应激性高血糖 Stress Hyperglycemia

Critical Care. 2013; 17(2): 305.

Stress hyperglycemia: an essential survival response!

Paul E Marik corresponding author1 and Rinaldo Bellomo2

1Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA, USA

2Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Research Centre, Melbourne, Australia

Abstract

Stress hyperglycemia is common in critically ill patients and appears to be a marker of disease severity. Furthermore, both the admission as well as the mean glucose level during the hospital stay is strongly associated with patient outcomes.Clinicians, researchers and policy makers have assumed this association to be causal with the widespread adoption of protocols and programs for tight in-hospital glycemic control. However, a critical appraisal of the literature has demonstrated that attempts at tight glycemic control in both ICU and non-ICU patients do not improve health care outcomes.

We suggest that hyperglycemia and insulin resistance in the setting of acute illness is an evolutionarily preserved adaptive responsive that increases the host's chances of survival. Furthermore, attempts to interfere with this exceedingly complex multi-system adaptive response may be harmful. This paper reviews the pathophysiology of stress hyperglycemia and insulin resistance and the protective role of stress hyperglycemia during acute illness.

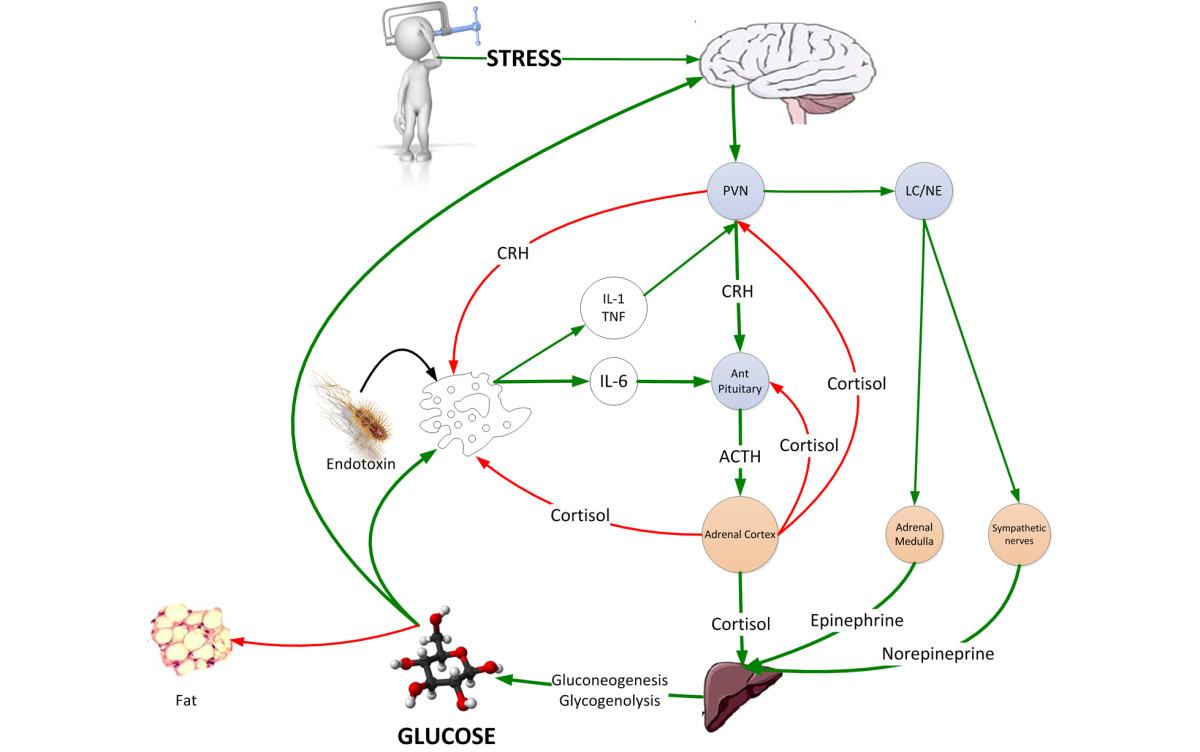

Figure 1

The neuroendocrine response to stress is characterized by gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis resulting in stress hyperglycemia providing the immune system and brain with a ready source of fuel. ACTH, adrenocorticotrophic hormone; CRH, corticotrophin releasing hormone; LC/NE, locus ceruleus norepinephrine system; PVN, paraventricular nucleus.

In 1878, Claude Bernard described hyperglycemia during hemorrhagic shock [1]; and it is now well known that acute illness or injury may result in hyperglycemia, insulin resistance and glucose intolerance, collectively termed stress hyperglycemia. Numerous studies in both ICU and hospitalized non-ICU patients have demonstrated a strong association between stress hyperglycemia and poor clinical outcomes, including mortality, morbidity, length of stay, infections and overall complications [2-5]. This association is well documented for both the admission as well as the mean glucose level during the hospital stay. Based on these data clinicians, researchers and policy makers have assumed this association to be causal with the widespread adoption of protocols and programs for tight or intensive in-hospital glycemic control. However, a critical appraisal of the data has consistently demonstrated that attempts at intensive glycemic control in both ICU and non-ICU patients do not improve health care outcomes [6-8]. Indeed, NICE-SUGAR, a large randomized, multi-center trial performed in 6,104 ICU patients, demonstrated that intensive glucose control (81 to 108 mg/dl) increased mortality when compared to conventional glucose control [9]. Although NICE-SUGAR targeted a blood glucose between 144 and 180 mg/dL, there is no evidence that targeting an even more tolerant level between 180 and 220 mg/dL would not, in fact, have been better (or worse). This information suggests that the degree of hyperglycemia is related to the severity of the disease and is an important prognostic marker. This is, however, not a cause and effect relationship. Indeed, Green and colleagues [10] demonstrated that hyperglycemia was not predictive of mortality in non-diabetic adults with sepsis after correcting for blood lactate levels, another marker of physiological stress. Tiruvoipati and colleagues [11] demonstrated that those patients with septic shock who had stress hyperglycemia had a significantly lower mortality than those with normal blood glucose levels. We suggest that hyperglycemia in the setting of acute illness is an evolutionarily preserved adaptive response that increases the host's chances of survival. Furthermore, iatrogenic attempts to interfere with this exceedingly complex multi-system adaptive response may be harmful. Only patients with severe hyperglycemia (blood glucose >220 mg/dl) may benefit from moderate glycemic control measures; however, this postulate is untested.

Acute illness, the stress response and stress hyperglycemia

The stress response is mediated largely by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathoadrenal system. In general, there is a graded response to the degree of stress. Cortisol and catecholamine levels correlate with the type of surgery, the severity of injury, the Glasgow Coma Scale and the APACHE score [12]. Adrenal cortisol output increases up to ten-fold with severe stress (approximately 300 mg hydrocortisone per day) [12]. In patients with shock, plasma concentrations of epinephrine increase 50-fold and norepinephrine levels increase 10-fold [13]. The adrenal medulla is the major source of these released catecholamines [13]. Adrenalectomy eliminates the epinephrine response and blunts the norepinephrine response to hemorrhagic shock [13]. The increased release of stress hormones results in multiple effects (metabolic, cardiovascular and immune) aimed at restoring homeostasis during stress. The HPA axis, sympathoadrenal system and proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-6) act collectively and synergistically to induce stress hyperglycemia.

The neuroendocrine response to stress is characterized by excessive gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis and insulin resistance (Figure (Figure1)1) [5]. Stress hyperglycemia, however, appears to be caused predominantly by increased hepatic output of glucose rather than impaired tissue glucose extraction. The metabolic effects of cortisol include an increase in blood glucose concentration through the activation of key enzymes involved in hepatic gluconeogenesis and inhibition of glucose uptake in peripheral tissues such as the skeletal muscles [5]. Both epinephrine and norepinephrine stimulate hepatic gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis; norepinephrine has the added effect of increasing the supply of glycerol to the liver via lipolysis. Inflammatory mediators, specifically the cytokines TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, and C-reactive protein, also induce peripheral insulin resistance (Figure (Figure2)2) [5]. In addition, the altered release of adipokines (increased zinc-alpha2 glycoprotein and decreased adiponectin) from adipose tissue during acute illness is thought to play a key role in the development of insulin resistance [14]. The degree of activation of the stress response and the severity of hyperglycemia are related to the intensity of the stressor and the species involved. Hart and colleagues [15] demonstrated that hemorrhage, hypoxia and sepsis were amongst those stressors that resulted in the highest epinephrine and norepinephrine levels. In reviewing the literature, we have demonstrated large interspecies differences in the degree of activation of the HPA axis with stress, with humans having the greatest increase in serum cortisol level (Figure (Figure3)3) [16].

Figure 2

Postulated interaction between the insulin signaling pathway and activation of the pro-inflammatory cascade in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance in sepsis. GLUT, glucose transporter; IκB, inhibitor κB; IKK, inhibitor κB kinase; IRS-1, insulin receptor substrate-1; LBP, lipopolysaccharide binding protein; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B; NO, nitric oxide; TLR4, Toll-like receptor-4.

Figure 3

Variability of the basal and stress cortisol level amongst various animal species[16]. Dom. cat, domestic cat; R monkey, rhesus.

Mild to moderate stress hyperglycemia is protective during stress and critical illness

Stress hyperglycemia and insulin resistance are evolutionarily preserved responses that allow the host to survive during periods of severe stress [17]. Insects, worms and all verterbrates, including fish, develop stress hyperglycemia when exposed to stress [17,18]. In animal models of hemorrhagic shock the administration of a hypertonic glucose solution increased cardiac output, blood pressure and improved survival [19]. In these experiments, similar osmolar doses of saline or mannitol, with greater accompanying fluid volumes, failed to produce the sustained blood pressure changes or to improve the survival.

Glucose is largely utilized by tissues that are non-insulin dependent, and these include the central and peripheral nervous system, bone marrow, white and red blood cells and the reticuloendothelial system [20]. It has been estimated that, at rest, non-insulin mediated glucose uptake accounts for 75 to 85% of the total rate of whole glucose disposal. Glucose is the primary source of metabolic energy for the brain. Cellular glucose uptake is mediated by plasma membrane glucose transporters (GLUTs), which facilitate the movement of glucose down a concentration gradient across the non-polar lipid cell membrane [20]. These transporters are members of a family of structurally related facilitative glucose transporters that have distinct but overlapping tissue distribution. Although 14 GLUT isoforms have been identified in the human genome, glucose uptake per se is facilitated by GLUT-1, GLUT-3 and GLUT-4 in various tissues. Insulin increases GLUT-4-mediated glucose transport by increasing translocation of GLUT-4 from intracellular stores to the cell membrane [20]. Thermal injury and sepsis have been demonstrated to increase expression of GLUT-1 mRNA and protein levels in the brain and macrophages [21,22]. Concomitantly, stress and the inflammatory response result in decreased translocation of GLUT-4 to the cell membrane. It is likely that proinflammatory mediators, particularly TNF-α and IL-1, are responsible for the reciprocal effects on the surface expression of these glucose transporters (Figure (Figure2)2) [5]. Elevated TNF-α directly interferes with insulin signal transduction through the phosphorylation of various molecules along the insulin-signaling pathway. During infection, the upregulation of GLUT-1 and downregulation of GLUT-4 may play a role in redistributing glucose away from peripheral tissues towards immune cells and the nervous system.

For glucose to reach a cell with reduced blood flow (ischemia, sepsis), it must diffuse down a concentration gradient from the bloodstream, across the interstitial space and into the cell. Glucose movement is dependent entirely on this concentration gradient, and for adequate delivery to occur across an increased distance, the concentration at the origin (blood) must be greater. Stress hyperglycemia results in a new glucose balance, allowing a higher blood 'glucose diffusion gradient' that maximizes cellular glucose uptake in the face of maldistributed microvascular flow [23]. These data suggest that moderate hyperglycemia (blood glucose of 140 to 220 mg/dL) maximizes cellular glucose uptake while avoiding hyperosmolarity. Furthermore, acute hyperglycemia may protect against cell death following ischemia by promoting anti-apoptotic pathways and favoring angiogenesis. In a murine myocardial infarction model, Malfitano and colleagues [24] demonstrated that hyperglycemia increased cell survival factors (hypoxia inducible factor-1α, vascular endothelial growth factor), decreased apoptosis, reduced infarct size and improved systolic function. In this study, hyperglycemia resulted in increased capillary density and a reduction in fibrosis. In vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that cardiomyocytes exposed to an insulin-free medium supplemented with high glucose concentrations are resistant to pathological insults such as ischemia, hypoxia and calcium overload [25].

Macrophages play a central role in the host response to injury, infection and sepsis. Macrophage activities include antigen presentation, chemotaxis, phagocytosis, bactericidal activity, cytokine secretion and wound repair. Glucose is the primary metabolic substrate for the macrophage and efficient glucose influx is essential for optimal macrophage function. Macrophages and neutrophils require NADPH for the formation of the reactive oxygen species, nitric oxide and superoxide as well as many biosynthetic pathways. Metabolism of glucose via the pentose pathway provides the metabolic intermediates required for the generation of NADPH. Following thermal injures, trauma and sepsis, non-insulin mediated glucose uptake is increased. The majority of the increased glucose uptake occurs in macrophage rich tissues [26,27]. These data suggest that the increased energy requirements of activated macrophages and neutrophils during infection and tissue injury are regulated by enhanced cellular glucose uptake related to the increased glucose diffusion gradient and increased expression of glucose transporters. In addition, these mechanisms ensure adequate glucose uptake by neuronal tissue in the face of decreased microvascular flow. Iatrogenic normalization of blood glucose may therefore impair immune and cerebral function at a time of crises. Indeed, two independent groups of investigators using microdialysis and brain pyruvate/lactate ratios demonstrated that attempts at blood glucose normalization in critically ill patients with brain injury were associated with a greater risk of critical reductions in brain glucose levels and brain energy crisis [28,29]. Similarly, Duning and colleagues [30] demonstrated that hypoglycemia worsened critical illness-induced neurocognitive dysfunction. Multiple studies have demonstrated that even moderate hypoglycemia is harmful and increases the mortality of critically ill patients [31,32]. In summary, these data suggest that stress hyperglycemia provides a source of fuel for the immune system and brain at a time of stress and that attempts to interfere with this evolutionarily conserved adaptive response is likely to be harmful.

The deleterious effects of chronic hyperglycemia and the benefit of acute hyperglycemia: balancing the good with the bad

Chronic hyperglycemia in patients with diabetes is associated with a myriad of harmful complications. The adverse outcomes associated with chronic hyperglycemia are attributed to the pro-inflammatory, pro-thrombotic and pro-oxidant effects observed with increased glucose levels. Brownlee [33] has suggested a unifying mechanism to explain the pathobiology of the long-term complications of diabetes - the overproduction of superoxide by the mitochondrial electron chain. The duration and degree of hyperglycemia appears to be critical in determining whether hyperglycemia is protective or harmful. This contention is supported by a number of experimental models. Acute hyperglycemia limits myocardial injury following hypoxia [34]; however, chronic treatment of cardiomyocytes with a high glucose content medium increased the rate of cell death [35]. This issue was specifically addressed by Xu and colleagues [36], who measured infarct size following a left coronary arteryischemia/reperfusion injury following short- (4 weeks) and long-term (20 weeks) hyperglycemia. In this study, the number of dead myocytes decreased with short-term hyperglycemia while the number of dead myocytes increased markedly in the 20 week hyperglycemia group compared with the time-matched control group. Furthermore, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK 1/2), which plays an important role in cell proliferation and protein synthesis, increased with short-term hyperglycemia but was reduced with long-term hyperglycemia. In a similar study, Ma and colleagues [25] demonstrated that 2 weeks of streptozotocin-induced diabetes reduced pro-apoptotic signals and myocardial infarct size compared with normoglycemic controls or rats that had been diabetic for 6 weeks. In this study, phosphorylation of AKT, a prosurvival signal, was significantly increased after 2 weeks of diabetes. However, after 6 weeks of diabetes, lipid peroxidation was increased and levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and plasma nitric oxide were reduced compared with controls or rats diabetic for 2 weeks. These studies differ from those of Van den Berghe and colleagues [37,38], who in experimental models have demonstrated that acute hyperglycemia induces mitochondrial and organ dysfunction. However, it must be recognized that similar to their 'landmark' study in critically ill patients [39], these animals received parenteral nutrition. Parenteral nutrition results in cellular glucose overload and is an independent predictor of increased morbidity and mortality [40-42].

These data suggest that acute hyperglycemia may be protective and may result in greater plasticity and cellular resistance to ischemic and hypoxic insults. It is possible, although not proven, that severe stress hyperglycemia (blood glucose >220 mg/dL) may be harmful. Due to its effects on serum osmolarity, severe stress hyperglycemia may result in fluid shifts. In addition, severe hyperglycemia exceeds the renal threshold, resulting in an osmotic diuresis and volume depletion. It is, however, unclear at what threshold stress hyperglycemia may become disadvantageous. It is likely that severe stress hyperglycemia may occur more frequently in patients with underlying impaired glucose tolerance [43].

The Leuven trial and glycemic control in the ICU

In 2001, Van den Berghe and coworkers [39] published the 'Leuven Intensive Insulin Therapy Trial' in which they demonstrated that tight glycemic control (targeting a blood glucose of 70 to 110 mg/dL) using intensive insulin therapy improved the outcome of critically ill surgical patients. The results of this single-center, investigator-initiated and unblinded study have yet to be reproduced. This study has a number of serious limitations with concern regarding the biological plausibility of the findings [8,44]. Following the above study, tight glycemic control became rapidly adopted as the standard of care in ICUs throughout the world. Tight glycemic control then spread outside the ICU to the step-down unit, regular floor and even operating room. Without any credible evidence that intensive glycemic control improves the outcome of hospitalized patients, this has become a world-wide preoccupation and 'compliance' with glycemic control is used as a marker of the quality of care provided. Indeed, as recently as 2012, the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline on the management of hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients stated that 'observational and randomized controlled studies indicate that improvement in glycemic control results in lower rates of hospital complications' and they provide strong recommendations for glycemic control [45]. The 2012 Clinical Practice Guidelines published by the American College of Critical Care Medicine suggest that 'a blood glucose > 150 mg/dl should trigger interventions to maintain blood glucose below that level and absolutely < 180 mg/dl' [46]. We believe the evidence demonstrates that these assertions and recommendations are without a scientific basis and may be potentially detrimental to patients.

Conclusion

Although an association between the degree of hyperglycemia and poor clinical outcomes exist in the hospitalized patient, there are few data demonstrating causation. Randomized, controlled studies do not support intensive insulin therapy. Furthermore, improving care through the acute treatment of mild or moderate hyperglycemia in the acutely ill hospitalized patient lacks biologic plausibility. We advocate more studies comparing standard care (glycemic target between 145 and 180 mg/dL) as delivered in the NICE-SUGAR trial with a more tolerant management of stress hyperglycemia (target between 180 and 220 mg/dL).

Abbreviations

GLUT: glucose transporter; HPA: hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal; IL: interleukin; TNF: tumor necrosis factor.Stress hyperglycemia: an essential survival response!

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3672537/

Increased blood glucose in patients with sepsis

Infection/sepsis Glucose

Summarized from Tiruvoipati R, Chiezey B, Lewis D et al. Stress hyperglycemia may not be harmful in critically ill patients with sepsis.J Critical Care 2012; 27:153-158

Frequent blood glucose measurement is one element of the routine intensive monitoring that all critically ill patients receive following admission to intensive care units. Transient increase in blood glucose concentration (hyperglycemia) is very common in this patient group. The significance of this so called stress hyperglycemia remains unclear.

Some studies have demonstrated that normalisation of blood glucose with insulin therapy reduces mortality among the critically ill, implying that stress hyperglycemia is a harmful state that warrants treatment. Other studies suggest stress hyperglycemia is harmless, or even perhaps a beneficial compensatory response to critical illness.

It seems increasingly likely that the significance depends not only on the severity of the hyperglycemia but also on the nature of the critical illness, and studies in this area are now focusing on specific patient groups within the community of the critically ill. A recently published retrospective study sought to determine the significance of stress hyperglycemia among patients admitted to intensive care with sepsis.

The study population comprised 297 septic patients admitted to the intensive care unit of an Australian teaching hospital over a five year period. All patients had blood glucose concentration estimated at least once every six hours for the duration of their stay in intensive care. A blood gas analyzer sited in the unit was used for these measurements.

Stress hyperglycemia was diagnosed if the mean of these blood glucose estimations exceeded 6.9 mmol/L. By this criterion 204 of the 297 (68.7 %) patients had stress hyperglycaemia and 93 (31.3 %) did not. The mean blood glucose of all patients with stress hyperglycemia was 8.7 mmol/L and the mean blood glucose of all those without stress hyperglycemia was 5.9 mmol/L.

Retrieval and analysis of patient records revealed that there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of age, gender, severity of sepsis, and a range of clinical and laboratory measurements.

The two groups had equal proportion of patients requiring mechanical ventilation and were not significantly different in terms of co-morbidity (with the sole exception of diabetes which was significantly more frequent in the stress hyperglycaemia group than among those without stress hyperglycaemia).

ICU mortality rates were however significantly different; 26.9 % of those without stress hyperglycemia died before discharge from ICU, this compared with just 14.8 % of those with stress hyperglycemia. This allowed the authors to conclude that stress hyperglycemia may not be harmful in critically ill patients with sepsis, and as long as the hyperglycemia is mild (<10.0 mmol/L) it should not be treated.Increased blood glucose in patients with sepsis

https://acutecaretesting.org/en/journal-scans/increased-blood-glucose-in-patients-with-sepsis

World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Sep 7; 15(33): 4132–4136.

Blood glucose control in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock

Hiroyuki Hirasawa, Shigeto Oda, and Masataka Nakamura

Hiroyuki Hirasawa, Shigeto Oda, Masataka Nakamura, Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Chiba University Graduate School of Medicine, 1-8-1 Inohana, Chuo, Chiba 260-8677, Japan

Abstract

The main pathophysiological feature of sepsis is the uncontrollable activation of both pro- and anti-inflammatory responses arising from the overwhelming production of mediators such as pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. Such an uncontrollable inflammatory response would cause many kinds of metabolic derangements. One such metabolic derangement is hyperglycemia. Accordingly, control of hyperglycemia in sepsis is considered to be a very effective therapeutic approach. However, despite the initial enthusiasm, recent studies reported that tight glycemic control with intensive insulin therapy failed to show a beneficial effect on mortality of patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. One of the main reasons for this disappointing result is the incidence of harmful hypoglycemia during intensive insulin therapy. Therefore, avoidance of hypoglycemia during intensive insulin therapy may be a key issue in effective tight glycemic control. It is generally accepted that glycemic control aimed at a blood glucose level of 80-100 mg/dL, as initially proposed by van den Berghe, seems to be too tight and that such a level of tight glycemic control puts septic patients at increased risk of hypoglycemia. Therefore, now many researchers suggest less strict glycemic control with a target blood glucose level of 140-180 mg/dL. Also specific targeting of glycemic control in diabetic patients should be considered. Since there is a significant correlation between success rate of glycemic control and the degree of hypercytokinemia in septic patients, some countermeasures to hypercytokinemia may be an important aspect of successful glycemic control. Thus, in future, use of an artificial pancreas to avoid hypoglycemia during insulin therapy, special consideration of septic diabetic patients, and control of hypercytokinemia should be considered for more effective glycemic control in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock.

Keywords: Blood glucose, Diabetes mellitus, Insulin, Hypercytokinemia, Inflammation mediators

INTRODUCTION

There are many pathophysiological changes during severe sepsis and septic shock, and one of the most striking is metabolic derangement. Among the metabolic changes, hyperglycemia is the most important[1,2]. Accordingly therapeutic approaches to hyperglycemia in the management of severe sepsis and septic shock have had much attention. Intensive insulin therapy became popular in the intensive care unit (ICU) after Van den Berghe’s research reporting its effectiveness on glycemic control[3,4]. However, a recent large-scale randomized trial indicated that such glycemic control is not effective in reducing ICU mortality and that glycemic control with intensive insulin therapy increases the risk of hypoglycemia, and complications arising from hypoglycemia[5]. Therefore, in this paper we will discuss the effectiveness of intensive insulin therapy in the ICU and the future perspectives on tight glycemic control from the viewpoint of the correlation between inflammatory hypercytokinemia and hyperglycemia.Blood glucose control in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2738808/