有催化剂的情况下,硫醇不能进行自动氧化,但是几种游离金属离子显着提高了自动氧化的速率(70)。其他因素,例如温度,缓冲剂类型,催化剂类型和氧浓度,是重要的。然而,特别感兴趣的观察结果是自动氧化的速率取决于pH,表明硫醇盐物质参与反应(70)。在蛋白质中,众所周知,硫醇根据蛋白质结构,疏水性和电子环境呈现不同的反应性,因为变性剂通过暴露隐藏的-SH基团而增加硫醇的反应性(49)。因此,在大多数蛋白质中,可以根据它们各自的反应速率估计和分类由于局部化学微环境而具有不同反应性的硫醇群。

在生物化学中,最常见的硫醇氧化反应涉及众所周知的硫醇/二硫化物氧化还原转变(方程1):

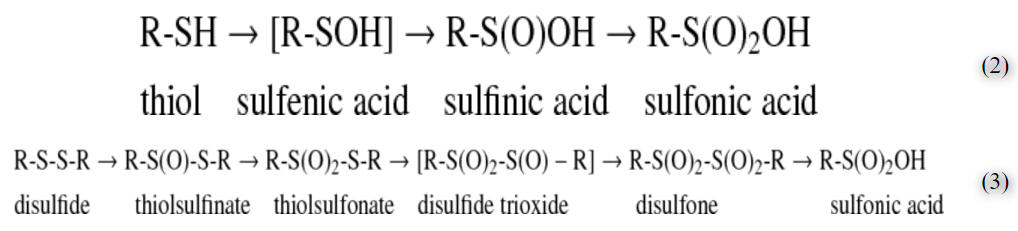

二硫化物在温和的氧化条件下形成,在生物环境中相当稳定,并且通常在细胞中不进行进一步的氧化。然而,根据所描绘的方案,硫醇和二硫化物都可以形成氧衍生物(方程2和3)

这两种途径相互连接并导致磺酸物种,作为生物系统中发现的最高氧化物质的硫。在方括号中报告的一些中间体是不稳定的。

结论

人们普遍认为,ROS不仅仅是氧化代谢的副产品,更重要的是调节细胞信号传导事件的关键因素。除了大量的实验证据之外,这种观点还得到了非吞噬细胞中公认的NADPH氧化酶的存在以及自由基如一氧化氮(Nitric oxide)起着关键作用,作为第二信使的观念的支持。

现在被认为是信号分子的过氧化氢能够与硫醇相互作用,尽管根据硫醇的类型和存在于几种酶的活性位点的微环境条件以不同的速率。特别地,过氧化物酶和GPx家族的过氧化物酶能够以非常高的速率形成亚磺酸或亚硒酸基团。细胞硫醇比其他氨基酸与氧化剂反应更快,因此是充当ROS传感器的良好候选物。此外,通过各种细胞还原系统可以容易地减少硫醇的一些氧化产物。蛋白质硫醇最相关的可逆氧化产物是二硫化物(包括与谷胱甘肽混合的二硫化物),次磺酸和亚磺酸,以及硫代亚磺酸盐。总之,硫醇氧化还原状态反映了细胞的氧化条件。它受硫氧还蛋白和谷胱甘肽系统的调节,它们分别通过过氧化还原酶和谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶与过氧化氢密切氧化还原。特别地,硫氧还蛋白的氧化还原状态将细胞氧化的程度与不同于一个细胞区室的特定生理反应联系起来。例如,硫氧还蛋白的氧化还原状态影响线粒体中的膜渗透性条件,控制胞质溶胶中的MAP激酶信号传导途径,并调节几种转录因子与细胞核中DNA的结合。根据其强度和持续时间,过氧化氢的形成可以提供从细胞增殖到细胞凋亡的完全不同的信号。诱导最后一种病症可能与抗癌治疗有关。

将巯基化学与氧化还原信号传导相关联的事件的研究是一个具有广泛兴趣和巨大扩展的研究领域。一些尚未解决的问题仍有待澄清。特别是,所涉及的氧化剂的化学性质(除过氧化氢外),其生产的大小和位置,传感器硫醇的氧化类型和程度,从氧化产物中再生天然形式等等。在,很重要。

完整阐明将氧化还原改变与细胞变化联系起来的途径可以提供从退行性疾病到癌症的大量病理生理状况的见解。此外,获得的信息将允许识别氧化还原目标以解决专门设计的药物。

Abstract

The oxidation chemistry of thiols and disulfides of biologic relevance is described. The review focuses on the interaction and kinetics of hydrogen peroxide with low-molecular-weight thiols and protein thiols and, in particular, on sulfenic acid groups, which are recognized as key intermediates in several thiol oxidation processes. In particular, sulfenic and selenenic acids are formed during the catalytic cycle of peroxiredoxins and glutathione peroxidases, respectively. In turn, these enzymes are in close redox communication with the thioredoxin and glutathione systems, which are the major controllers of the thiol redox state. Oxidants formed in the cell originate from several different sources, but the major producers are NADPH oxidases and mitochondria. However, a different role of the oxygen species produced by these sources is apparent as oxidants derived from NADPH oxidase are involved mainly in signaling processes, whereas those produced by mitochondria induce cell death in pathways including also the thioredoxin system, presently considered an important target for cancer chemotherapy. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 10, 1549–1564.

Introduction

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS) are deemed responsible for oxidative stress and the consequent damage occurring to biologic molecules. However, in the last few years, oxidant species, at relatively low concentrations, have been considered to act as second messengers in the cell-signaling events in response to cytokines and growth factors (42, 46, 47, 48, 67, 151, 156). Several reports indicate that the interaction of a number of growth factors with the cell surface mediates an intracellular increase of ROS, essentially hydrogen peroxide, which activates well-defined signaling pathways. Examples are tumor necrosis factor-α (103), platelet-derived growth factor (155), epidermal growth factor (7), and insulin (98), which are all able to induce a transient increase in hydrogen peroxide concentration. In the ROS-mediated signaling pathways, thiols play a central part as they couple the intracellular changes in redox state to the biochemical processes (22, 47, 67, 105, 144). Thiols react faster than the other amino acids with oxidizing species, and some of their oxidation products can be reversibly reduced (22). The action of the oxidant species produced can lead to oxidation or reversible glutathionylation of specific protein thiol residues (35, 105, 157) or can alter protein–protein interaction such as that involving the redox-sensitive thioredoxin with ASK1 (91, 140, 182).

Pathways of Thiol and Disulfide Oxidation

A large part of biologic properties and functions involving protein structure, enzyme catalysis, and redox-signaling pathways depends on the redox properties of the thiol group present both in protein and in low-molecular-weight molecules. Thiols are unable to undergo autoxidation in the absence of a catalyst, but several free metal ions markedly increase the rate of autoxidation (70). Other factors, such as temperature, type of buffer, type of catalyst, and oxygen concentration, are important. However, an observation of particular interest is that the rate of autoxidation depends on pH, indicating the participation of the thiolate species in the reaction (70). In proteins, it is well known that thiols present different reactivities according to the protein structure, hydrophobicity, and the electronic environment, as denaturing agents increase the reactivity of thiols by exposing hidden —SH groups (49). Consequently, in most proteins, populations of thiols of different reactivities due to the local chemical microenvironment can be estimated and classified according to their respective reaction rates.

In biochemistry, the most familiar oxidation reaction of thiols involves the well-known thiol/disulfide redox transition (Eq. 1):

Disulfides are formed under mild oxidizing conditions, are rather stable in a biologic milieu, and usually, in the cell, do not proceed to further oxidation. However, both thiols and disulfides can form oxygen derivatives according to the scheme depicted (Eqs. 2 and 3)

Both pathways are interconnected and lead to the sulfonic species, as the highest oxidized species of sulfur found in biologic systems. Some intermediates, reported in square brackets, are unstable.

Sulfenic acid

Sulfenic acid (R-SOH) is the first member of sulfur oxyacids and, although unstable and highly reactive, has gained growing interest in biologic systems, particularly with reference to redox signaling (120). Because of their instability, sulfenic acids are essentially viewed as reaction intermediates, and only very few sulfenic acids have been isolated and crystallized (63, 75, 143). However, in some proteins, sulfenic acids can find proper stabilizing conditions, and sulfenic derivatives have indeed been described (28). According to Liu (93), the stability of the —SOH residue in proteins, in addition to hydrogen bonding, depends on its location in an apolar microenvironment that limits solvent access. Probably the most important factor in stabilizing sulfenic acids in proteins is the absence of proximal thiol groups or other nucleophiles. For instance, a thiol group would rapidly interact with the sulfenic moiety, forming a disulfide (2) (Eq. 6).

Sulfenic acids are formed after reaction of the thiolate group with hydrogen peroxide (vide infra, Eq. 10), and other hydroperoxides such as alkylhydroperoxides and peroxynitrite (120). Sulfenic acids also originate from hydrolysis of S-nitrosothiols (Eq. 4) and after reaction of thiols with thiolsulfinates (Eq. 5):

Sulfenic acids can undergo both electrophilic and nucleophilic reactions, according to different reaction conditions (2). For instance, sulfenic acids are reactive toward nucleophilic reagents such as dimedone (5,5′-dimethyl-1,3-cyclo-hexanedienone) or TNB− (2-nitro-5-thiobenzoate anion, derived from the reduction of the thiol reagent DTNB [5,5′-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid)]. Sulfenic acids also react with electrophilic molecules such as NBD chloride (7-chloro-4-nitrobenzo-2-oxa-1,3-diazole), which leads to a sulfoxide, although a sulfenate ester, formed directly or after tautomerization, can also be considered (119). Dimedone, TNB−, and NBD-Cl are used to identify cysteine sulfenic acids in proteins (2, 37, 41, 119, 171).

A most significant reaction of sulfenic acids is their interaction with thiols forming disulfides (Eq. 6):

This reaction is particularly relevant in enzymes involved in redox signaling, as the reaction of sulfenic acid residues with glutathione, present in high concentrations in cells, and the consequent formation of a mixed disulfide, leads to the glutathionylation of specific proteins (Eq. 7):

The formation of mixed disulfides, together with that of sulfenamides (141, 164) (Eq. 8) prevents overoxidation of the cysteine residues to sulfinic and sulfonic acids (vide infra):

Nonetheless, the rate of formation of sulfenic acid from many thiolates via reaction with hydrogen peroxide (as is the case with PTP1B, the subject of the two in vitro studies quoted earlier) is too slow to happen in vivo; and even if it did form, the presence of millimolar GSH in cells would convert the sulfenic acid or subsequently formed sulfenamide of PTP1B to the protein-S-S-G form very rapidly (48).

Sulfenic acids can easily self-condense to form a thiolsulfinate (27, 74, 158) (Eq. 9):

The facile dehydration reaction of sulfenic acids proceeds through the formation of a dimer in which the two sulfenic acids are hydrogen-bonded, and involves a nucleophilic attack exerted by the sulfenic acid sulfur on the sulfur of the second sulfenic acid molecule (27, 63, 75) (Fig. 1). This reaction is a clear example of both the nucleophilic and electrophilic character of these acids.

FIG. 1.

Self-condensation of two sulfenic acid molecules forming a thiolsulfinate.

Reactions of thiols with hydrogen peroxide

This reaction is of particular relevance for biologic systems. The oxidation of thiols by hydrogen peroxide in the absence of metal catalysis has been known for a long time (116). Little and O'Brien (90) studied the inactivation of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase by peroxide and concluded that H2O2 treatment did not involve disulfide formation, but, instead, the thiol was oxidized to a sulfenic acid residue. The reaction was pH dependent, indicating the involvement of a thiolate group acting as a nucleophile on hydrogen peroxide, according to Eq. 10:

The peroxide-inactivated enzyme can be reactivated if quickly treated with an excess of low-molecular-weight thiols. However, when the treatment is delayed, the inhibition becomes irreversible, indicating that the sulfenic residue undergoes further oxidation to sulfonic acid (90). In an examination of the kinetics of this reaction, it was observed that the reaction of H2O2 with low-molecular-weight thiols (glutathione, cysteine, cysteamine, penicillamine, N-acetylcysteine, dithiothreitol, and captopril) is rather slow and falls in the range of 18–26 M−1 s−1, making this event scarcely significant in a biologic context (172). With H2O2, proteins containing low pKa thiols show a 20- to 30-fold increase in rate constant (172) that, however, is still largely insufficient to compete with enzymatic processes such as those of glutathione peroxidases and peroxiredoxins, which are orders of magnitude more efficient in reducing hydrogen peroxide (26, 43, 73). This indicates that ionization of the thiol group alone is not sufficient to bring the interaction of hydrogen peroxide in proteins to a level comparable to that of thiol or selenium peroxidases. For instance, PTP1B (protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B) reacts with hydrogen peroxide at a rate similar to that of low-molecular-weight thiols (151, 152, 172). Thus, the demonstration that an intermediate sulfenic acid can be formed by reaction of purified PTP1B with H2O2 in vitro (141, 164) might be scarcely relevant in a physiologic context (48). A comparison of the second-order rate constants of various proteins with hydrogen peroxide (152) indicates that, among enzymes bearing thiolate moieties, only peroxidases and the bacterial sensor OxyR exhibit rate constants on the order of 105–106 M−1 s−1, whereas phosphatases and other enzymes such as glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and papain are in the range of 10–102 M−1 s−1. Therefore, to react rapidly with hydrogen peroxide, the low pKa of cysteine is not a sufficient condition, but the thiolate requires a proper environment defined by specific amino acid residues able to stabilize the transition-state intermediate (159).

Sulfinic and sulfonic acids

Sulfinic acids, together with disulfides and sulfonic acids, are stable oxidation products and can be isolated and crystallized. Sulfinic acids easily oxidize to the corresponding sulfonic acids and can also be formed enzymatically. For instance, the sulfinic acid hypotaurine is formed by the action of the enzyme cysteamine oxygenase on the thiol cysteamine.

Protein sulfinic acid formation has gained relevance in the redox control of peroxiredoxins (124, 174, 177). These enzymes decompose hydrogen peroxide and present two redox-active cysteines (a peroxidatic and a resolving cysteine) at their catalytic site. On interaction with H2O2, the peroxidatic cysteine is oxidized to sulfenic acid, and the active-site helix locally unfolds to permit the formation of a disulfide mediated by the resolving cysteine. However, when hydrogen peroxide concentration increases, the sulfenic acid intermediate can interact with another molecule of hydrogen peroxide, leading to the formation of a sulfinic acid [Eq. 11 (Sp, sulfur of the peroxidatic cysteine)] that constitutes an overoxidized and inactive form of the enzyme (124, 174, 177):

According to the floodgate model (174), peroxiredoxins are able to regulate redox signaling by maintaining low resting levels of hydrogen peroxide and permitting increased levels during signal transduction (174). Although cysteine sulfinic acid cannot be reduced back to thiol by the major cell reductants, such as glutathione, thioredoxin, or ascorbic acid (69), a highly selective enzyme, sulfiredoxin, is able to reverse the inactivation of peroxiredoxin via the formation of cysteine sulfinic acid (13, 173). The reaction requires ATP and forms a sulfinic phosphoryl ester of peroxiredoxin that is further converted to a thiolsulfinate by thiols such as glutathione or thioredoxin (69). In addition to sulfiredoxin, sestrins, a family of proteins whose expression is modulated by p53, act as ATP-dependent sulfinyl reductases catalyzing the regeneration of peroxiredoxins (18). The problem with the floodgate model is that it assumes that H2O2 has to overcome its elimination to produce signaling. In actuality, however, a second messenger acts locally where it is produced, and competition occurs between its target effector and the enzymes that eliminate it. For example, protein kinase A and phosphodiesterase compete for cyclic AMP. The idea that H2O2 has to overwhelm peroxiredoxins to effect signaling is as unlikely as proposing that phosphodiesterases would have to be overwhelmed by cyclic AMP for protein kinase A to be activated. Indeed, the oxidation of thioredoxin by a peroxiredoxin is itself a signaling event (91).

Furthermore, according to Stone (152), the apparent second-order rate constant of the inactivation of the peroxiredoxin is relatively low and in the same range of protein tyrosine phosphatases, suggesting that overoxidation of peroxiredoxins in not the unique way to sense low levels of hydrogen peroxide by these enzymes.

Sulfonic acids are the highest oxidized species of thiols and disulfides. Chemically, they are obtained with strong oxidizing agents but are also found to occur naturally as taurine, isethionic acid, and methanesulfonic acid (70).

Oxidation of disulfides

Oxidation of disulfides is generally favored by anhydrous conditions and finally results in the formation of sulfonic acids after scission of the S-S bond (143). Thiolsulfinates (disulfide monoxides) are the first members of the disulfide oxidation products. They occur naturally in biologic systems such as the well-known component of garlic, allicin (diallyl disulfide monoxide), and exhibit antibacterial and fungicidal properties (143). They can be easily reduced to the corresponding disulfides by thiols with the intermediate formation of sulfenic acids (70, 143), hence revealing their importance in the biologic redox processes. On storage, they readily disproportionate to disulfides and thiolsulfonates (143).

Thiolsulfonates were the first products to be obtained from the oxidation of disulfides (143). In the presence of water, they hydrolize to the corresponding sulfinic acids and disulfides, so they can be described as sulfenyl sulfinates. Similarly, their reaction with thiols leads to sulfinic acid and disulfides. Thiolsulfonates are endowed with antimicrobial properties and also act as protectants against ionizing radiation (168). Alkylthiolsulfonates, such as methyl methane thiolsulfonate, have been used as thiol-modifying reagents for temporary blocking of accessible —SH groups of proteins. Thiolsulfonates are highly specific for thiol groups and react vey rapidly in a reaction that goes to completion even in the presence of nearly equimolar concentrations of thiols and alkylthiolsulfonates (147, 175). More recently, glycosyl-phenylthiosulfonates were used for the pseudo-glycosylation of proteins due to reaction with cysteine residues (50).

Oxidation of thiols by radiation and thiyl radical formation

Thiols can be oxidized by radiation of different energies such as x-, β-, and γ-rays and UV light. Both disulfides and higher oxidation states of sulfur are formed either directly or through the radiolysis or photolysis of water. Reactions proceed through the formation of a thiyl radical (Eq. 12), which, in addition to dimerization to a disulfide (Eq. 13), can interact with oxygen, forming a thioperoxyl radical intermediate (70, 167) (Eq. 14):

Thiyl radicals can also be formed by transition metal-catalyzed oxidation of thiols or by the action of peroxidases (horseradish peroxidase, myeloperoxidase, lactoperoxidase, etc.) or myoglobin in the presence of hydrogen peroxide (32). Thioperoxyl radicals can interact with the parent thiols, leading to the formation of sulfenic acid (167) and regeneration of the thiyl radical (Eqs. 15 and 16):

A well established reaction of the thiyl radical is its interaction with the thiolate anion, forming first the strong reductant disulfide radical anion, which, in turn, forms superoxide anion on reaction with oxygen (167), according to Eqs. 17 and 18:

Oxidation of thiols by nitric oxide derivatives

Nitric oxide (·NO) is an important second messenger that, among other functions, can elicit smooth muscle relaxation through the activation of the soluble form of the enzyme guanylate cyclase (sGC). This enzyme catalyzes the cyclization of guanosine triphosphate (GTP) to cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). Because of the importance of cGMP in a variety of signaling events (i.e., cGMP-dependent kinases, ion channel activity), the activity of sGC is an important aspect of fundamental cell signaling. Nitric oxide activates sGC by binding to the ferrous form of a regulatory heme group on the enzyme, leading to a dramatic increase in the rate of formation of cyclic GMP. Recently, it was proposed that this model for sGC activation by NO may be overly simplistic and may involve other NO binding sites as well (24). However, this idea has been challenged (138). Regardless, the NO-sGC-cGMP pathway is the most-established and generally accepted aspect of NO-mediated signaling.

However, other mechanistically distinct pathways of NO-mediated signaling have been proposed. The formation of nitrosothiol (RSNO) from protein cysteine may also be an important component of signaling by NO (60, 100). RSNO is formed in a number of signaling proteins, but we do not know how RSNO is formed in vivo. A reaction of NO with RSH or RS− would not directly yield RSNO, but rather would give an intermediate thionitroxide (RSNHO·), if it happened at all (183). Although thionitroxides are generally thought to be relatively unstable, some proteins may have the appropriate stabilizing structural motif allowing their formation in some biologic circumstances (183). Generation of RSNO via intermediary thionitroxides would require an additional one-electron oxidation, and this has been proposed as a possible mechanism of RSNO generation, whereby the oxidation is carried out by dioxygen (55). However, this mechanism for the generation of RSNOs is not generally established. A number of other reactions that can be demonstrated to occur in vitro for generating RSNO have been proposed to be biologically relevant.

Nitric oxide can react with dioxygen to form nitrogen dioxide (·NO2) (Eq. 19):

Although NO is not an oxidant under biologic conditions, NO2 is a reasonable one-electron oxidant capable of reacting with biologic thiols (Eq. 20) to generate the thiyl radical (RS·) (44):

Further reaction of the thiyl radical with NO can then generate RSNO (Eq. 21):

It must be mentioned that the generation of NO2 via reaction 19 requires significant levels of NO, because the reaction kinetics are second order in NO. Thus, only at high concentrations of NO can this chemistry be biologically relevant. Significantly, both NO and O2 will favorably partition into lipophilic compartments in cells, predicting that direct and indirect NO2 chemistry (vide infra) may be most relevant in these compartments (94).

Besides acting as a direct thiol oxidant, NO2 can also react with NO to give N2O3, an electrophilic species capable of nitrosating thiols (Eqs. 22 and 23):

However, under biologic conditions, the relevance of thiol nitrosation via N2O3 as a mechanism of RSNO generation is questionable, because NO2 will likely react with other biologic species (e.g., GSH) long before it will react with NO (44, vide supra). However, as mentioned earlier, in or near hydrophobic environments of the cell (i.e., membranes or hydrophobic domains in proteins), this chemistry may be relevant, because concentrations of the reactants (NO and O2) will be higher, and other potential NO2-scavenging species may not be present.

It is becoming increasingly evident that the thiyl radical is a part of the catalytic cycle of many enzymes (153). Thus, another possible mechanism for the generation of RSNO in biologic systems involves the reaction of NO with an RS· present during enzyme catalysis, such as during the catalytic process of ribonucleotide reductases in which a thiyl radical is produced in the active site (78). Such an intermediate is a possible target for the direct reaction with nitric oxide, yielding RSNO, as shown earlier.

A distinct mechanism for the generation of RSNO involves coordination of NO to a ferric iron-heme and subsequent reaction with a thiol in a process called reductive nitrosylation (89) (Eqs. 24 and 25). This reaction is first order in NO and therefore does not have the kinetic restriction on biologic relevance mentioned earlier.

Metalloproteins also can participate in another reaction that can lead to the generation of an RSNO species. Oxidation of nitrite (NO2−) by hydrogen peroxide via peroxidases (i.e., myeloperoxidase) can generate NO2 (19) (Eq. 26), a species already discussed as a potential reactant in the generation of RSNOs.

The formation of RSNO is often called S-nitrosylation, although that does denote a precise chemical mechanism in the manner that phosphorylation or acetylation does. Nonetheless, as many signaling processes end with the “ylation” suffix, S-nitrosylation has become the commonly used term.

Control of Cell Thiol Redox State by Thioredoxin and Glutathione Systems

The thiol redox control concept was introduced to indicate the signaling action of the thioredoxin system on the thiol enzyme activity (65, 66). The cellular thiol redox state is controlled by two major systems, the thioredoxin and glutathione systems, which are in a close redox communication with hydrogen peroxide through peroxiredoxins and glutathione peroxidases, respectively (Fig. 2). They are present both in the cytosol and mitochondria and, in either system, the reducing equivalents are fed by NADPH. Different pathways of NADP+ reduction are operative in the cytosol versus mitochondria. Whereas cytosolic NADP+ is reduced in the pentose phosphate pathway, in mitochondria, electrons are delivered through the various dehydrogenases coupled to the energy-linked transhydrogenase that catalyzes the transfer of reducing equivalents from NADH to NADP+. Furthermore, the mitochondrial glutamate and isocitrate dehydrogenases, in addition to NAD+, use NADP+ for the oxidation of their respective substrates, providing a further source of NADPH.

FIG. 2.

Reduction of hydrogen peroxide mediated by thioredoxin (A) and glutathione (B) pathways. Electrons are delivered by NADPH maintained reduced by the pentose phosphate pathway in the cytosol, and by the respiratory substrates in mitochondria. The proton-translocating transhydrogenase transfers electrons from NADH to NADP+ to form NADPH. Sulfenic and selenenic acid residues appear as key intermediates in the thioredoxin and glutathione pathways, respectively.

Thioredoxin system

The thioredoxin system includes thioredoxin reductases (TrxR) and thioredoxins (Trx), which act sequentially in transferring electrons delivered by NADPH. Thioredoxin reductases are homodimers present in the cytosol, nucleus (TrxR1) (54, 184), and mitochondria (TrxR2) (84, 133). Thioredoxins also are present both in the cytosol (Trx1) and mitochondria (Trx2), and the cytosolic isoform can also enter the nucleus. The thioredoxin system has a crucial role in regulating functions such as cell viability and proliferation via a thiol redox state (5, 87, 122). Thioredoxins act as electron donors for a number of enzymes, such as ribonucleotide reductase (83), methionine sulfoxide reductase (85), and peroxiredoxins (62, 130). The latter may be active as antioxidants by rapidly regulating the level of hydrogen peroxide (130) but, depending on the conditions, may also influence the redox state of thioredoxins that can exert a central role in the redox regulation of signaling molecules and transcription factors. This role, mediating the cellular response to changes in the redox state, is further complemented by glutaredoxins (87) (vide infra). Thioredoxin-1, in its reduced form, binds to ASK1 and inhibits its activity, acting therefore as a negative effector of apoptosis. However, because this inhibition is removed after oxidation of thioredoxin, which dissociates from ASK1 (140), it is clearly apparent that thioredoxin acts as a redox sensor of ASK1. Recently, endogenous generation of H2O2 by stimulation of Nox2 in alveolar macrophages was shown to activate ASK1 through the oxidation of thioredoxin-1 (91).

Several transcription factors depend on redox-sensitive cysteines, and their function is modulated by the redox state of thioredoxin, which, in turn, reflects the cellular redox state. The activity of the transcription factor NF-κB is inhibited in the cytosol by reduced thioredoxin. In contrast, reduced thioredoxin activates this transcription factor in the nucleus by promoting its binding to DNA (72, 102). Other transcription factors, sensitive to thioredoxin, are the tumor-suppressor p53 (161), the hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) (169), the glucocorticoid receptor (99), and the AP-1 protein complex (61). The latter is activated by the direct association of Trx with redox factor-1 (Ref-1) (61). Redox factor-1 is a nuclear 37-kDa enzyme (176) that, in addition to a DNA-repair function, possess two redox-sensitive cysteines at positions 63 and 95 (166). Ref-1, by reducing critical cysteines, also facilitates the binding to DNA of several transcription factors, including NF-κB, p53, and HIF-1α (106). Ref-1 deficiency renders cells more sensitive to apoptosis, as shown by its knockdown by small interfering RNA (siRNA) (178). Thioredoxin strictly cooperates with Ref-1 as phorbol esters treatment of COS-7 cells stimulates the translocation to the nucleus of thioredoxin, which, in turn, potentiates AP-1 activity (61).

The Nrf2-Keap1 system is recognized as a major cell-defense mechanism against oxidative stress and xenobiotics and plays a key role in upregulating phase 2 enzymes. In cytoplasm, the transcription factor Nrf2 is associated with a specific repressor protein, Keap1, that inhibits its translocation to the nucleus (165) but also acts as a participant in causing the rapid turnover of Nrf2 by ubiquitination and degradation (180). Keap-1 is a redox-sensitive protein with several cysteines. Some of them (Cys273 and Cys288) act as “reactive cysteines” and, on interaction with ROS or electrophiles, undergo oxidation or covalent modification, thereby facilitating the dissociation of the Nrf2-Keap1 (165). Consequently, Nrf2 can translocate to the nucleus, where it accelerates the transcription of phase 2 genes, including thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase genes (14, 77). The role of Trx in cell growth and development, its antioxidant action, and thiol redox regulation of transcription factors provides a rationale for the observed upregulation of thioredoxin in several types of cancers (11, 51, 109). Association of this upregulation with resistance to apoptosis (56) makes Trx, together with TrxR, a relevant target for antitumor therapy.

Glutathione system

Glutathione is the predominant nonprotein thiol in cells where it plays essential roles as an enzyme substrate and a protecting agent against xenobiotic compounds and oxidants (38). Glutathione, maintained in the reduced state by glutathione reductase, is able to transfer its reducing equivalents to several enzymes, such as glutathione peroxidases (GPx), glutathione transferases (GSTs), and glutaredoxins. The latter, similar to thioredoxin, can interact with ribonucleotide reductase and with several other proteins involved in cellular signaling and transcription control, such as NF-κB, PTP-1B, PKA, PKC, Akt, and ASK1 (97). Mammalian cells contain a cytosolic (Grx1) and a mitochondrial (Grx2) glutaredoxin. Mitochondria contain a second glutaredoxin (Grx5), which is homologous to yeast Grx5 in bearing a single cysteine residue at its active site.

It is a rather old concept that formation of mixed disulfides between protein cysteine residues and glutathione constitutes a protective mechanism for thiols, which prevents their further oxidation in addition to possible roles in cell signaling. Mixed disulfides are derived from the reaction of sulfenic acids in proteins and glutathione rather than from direct interaction of glutathione disulfide and protein thiols. Glutaredoxins play a critical role in the reversible formation of protein mixed disulfides, as they are able to catalyze both the reduction and the formation of mixed disulfides from protein thiols and reduced glutathione (10, 12). Hence, they may act as sensors of the glutathione redox state.

Several systems are sensitive to glutathionylation (12), including mitochondrial complex I (10), which, in this way, increases the production of the superoxide anion (157). According to Johansson et al. (71), mitochondrial glutaredoxin is reduced also by thioredoxin reductase, demonstrating that glutathione and thioredoxin pathways are linked. Glutaredoxin is overexpressed in cancer cells (104, 108) and protects from apoptosis (34), while silencing the expression of Grx2 by RNAi sensitize cells to apoptosis-inducing agents (88).

Thioredoxin, glutaredoxin, and Ref-1 favor the DNA binding of several transcription factors by maintaining crucial cysteines in a reduced state (106). Although thioredoxin and glutathione systems are apparently similar in their cellular functions as they maintain a reduced environment by using the same source of reducing equivalents (NADPH), a major difference is represented by the cell concentrations of glutathione that are far larger than that of thioredoxin (64). Nevertheless, the two systems operate independently, fulfilling different roles within the cell (117, 160). The presence in the cell of different proteins exhibiting the thioredoxin fold underlines their specific multiple signaling role (117).

Sulfenic and selenenic acid residues as key intermediates in thioredoxin and glutathione pathways

It is worth mentioning that components of the thioredoxin and glutathione systems contain residues of selenocysteine at their active sites, such as in glutathione peroxidases (15) and cytosolic and mitochondrial thioredoxin reductases (54, 107, 148, 154). The thioredoxin system reduces hydrogen peroxide by means of peroxiredoxins, in which a sulfenic acid constitutes an important intermediate formed after a rapid reaction between the active-site cysteine in its thiolate (R-S−) form and hydrogen peroxide. As mentioned previously, this chemistry must be aided by other residues in the active site as a change in the pKa of the cysteine alone would not account for a rate constant 105- to 106-fold more rapid than the reaction of low-molecular-weight thiols with H2O2. Similarly, in the glutathione pathway, a selenenic acid is formed at the active site of most glutathione peroxidases. Formation of the selenenic acid via reaction of the selenolate (the selenium equivalent of a thiolate) with hydrogen peroxide represents one of the fastest reactions of a peroxidase with hydrogen peroxide with a second-order rate constant of 6 × 107 M−1s−1 (43). Selenocysteines are similar to the reactive cysteines, having a low pKa, and consequently are ionized at physiologic pH (148). As in cysteine-based catalysis, the low pKa of selenocysteines is not sufficient for a rapid reaction with H2O2, and a well-defined aminoacid environment is needed to stabilize the reaction intermediate.

Cell Production of Oxidant Species

In the cell, the oxidants interacting with reactive thiols and selenols are produced from several different sources. Recognized generators of hydrogen peroxide are xanthine oxidase (30), lipoxygenases (111), or γ-glutamiltransferase (114), as well as cytochromes P450 and b5 (30). However, the most relevant producers of oxidants are NADPH oxidases and mitochondria (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Signaling mediated by hydrogen peroxide. Hydrogen peroxide, produced by NADPH oxidase and/or mitochondria, can alter the redox state of glutathione (GSH/GSSG) and, in turn, of glutaredoxin [(Grx(SH)2/Grx(SS)] through the action of glutathione peroxidases. In a similar way, H2O2, after interaction with peroxiredoxins, modifies the redox balance of thioredoxin [Trx(SH)2/Trx(SS)]. Hydrogen peroxide can also interact with thiol groups of other enzymatic proteins leading to the formation of different oxidation states of sulfur. All these redox modifications of thiol redox state are mediated by sensitive proteins and lead to different consequences for the cell, going from proliferation to apoptosis.

NADPH oxidases

Phagocytic cells such as neutrophils and macrophages are endowed with a NADPH oxidase responsible for the “respiratory burst,” an oxygen-consuming process that results in the formation of reactive oxygen species that promote host defense against invading microorganisms (31, 81). Phagocytic NADPH oxidase is a multienzyme complex constituted by a catalytic subunit, gp91phox (Nox2) that, along with the p22phox subunit, forms a membrane-associated heterodimer (flavocytochrome b588) (31, 80, 81). Nox2 contains a flavin adenine nucleotide (FAD) and the NADPH-binding site located on the cytosolic side. In the transmembrane helices of the enzyme, two hemes are present and transfer the electrons from cytosolic NADPH, through FAD, to oxygen, which is reduced to superoxide in a rapid outer-sphere reaction (68). Cytosolic regulatory subunits such as p47phox, p67phox, and the small GTPase Rac1 or Rac2 are necessary to activate the electron-transfer reaction within the NADPH oxidase complex (80).

Several homologues of gp91phox (Nox1, Nox3, Nox4, Nox5) have been found in a variety of tissues, indicating that NADPH oxidase activity is present also in nonphagocytic cells (52, 80). Other nonphagocytic oxidases are the dual oxidases Duox1 and Duox2, found in the thyroid gland and first indicated as thyroid oxidases and involved in thyroxine synthesis. However, they can also be found in nonthyroid tissues (52). Dual oxidases, in addition to the oxidase portion, bear a peroxidase-like domain and two EF-hand motifs (52). The nonphagocytic oxidases rely on regulatory subunits for their functioning. In addition, Nox5 and Duox1/2 are activated by calcium ions.

The ability of NADPH oxidase to produce reactive oxygen species in a regulated manner has for long been considered a unique feature of phagocytic cells. This function is linked to the defense against invading microorganisms, and the dysregulation of this system has been associated with a number of chronic inflammatory diseases (163). However, the existence of several homologues of the phagocyte enzyme in many different aerobic organisms indicated that NADPH oxidases are involved in a range of different functions, such as cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, and survival (9, 81). Heme peroxidases are well-defined targets of ROS produced by Nox2. This is apparent in phagocytes, where H2O2 interacts with myeloperoxidase or eosinophil peroxidases, generating secondary oxidants (163). In the thyroid gland, a similar cooperative interaction between Duox1/2 and a locally produced heme peroxidase (thyroperoxidase) also occurs and promotes the synthesis of the thyroid hormone (36, 146). However, in contrast to Nox2 (and Duox1/2), the other Nox isoforms appear not to be functionally linked to locally produced heme peroxidases, and other targets, such as protein cysteine residues, appear to be involved (163). Plasma membrane NADPH oxidases constitute the primary sources of reactive oxygen species implicated in the receptor-dependent signaling cascade and involve growth factors and cytokines such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), and insulin (132, 142). Although the coupling of receptor activation to NADPH oxidase in nonphagocytic cells is still not completely clarified (132), the activation of phosphoinositol 3-kinase appears to play a role (129). Activated phosphoinositol 3-kinase stimulates the production of phosphatidylinositol trisphosphate, resulting in the activation of Rac1, which, in turn, stimulates NADPH oxidase to produce reactive oxygen species (129). Increased concentration of hydrogen peroxide causes oxidation of thiols, as occurs at the level of protein tyrosine phosphatases, which possess a conserved catalytic cysteine residue of low pKa (132, 155). Nox activation can also regulate Ca2+-dependent signaling through oxidation of cysteines of the Ca2+ channel (4, 163).

NADPH oxidase is a finely tuned and tightly regulated multienzyme complex that rapidly generates relatively low concentrations of hydrogen peroxide, which, in turn, can also be easily degraded (142). This efficient kinetics of activation/inactivation is a fundamental feature for systems acting in signal-transduction pathways where activation occurs in a time scale of minutes (142). However, dysregulation of this system or overexpression of NADPH oxidases can lead to proinflammatory or cytotoxic conditions associated with acute and chronic diseases (82). In endothelial cells, it has been observed that dietary flavonoids and their metabolites can target NADPH oxidase (149), reducing superoxide production and hence leading to an increase in the steady-state level of nitric oxide by suppressing superoxide-mediated loss of NO (150).

Mitochondria

Mitochondria display different roles in metabolism as, in addition to their well-known bioenergetic functions, they are also able to control the fluxes of cellular calcium (17, 59), to induce apoptosis by releasing proapoptotic factors (79), and to produce reactive oxygen species (20, 45, 95, 96, 126). Formation of superoxide by mitochondria was first observed many decades ago (45, 95) and has generated a large scientific interest whose description is beyond the scope of this review. Mitochondria are considered the major source of ROS of the cell. Superoxide anion is formed first by the autoxidation of the respiratory chain and is rapidly dismuted by the manganese superoxide dismutase to hydrogen peroxide, which can freely diffuse through the mitochondrial membranes into the cytosol. The statement that ROS formation corresponds to ∼3% of all oxygen consumed is considered an overestimate of at least one order of magnitude (1, 17). According to Giorgio et al. (53) mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide formation is not simply an accidental by-product of the aerobic metabolism but can be produced through a specialized enzyme (p66Shc) able to take up electrons from reduced cytochrome c.

The mitochondrial glutathione and thioredoxin systems appear mostly devoted to the removal of hydrogen peroxide, largely produced by this organelle. In mitochondria, several sources of ROS production exist, whereas different systems operate in removing reactive oxygen species and particularly hydrogen peroxide. Consequently, a steady state between production and consumption of hydrogen peroxide sets up (3, 134, 185). This steady state might be altered by either an increased production of ROS by the respiratory chain or by a decreased removal, such as that occurring after inhibition of thioredoxin or glutathione systems. The net amount of hydrogen peroxide released outside mitochondria derives from the difference between H2O2 production and removal.

Different roles exerted in cell signaling by oxidants produced by different sources

ROS produced by different sources in different compartments of the cell give different signaling responses (Fig. 3). In addition, their local concentration and persistence over time are critical factors. The mitochondrial rate of ROS production is generally regarded to exceed the scavenging capacity, therefore eliciting a continuous release of oxidants that are potentially involved in the pathogenesis of both degenerative diseases and aging. However, in addition to a solely harmful action, mitochondrially produced ROS are considered to play a role in signaling (16, 21, 33, 42, 76, 110, 128, 170, 181), although mitochondrial ROS formation appears to be not as well regulated as that of NADPH oxidases (39, 181). Moreover, several factors that stimulate the mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species potentially lead to cell-growth arrest or to cell death by apoptosis or necrosis (86, 113, 127). Other examples are glutamate (40), ceramide (123), and TNF-α (145). In addition, inhibitors of the respiratory chain inducing a large production of ROS cause cell death (112). Consequently, the sustained mitochondrial production of ROS appears more involved in apoptosis or cell-cycle arrest or both than in cell proliferation. Conversely, NADPH oxidases, which elicit an early and short-lived production of ROS, result essentially in a proliferation signal. Although the cell environment is very complex and a single specific stimulus can give different and even opposite responses, the roles of mitochondria and NADPH oxidases in producing hydrogen peroxide must be recognized as being potentially distinct (113). However, a cross-interaction between the two pathways might also occur. As mentioned earlier, the production of mitochondrial ROS depends not only on the inhibition of the respiratory chain but also on the balance between production and consumption. Therefore, mitochondria fulfil an important role in cell apoptosis, not only because of the release of proapoptotic factors but also as producers of a sustained and long-lasting ROS concentration.

Cell death induced by inhibition of the thioredoxin system

Recently, several observations indicate that the thioredoxin system has a relevant role in cancer. A large interest exists in considering thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase important targets for cancer chemotherapy (6, 8, 25, 58, 118, 121, 162), essentially on the assumption that many malignant cells overexpress both thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase. A direct demonstration that thioredoxin reductase could be a primary target for cancer therapy was obtained by transfecting lung cancer cells with siRNA specifically targeted to TrxR1 (179). These cancer cells were able to reverse their morphology and anchorage-independent growth properties, becoming similar to normal cells (179). Metal complexes, and in particular gold(I) and gold(III) complexes, are potent inhibitors, even at nanomolar concentrations, of both cytosolic and mitochondrial thioredoxin reductases, probably acting at the level of the selenol moiety (8, 57, 58, 135, 136, 162). The interaction of gold complexes with thioredoxin reductase and the corresponding mitochondrial alterations were recently reviewed (8). The inhibition of mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase, by altering the balance between formation and removal of hydrogen peroxide in favor of the first, results in a large increase in hydrogen peroxide inside the mitochondrion. This redox shift causes an increased permeability of the mitochondrial membrane, resulting from the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (8, 136, 137) (Fig. 4). As cancer cells are considered resistant to permeability transition that leads to cell apoptosis, the induction of this process is considered a therapeutic objective against cancer (79). Furthermore, hydrogen peroxide, released outside the mitochondrion, can activate the various signaling pathways and particularly the MAP kinase pathways (115, 139), further stimulating apoptosis. Gold complexes are shown to induce apoptosis in cancer cells (23, 29, 101, 115, 125, 139) and, in some cases, they are able to overcome the drug-induced drug resistance (92, 101). However, gold complexes are generally nonselective as they show comparable cytotoxicity toward both cancer cells and normal cells. Interestingly, some new gold(I) derivatives show a noticeable specificity, as they are able to induce apoptosis in cancer but not in normal cells (125). The ability to stimulate mitochondrial ROS production by gold ions is shared by several other metal ions or complexes (79).

FIG. 4.

Mitochondrial alterations due to thioredoxin reductase inhibition. In mitochondria, the inhibition of thioredoxin reductase alters the thioredoxin redox balance in favor of the oxidized form [Trx(SS)]. Oxidized thioredoxin acts by increasing the permeability properties of the mitochondrial membranes causing the release of proapoptotic factors.

Conclusions

A general agreement exists on the concept that ROS are not solely by-products of oxidative metabolism but, perhaps more important, are critical elements modulating cell-signaling events. In addition to a large body of experimental evidence, this view is also supported by the recognized presence of NADPH oxidases in nonphagocytic cells and by the notion that a free radical such as nitric oxide plays a critical role, acting as a second messenger.

Hydrogen peroxide, now recognized as a signaling molecule, is able to interact with thiols, although at different rates according to the type of thiol and the microenvironmental conditions present at the active site of several enzymes. In particular, peroxidases of the peroxiredoxin and GPx families are able to form sulfenic or selenenic acid groups at a very high rate. Cell thiols react faster than the other amino acids with oxidants and hence are good candidates to act as ROS sensors. Furthermore, some oxidation products of thiols can be readily reduced by the various cellular reducing systems. The most relevant reversible oxidation products of protein thiols are disulfides (including mixed disulfides with glutathione), sulfenic and sulfinic acids, and thiolsulfinates. Overall, the thiol redox state reflects the oxidant conditions of the cell. It is regulated by thioredoxin and glutathione systems that are in close redox communication with hydrogen peroxide through peroxiredoxins and glutathione peroxidases, respectively. In particular, the redox state of thioredoxin links the extent of cell oxidation to a specific physiologic response that differs from one cell compartment to another. For instance, the redox state of thioredoxin influences the membrane-permeability conditions in mitochondria, controls the MAP kinases signaling pathway in the cytosol, and regulates the binding of several transcription factors to DNA in the nucleus. Formation of hydrogen peroxide, according to its intensity and duration, can give completely different signals going from cell proliferation to apoptosis. Induction of the last condition can be relevant for anticancer therapy.

The study of the events linking thiol chemistry to redox signaling is a research area of large interest and great expansion. Several unresolved issues still await clarification. In particular, the chemical nature of the oxidants involved (in addition to hydrogen peroxide), the magnitude and location of their production, the type and extent of oxidation of the sensor thiols, the regeneration of the native form from their oxidation products, and so on, are important.

The full elucidation of the pathways linking redox alterations to cellular changes might provide insight into a large number of pathophysiologic conditions from degenerative diseases to cancer. In addition, the obtained information will allow the identification of redox targets to address specifically designed drugs.

Abbreviations

AP-1, activator protein-1; ASK1, apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; Grx, glutaredoxin; GST, glutathione transferase; HIF-1α, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α; Keap1, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein-1; MAP kinase, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MSR, methionine sulfoxide reductase; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; Nrf2, nuclear erythroid-related factor 2; PKA, protein kinase A; PKC, protein kinase C; Prx, peroxiredoxin; PTP, protein tyrosine phosphatase; Ref-1, redox factor-1; RNR, ribonucleotide reductase; RNS, reactive nitrogen species; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; Trx, thioredoxin; TrxR, thioredoxin reductase.

SOURCE:

Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008 Sep; 10(9): 1549–1564.

Alberto Bindoli,1 Jon M. Fukuto,2 and Henry Jay Forman3 1Institute of Neurosciences (CNR) c/o Department of Biological Chemistry, University of Padova (Italy). 2Department of Pharmacology, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California. 3School of Natural Sciences, University of California Merced, Merced, California.

Thiol Chemistry in Peroxidase Catalysis and Redox Signaling https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2693905/

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)