呼吸道上皮细胞和肺的抗感染研究

Respiratory epithelial cells orchestrate pulmonary innate immunity

REVELATION:

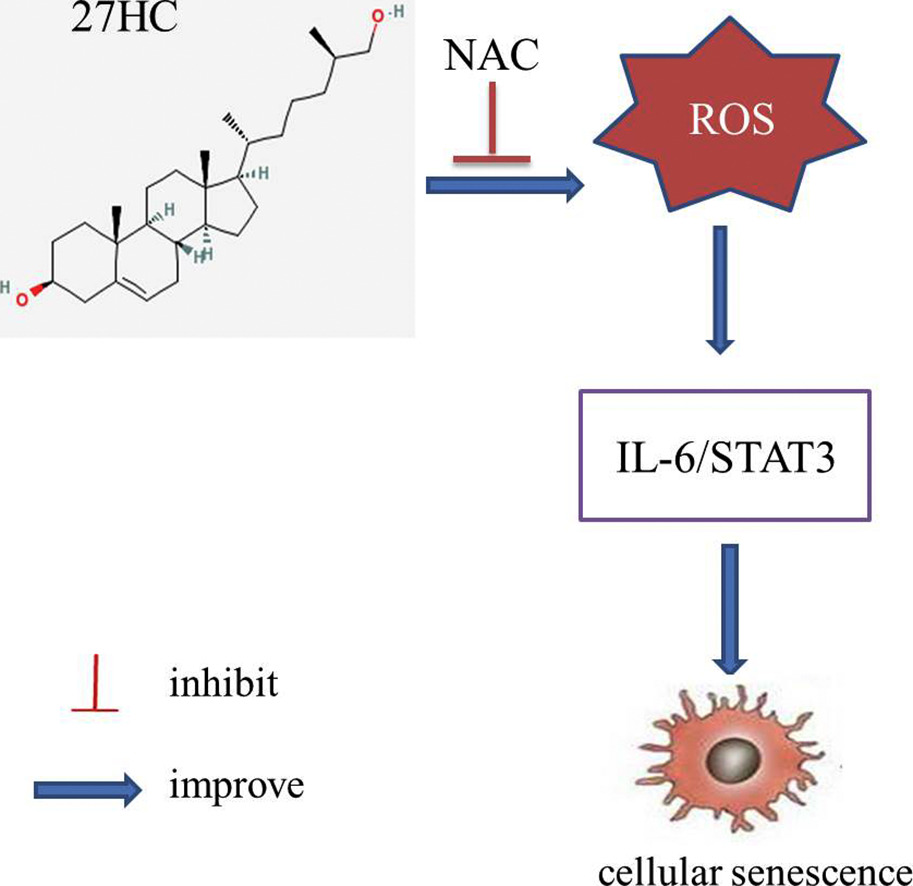

雾化疗法 (vitamin C,NAC, surfactant, negative ions...)

Expression of hydrolase in lung tissues

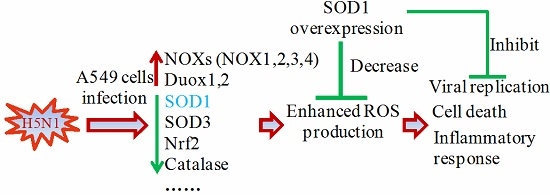

1. Influenza Virus H5N1 Infection Can Induce ROS Production for Viral Replication and Host Cell Death

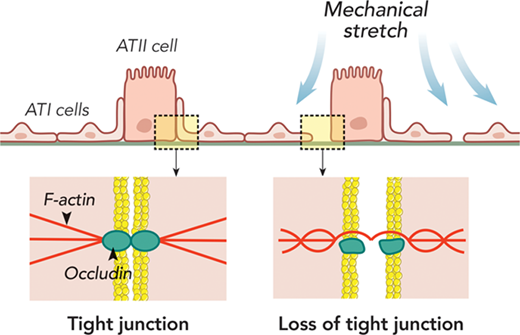

2. Influenza virus damages the alveolar barrier by disrupting epithelial cell tight junctions

3. Influenza-Induced Production of Interferon-Alpha is Defective in Geriatric Individuals, due to lower frequency of pDCs.

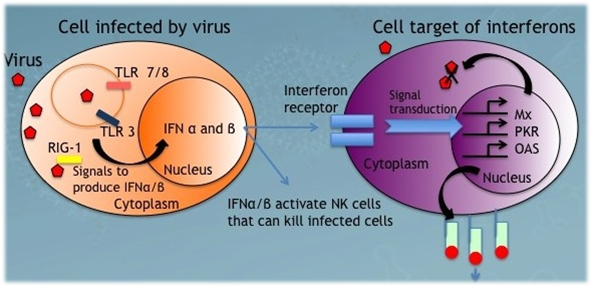

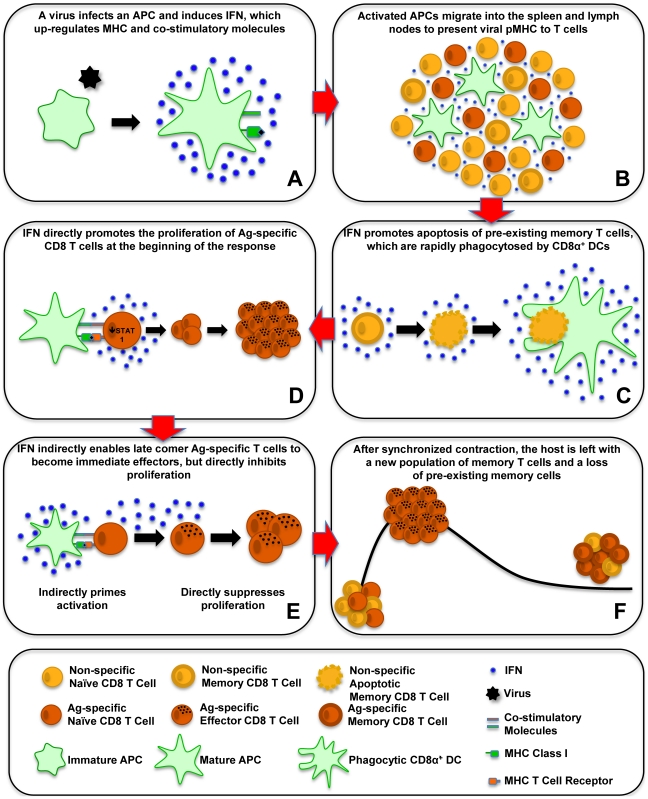

4. All interferons (alpha, beta and gamma) inhibit viral replication by interfering with the transcription of viral nucleic acid.

5,Omega 3 Fatty Acids May Reduce Bacterial Lung Infections Associated with COPD

6. High-dose vitamin C has therapeutic efficacy on acute pancreatitis. The potential mechanisms include promotion of anti-oxidizing ability of AP patients, blocking of lipid peroxidation in the plasma and improvement of cellular immune function.

7. Low density lipoprotein (LDL) inhibits endothelium-dependent relaxation. Vitamin C reduced the inhibitory effect of LDL.

8. mechanical ventilation, particularly where significant overstretch occurs, may drive the pathogenesis of fibrosis in patients with ARDS.

9.AMPK activator, metformin, restored their phagocytic capacity to uptake both apoptotic neutrophils and NETs.

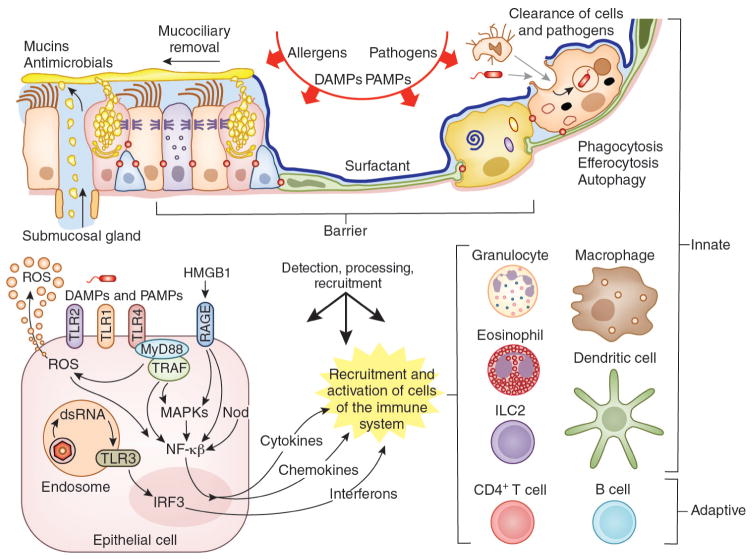

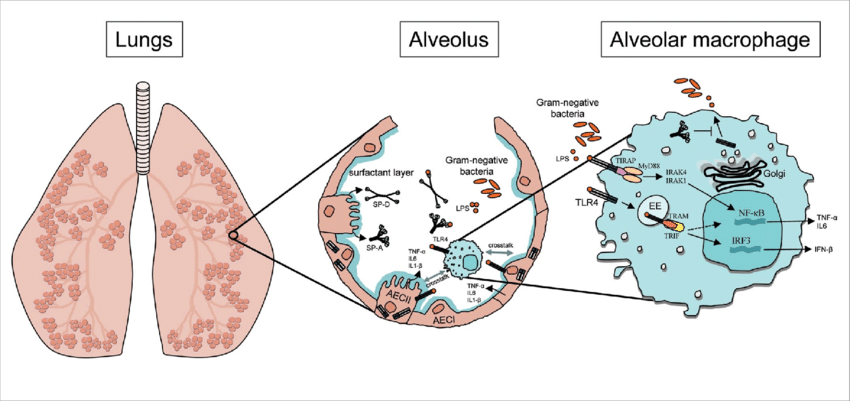

10. sentinel epithelial cells and innate immune cells might be essential components of pathogenesis,

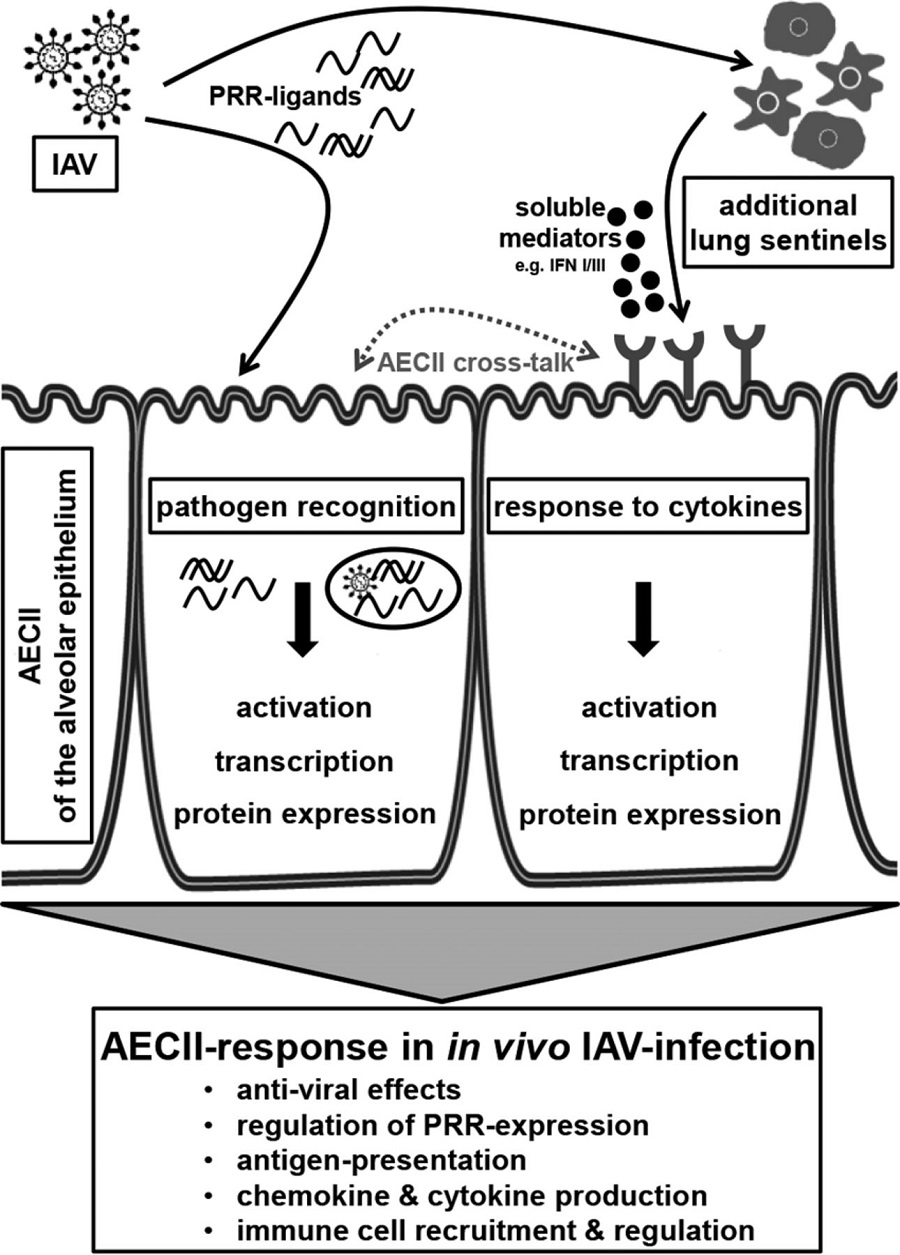

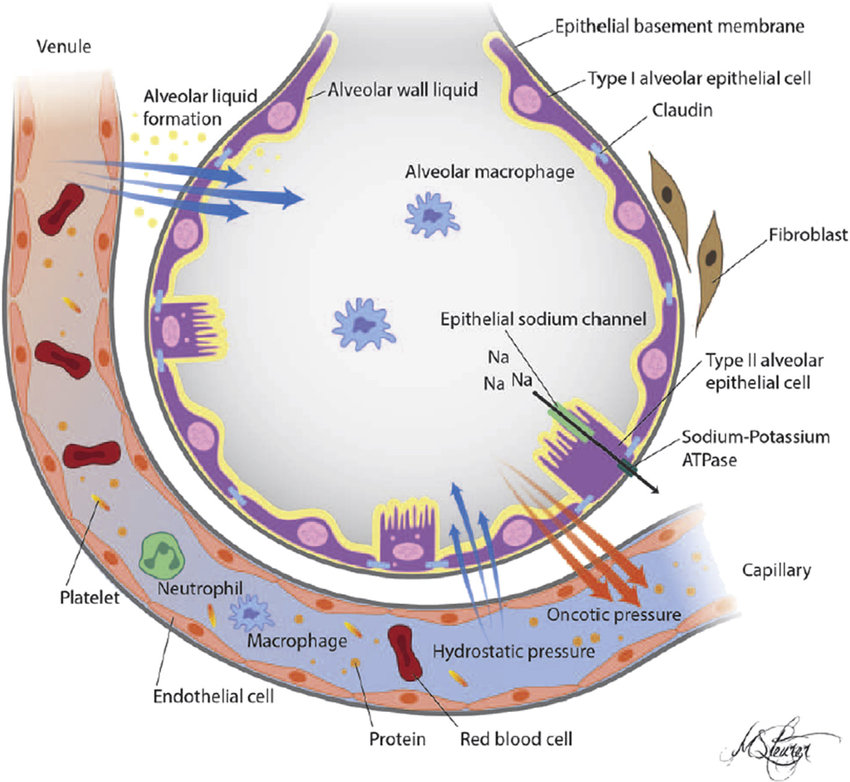

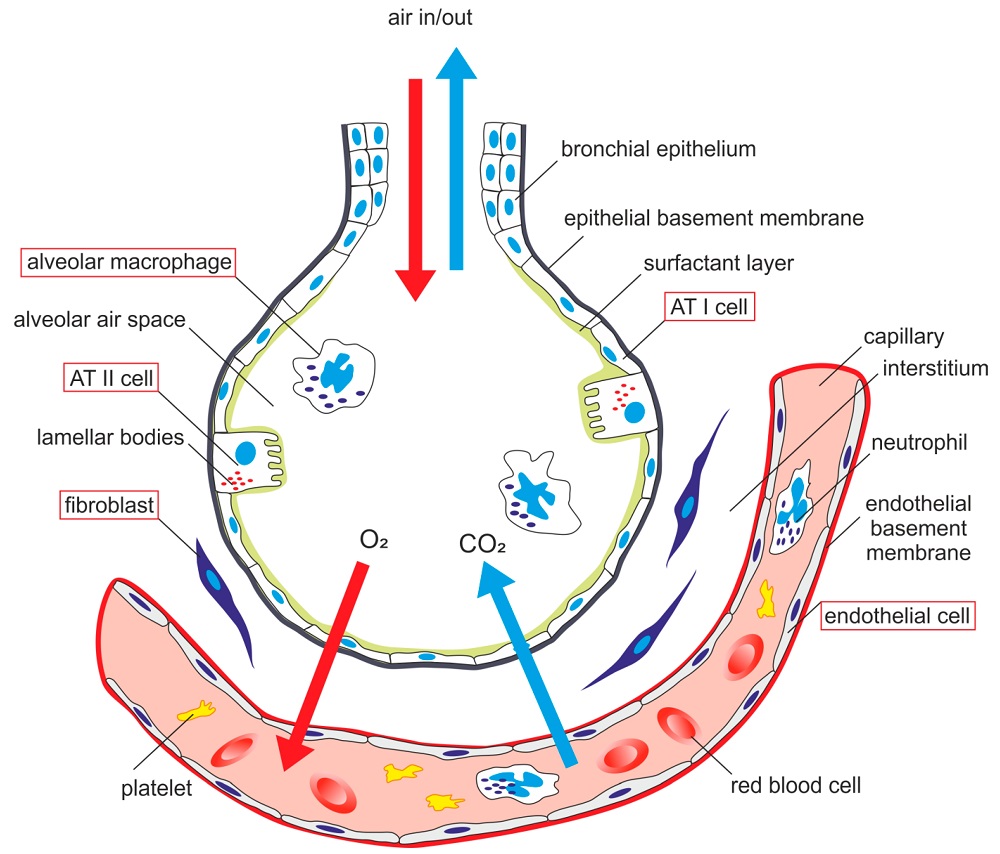

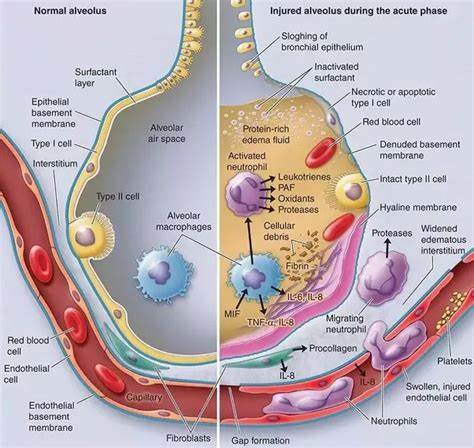

11.A major cause of respiratory failure during influenza A virus (IAV) infection is damage to

the epithelial–endothelial barrier of the pulmonary alveolus.12.AECs produces inflammatory cytokines,like interferons,defensins,and chemokines in reponse to viral infections

13. MSCs from bone marrow can transfer mitochondria to alveoli macrophage

14. Respiratory epithelial cells orchestrate pulmonary innate immunity

15. The AEC-induced migration of blood monocytes could be reduced by 30% to 90% by neutralizing MCP-1. AEC secrete high levels of MCP-1 and the murine IL-8 homologs KC and MIP-2 upon stimulation with LPS (20).

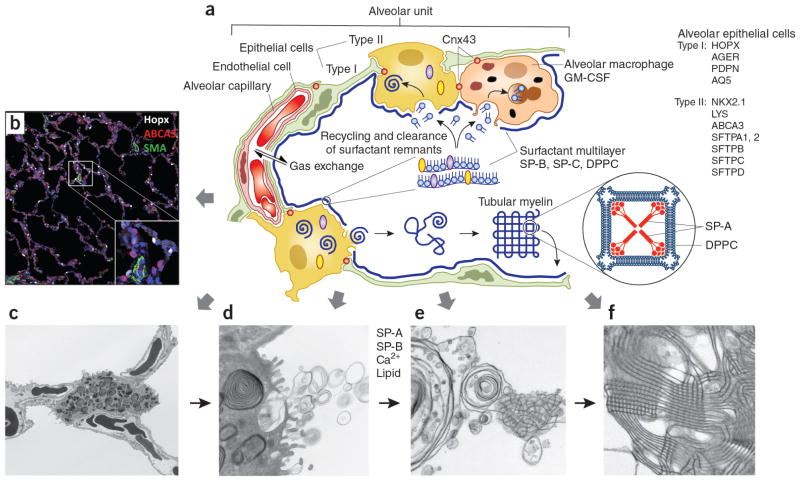

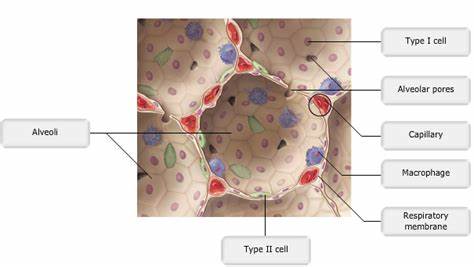

16. AEC II are cuboidal cells that constitute around 15% of total lung cells and cover about 7% of the total alveolar surface. AEC II are responsible for epithelium reparation upon injury and ion transport. AEC II contribute also to lung defense by secreting antimicrobial products such as complement, lysozyme, and surfactant proteins (SP). AEC II secrete a broad variety of factors, such as cytokines and chemokines, involved in activation and differentiation of immune cells and have been described to be able to present antigen to specific T cells (6–11).

17. activation of apoptosis and necroptosis pathways in monocytes differentially contributed to the immune response of monocytes upon H7N9 infection

18.IFNs-I were found to systemically activate natural killer (NK) cell activity and activity of other cells of the immune system, such as antigen-presenting dendritic cells (DC) and CD4 and CD8 T cells.

19.Respiratory Epithelial Cells as Master Communicators during Viral Infections

20.AT2 cells are the major cell type that produce GM-CSF during IAV infection and epithelial cell-produced GM-CSF contributes to disease attenuation and survival

21.IAV has also been shown to upregulate PD-L1 expression in human airway epithelial cultures. IAV-induced expression of PD-L1 is dependent on type I IFN signaling in mouse tracheal epithelial cultures and thus may represent a generalized response to viral infection [53••]. Similar to the studies with RSV, inhibition of PD-1 signaling during IAV infection enhances CD8+ T cell functions in a co-culture model and in the airways of infected mice [53••]. Thus, by increasing expression of PD-L1 by epithelial cells, viruses downregulate the effector functions of CD8+ T cells, thereby promoting viral replication.

22. GM-CSF is secreted by alveolar epithelial cells upon viral infection and also in response to TNF-α produced by stimulated alveolar macrophages [65••, 70]. GM-CSF promotes proliferation of AT2 cells, which leads to repair of damaged epithelium and restoration of its barrier functions [70].

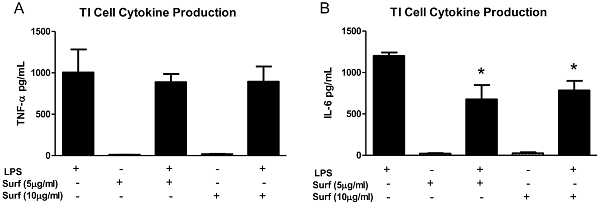

23. type 1 alveoli epithelial cells produce more IL-1, IL-6, TNFalpha than AT2 cells in response to LPS stimulation. Exogenous surfactant decreases LPS-stimulated TI cell cytokine production

One of the most striking findings in this study was the dramatic increase in TNF-α and IL-6 production in the co-cultures of TI cells and macrophages. Exposing cultured TI cells to conditioned media from LPS-treated macrophages suggested that while TI cells do respond to inflammatory mediators liberated by activated macrophages by increasing TNF-α secretion, cell-cell interaction between macrophages and TI cells is a much more potent factor in modulating TI cell cytokine release. Conditioned media from activated macrophages decreased the levels of TI cell IL-6 compared to LPS-stimulated TI cells alone, while LPS treatment of co-cultures of TI cells and macrophages significantly increased IL-6 production. The IL-6 conditioned media experiments reinforce the notion that cell-cell interaction between TI cells and macrophages is powerful, as co-culture of these cells overcomes the inhibition of IL-6 production in TI cells by inhibitory mediators released by activated macrophages. While the exact cell of origin of the IL-6 in this instance is unclear, these results not only make a strong case for TI cells as key participants in the immune response of the lung, but they also suggest that the interaction between macrophages and TI cells may be equally important.

Our data has shown that TI and TII cells not only respond differently to LPS stimulation, but there exists the possibility that the two alveolar cell types work in concert within their microenvironment to provide a balanced inflammatory response to infection. One could postulate that TI cells may serve to heighten the pro-inflammatory response with enhanced cytokine production, particularly in the presence of alveolar macrophages, while TII cells, through the production of surfactant and relatively modest cytokine expression, provide more of an anti-inflammatory response by trying to contain inflammation.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0055545

http://cleverwaysoflearning.tumblr.com/

http://www.bio.miami.edu/tom/courses/bil265/bil265goods/15_hormones2.html

HIihtlights

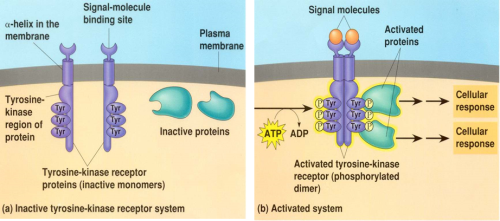

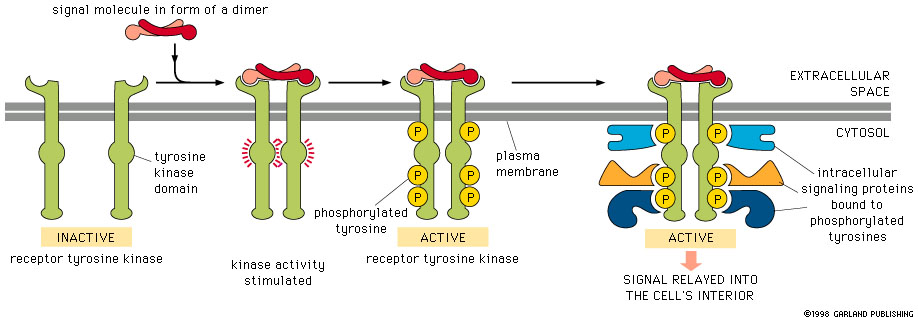

1. H2O2 up-regulates Fas expression through the activation of protein tyrosine kinase in ECs.

2, Various cells express Fas, whereas Fas-L is expressed predominantly in activated T cells.

3. Vitamin C is an inhibitor of protein tyrosine kinase

Receptor Tyrosine Kinases (RTKs) in the Akt Pathway

Receptor Tyrosine Kinases (RTKs) are widely expressed transmembrane proteins that act as receptors for growth factors, neurotrophic factors, and other extracellular signaling molecules. Upon ligand binding, they undergo tyrosine phosphorylation at specific residues in the cytoplasmic tail. This leads to the binding of protein substrates and/or the establishment of docking sites for adaptor proteins involved in RTK-mediated signal transduction. The RTKs listed below have been associated with activation of the Akt signaling pathway, which promotes cell growth, survival, and proliferation. Due to these downstream effects, unregulated activation of RTKs can lead to cancer. Highlighting the significant role RTKs can have in cancer, small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors are commonly used in cancer therapy.

Receptor Tyrosine Kinases (RTKs) in the Akt Pathway ...

http://www.cell.com/trends/pharmacological-sciences/fulltext/S0165-6147(11)00159-3

A tyrosine kinase is an enzyme that can transfer a phosphate group from ATP to a protein in a cell. It functions as an "on" or "off" switch in many cellular functions. Tyrosine kinases are a subclass of protein kinase. The phosphate group is attached to the amino acid tyrosine on the protein.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tyrosine_kinase

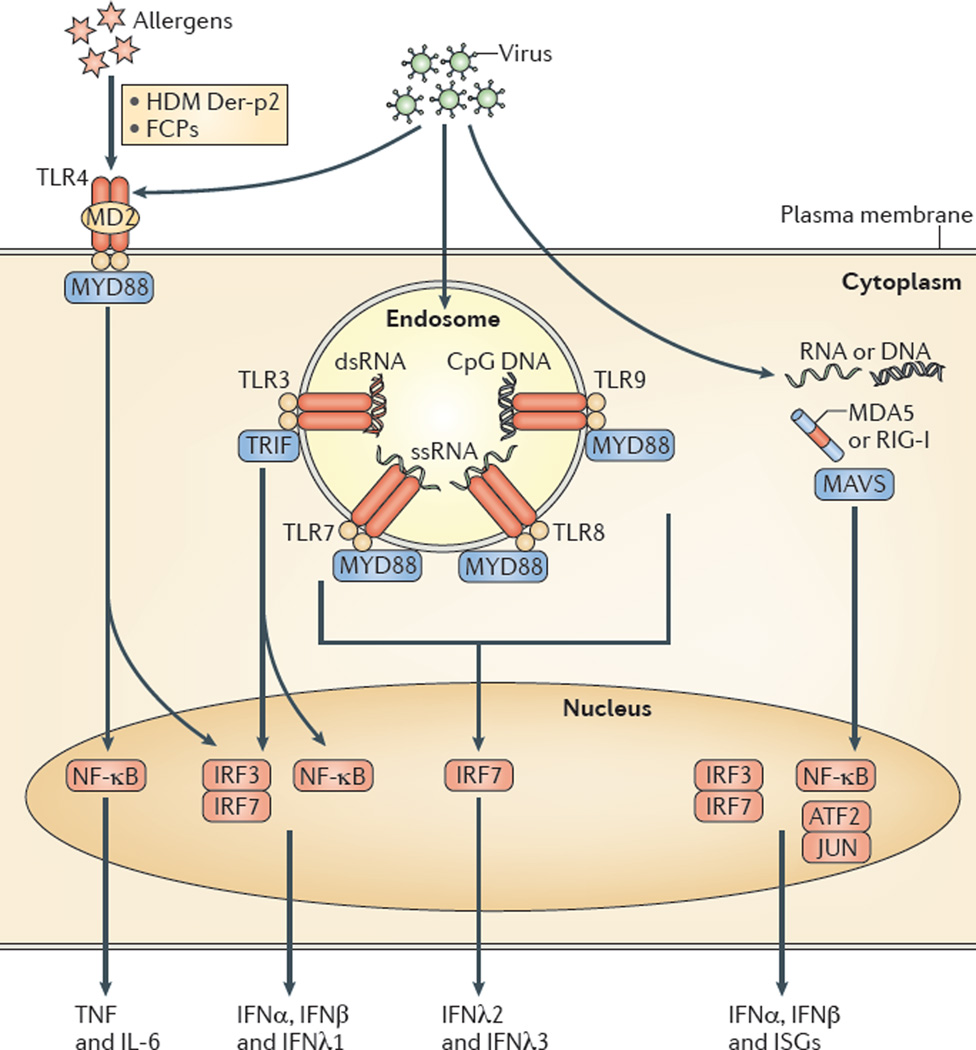

AECs mediate innate immunity

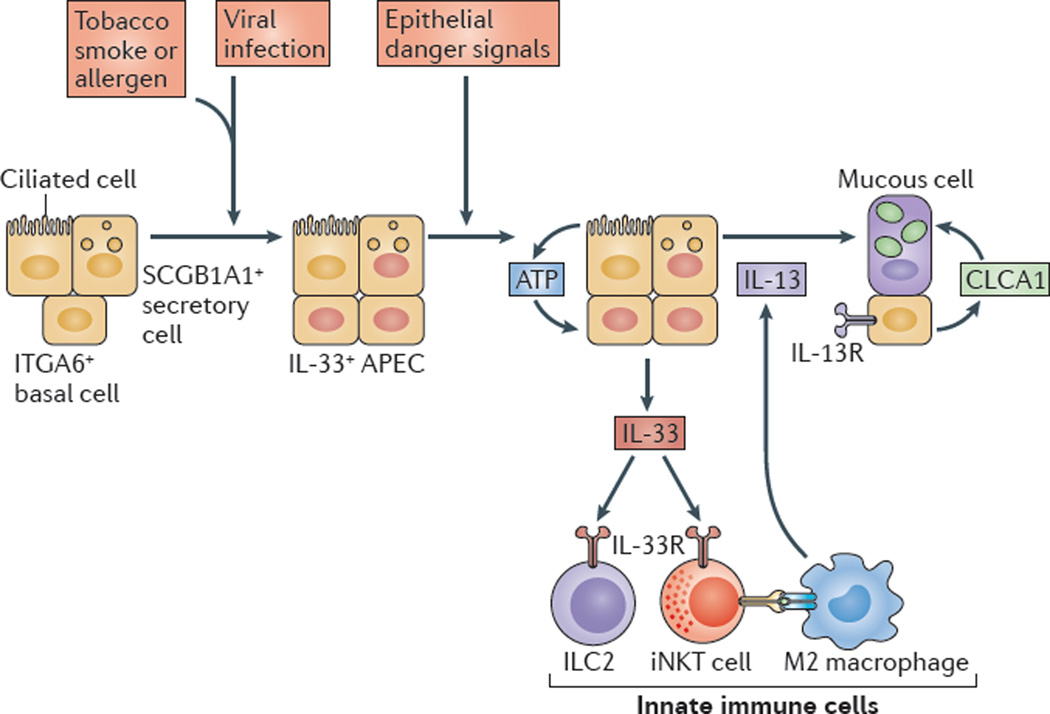

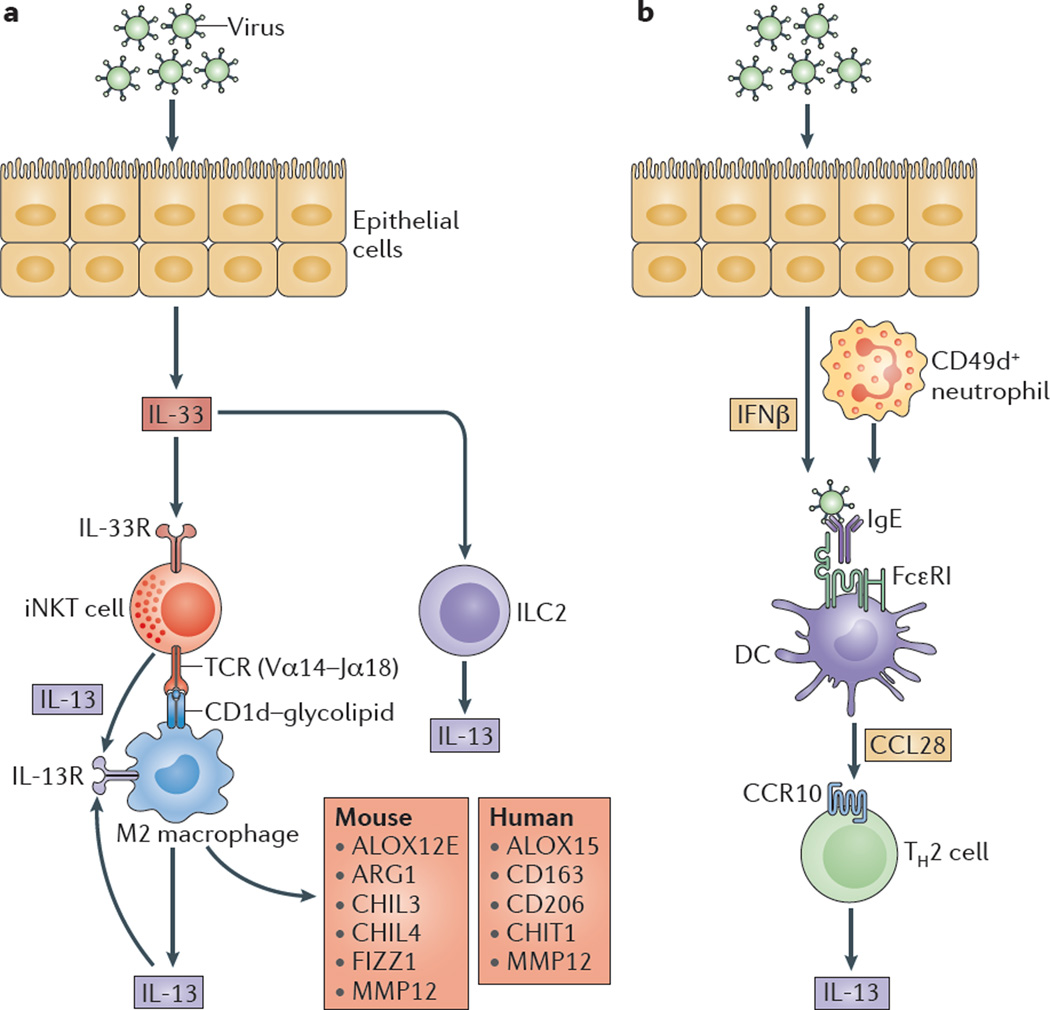

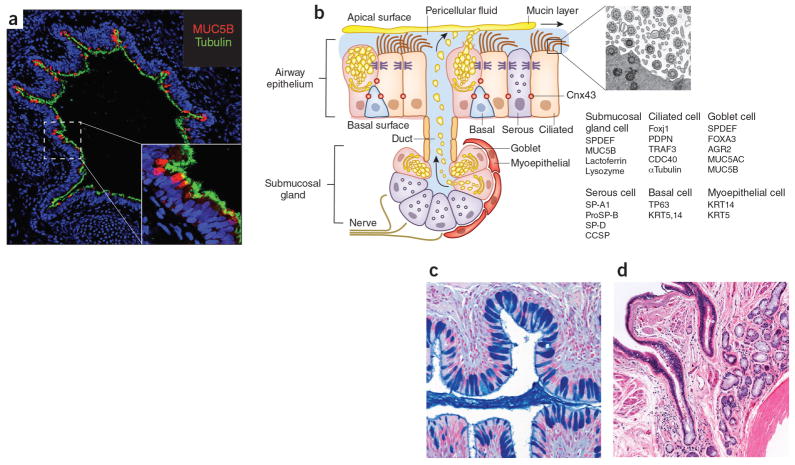

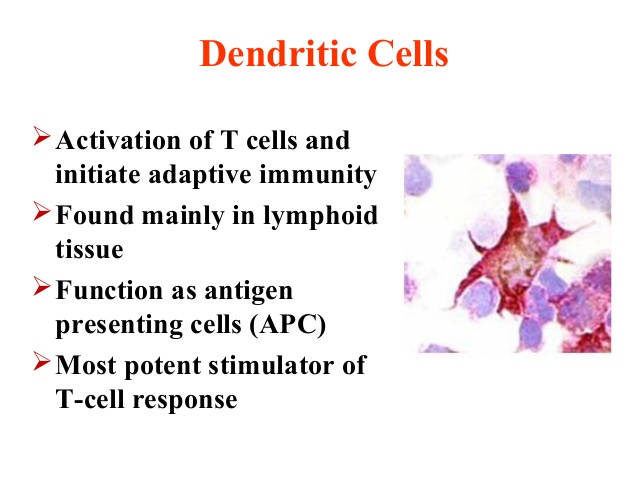

AECs act as a first line of defense against antigens that have escaped mucociliary clearance. Single cell‐RNA sequencing studies have shown that AECs can be subdivided into multiple subtypes 3, 5. The best characterized subtypes include squamous type I and cuboidal type II cells, which are responsible for gas exchange with the endothelium and production of pulmonary surfactant, respectively 11. Being endowed with an arsenal of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as Toll‐like receptors (TLRs), Nod‐like receptors and retinoic acid‐inducible gene (RIG)‐I‐like receptors, AECs promptly sense pathogen‐associated molecules and initiate NF‐κB‐dependent inflammatory cascades through the release of antimicrobial peptides, cytokines and chemokines 11. Of particular importance are microbial ssRNA‐ and CpGDNA‐sensing TLR‐3, TLR‐7, TLR‐9, RIG‐I and melanoma differentiation‐associated protein‐5, which have been implicated in the rapid release of interferon (IFN)‐β, granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (GM‐CSF), interleukin (IL)‐6 and IL‐8, a potent neutrophil‐recruiting chemokine 12. This robust cytokine response is critical to subsequently stimulate adaptive immunity, and neutralize the harmful effects of foreign pathogens.

However, owing to the hypersensitivity of AEC PRRs, these receptors can sometimes become diverted to mediate autoimmunity. For example, in mouse models of allergic asthma, activation of TLR‐4 by dust mites on AECs is associated with local production of IL‐25, IL‐33, GM‐CSF and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) 13. These cytokines work in concert to stimulate activation and pulmonary infiltration of dendritic cells (DCs), lymphocytes, neutrophils and eosinophils 13. In addition, studies of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis have shown that GM‐CSF is specifically necessary for lung homeostasis, such that GM‐CSF autoantibodies or genetic deletion causes abnormal lung development and surfactant accumulation, despite normal peripheral hematopoiesis 14-16. Together these studies highlight a unique ability of AECs to undergo ‘innate immune mimicry’, and orchestrate inflammation and autoimmunity. Therefore, the contribution of AECs in the pulmonary microenvironment is essential to understanding both normal and pathologic lung function.The innate immune architecture of lung tumors and its implication in disease progression - Milette - 2019 - The Journal of Pathology - Wiley Online Library

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/path.5241

ijms-20-00831-g001.png (3272×2795)

https://www.mdpi.com/ijms/ijms-20-00831/article_deploy/html/images/ijms-20-00831-g001.png

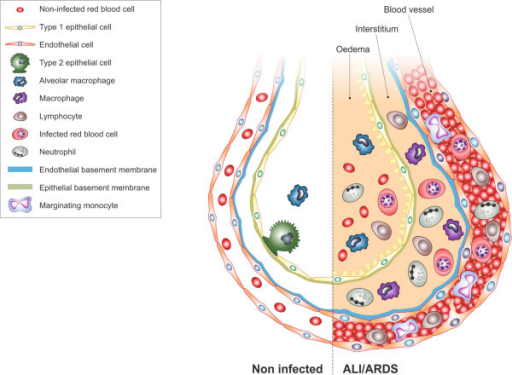

F10: Diagram showing main findings of the paper. Using scanning electron microscopy a number of differences are visible in ALI/ARDS mouse lungs when compared to lungs of non-infected mice. In summary the endothelium of the capillaries ALI/ARDS lungs are swollen with distended cytoplasmic extensions and thickened basement membranes. The capillaries themselves are completely congested with leukocytes, niRBC and iRBC, in some instances bridges between iRBC and endothelium surfaces are visible. The alveolar space contains oedema, inflammatory cells and projections from septum epithelium, the septum are thick and full of leukocytes. ALI/ARDS: acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. The layout of a single alveoli split to compare non-diseased and diseased lungs is based on a number of previous papers and books [25,16,27].

https://openi.nlm.nih.gov/detailedresult.php?img=PMC4062769_1475-2875-13-230-10&req=4

https://www.lhsc.on.ca/critical-care-trauma-centre/acute-respiratory-distress-syndrome-ards

J Virol. 2015 Apr;89(8):4655-67. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03095-14. Epub 2015 Feb 11.

A(H7N9) virus results in early induction of proinflammatory cytokine responses in both human lung epithelial and endothelial cells and shows increased human adaptation compared with avian H5N1 virus.

Zeng H1, Belser JA1, Goldsmith CS2, Gustin KM1, Veguilla V1, Katz JM1, Tumpey TM3.

Author information

1

Immunology and Pathogenesis Branch, Influenza Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

2

Infectious Disease Pathology Branch, Division of High Consequence Pathogens and Pathology, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

3

Immunology and Pathogenesis Branch, Influenza Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA tft9@cdc.gov.

Abstract

Similar to H5N1 viruses, A(H7N9) influenza viruses have been associated with severe respiratory disease and fatal outcomes in humans. While high viral load, hypercytokinemia, and pulmonary endothelial cell involvement are known to be hallmarks of H5N1 virus infection, the pathogenic mechanism of the A(H7N9) virus in humans is largely unknown. In this study, we assessed the ability of A(H7N9) virus to infect, replicate, and elicit innate immune responses in both human bronchial epithelial cells and pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells, compared with the abilities of seasonal H3N2, avian H7N9, and H5N1 viruses. In epithelial cells, A(H7N9) virus replicated efficiently but did not elicit robust induction of cytokines like that observed for H5N1 virus. In pulmonary endothelial cells, A(H7N9) virus efficiently initiated infection; however, no released infectious virus was detected. The magnitudes of induction of host cytokine responses were comparable between A(H7N9) and H5N1 virus infection. Additionally, we utilized differentiated human primary bronchial and tracheal epithelial cells to investigate cellular tropism using transmission electron microscopy and the impact of temperature on virus replication. Interestingly, A(H7N9) virus budded from the surfaces of both ciliated and mucin-secretory cells. Furthermore, A(H7N9) virus replicated to a significantly higher titer at 37 °C than at 33 °C, with improved replication capacity at 33 °C compared to that of H5N1 virus. These findings suggest that a high viral load from lung epithelial cells coupled with induction of host responses in endothelial cells may contribute to the severe pulmonary disease observed following H7N9 virus infection. Improved adaptation of A(H7N9) virus to human upper airway poses an important threat to public health.

IMPORTANCE:

A(H7N9) influenza viruses have caused over 450 documented human infections with a 30% fatality rate since early 2013. However, these novel viruses lack many molecular determinants previously identified with mammalian pathogenicity, necessitating a closer examination of how these viruses elicit host responses which could be detrimental. This study provides greater insight into the interaction of this virus with host lung epithelial cells and endothelial cells, which results in high viral load, epithelial cell death, and elevated immune response in the lungs, revealing the mechanism of pathogenesis and disease development among A(H7N9)-infected patients. In particular, we characterized the involvement of pulmonary endothelial cells, a cell type in the human lung accessible to influenza virus following damage of the epithelial monolayer, and its potential role in the development of severe pneumonia caused by A(H7N9) infection in humans.

Copyright © 2015, American Society for Microbiology. All Rights Reserved.A(H7N9) virus results in early induction of proinflammatory cytokine responses in both human lung epithelial and endothelial cells and shows increa... - PubMed - NCBI

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25673714

HARVARD EALTH & MEDICINE

Study confirms vitamin D protects against colds and flu

A recent study by a global team of researchers has found that Vitamin D supplements, already widely prescribed for a variety of ailments, are effective in preventing respiratory diseases.

A new global collaborative study has confirmed that vitamin D supplementation can help protect against acute respiratory infections. The study, a participant data meta-analysis of 25 randomized controlled trials including more than 11,000 participants, has been published online in The BMJ.

“Most people understand that vitamin D is critical for bone and muscle health,” said Carlos Camargo of the Department of Emergency Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), the study’s senior author. “Our analysis has also found that it helps the body fight acute respiratory infection, which is responsible for millions of deaths globally each year.”

Several observational studies, which track participants over time without assigning a specific treatment, have associated low vitamin D levels with greater susceptibility to acute respiratory infections. A number of clinical trials have been conducted to investigate the protective ability of vitamin D supplementation, but while some found a protective effect, others did not. Meta-analyses of these trials, which aggregate data from several studies that may have different designs or participant qualifications, also had conflicting results.

To resolve these discrepancies, the research team — led by Adrian Martineau from Queen Mary University of London — conducted an individual participant data meta-analysis of trials in more than a dozen countries, including the U.S., Canada, and the U.K. While traditional meta-analyses compare average data from all participants in each study, individual participant data meta-analysis separates out the data from each individual participant, producing what could be considered a higher-resolution analysis of the data from all studies.

The investigators found that daily or weekly supplementation had the greatest benefit for individuals with the most significant vitamin D deficiency (blood levels below 10 mg/dl) — cutting their risk of respiratory infection in half — and that all participants experienced some beneficial effects from regular vitamin D supplementation. Administering occasional high doses of vitamin D did not produce significant benefits.

“Acute respiratory infections are responsible for millions of emergency department visits in the United States,” said Camargo, who is a professor of emergency medicine at Harvard Medical School. “These results could have a major impact on our health system and also support efforts to fortify foods with vitamin D, especially in populations with high levels of vitamin D deficiency.”

The study was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Health Research (U.K.).

哈佛医学院

研究证实维生素D可预防感冒和流感

由全球研究人员组成的团队最近进行的一项研究发现,维生素D补充剂已被广泛用于多种疾病,可有效预防呼吸道疾病。

一项全球合作研究表明,补充维生素D有助于预防急性呼吸道感染。该研究是一项包括25个随机对照试验的参与者数据荟萃分析,其中包括11,000多名参与者,已在线发表在BMJ上。

该研究的资深作者,麻省总医院(MGH)急诊科的卡洛斯·卡玛戈(Carlos Camargo)说:“大多数人都知道维生素D对骨骼和肌肉健康至关重要。” “我们的分析还发现,它可以帮助人体抵抗急性呼吸道感染,而这种疾病每年在全球造成数百万人死亡。”

几项观察性研究随时间推移追踪参与者而未分配具体治疗方法,这些研究发现维生素D含量低与急性呼吸道感染的易感性有关。已经进行了许多临床试验来研究补充维生素D的保健作用,但是尽管一些发现了保护作用,但其他人却没有。这些试验的荟萃分析汇总了一些研究的数据,这些研究可能具有不同的设计或参加者资格,但结果也不一致。为解决这些差异,由伦敦玛丽大学(Queen Mary University of London)的阿德里安·马丁诺(Adrian Martineau)领导的研究小组在包括美国,加拿大和英国在内的十几个国家/地区对试验的参与者数据进行了荟萃分析,而传统的分析会比较每个研究中所有参与者的平均数据,个体参与者数据荟萃分析会从每个个体参与者中分离出数据,从而可以对所有研究的数据进行更高分辨率的分析。

研究人员发现,每天或每周补充维生素D对维生素D缺乏症最严重的人(血液水平低于10 mg / dl)具有最大的益处-将其呼吸道感染的风险降低了一半-并且所有参与者都从常规补充维生素D中获得益处。偶尔服用大剂量维生素D并没有产生明显的益处。

哈佛医学院的急诊医学教授卡玛戈说:“急性呼吸道感染导致美国数百万急诊就诊。” “这些结果可能会对我们的卫生系统产生重大影响,并且还支持努力强化含维生素D的食品,特别是在维生素D缺乏水平高的人群中。”

该研究由英国国立卫生研究院(National Institute of Health Research)资助。Study confirms vitamin D protects against colds and flu – Harvard Gazette

https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2017/02/study-confirms-vitamin-d-protects-against-cold-and-flu/

7.12: Virus Replication

Last updatedJun 15, 2019

7.11: Discovery and Origin of Viruses

7.13: Viruses and Human Disease

Notice the viruses sitting on the bacteria?

Why is the virus sitting here? Remember, viruses are not living. So how do they replicate?

Replication of Viruses

Populations of viruses do not grow through cell division because they are not cells. Instead, they use the machinery and metabolism of a host cell to produce new copies of themselves. After infecting a host cell, a virion uses the cell’s ribosomes, enzymes, ATP, and other components to replicate. Viruses vary in how they do this. For example:

Some RNA viruses are translated directly into viral proteins in ribosomes of the host cell. The host ribosomes treat the viral RNA as though it were the host’s own mRNA.

Some DNA viruses are first transcribed in the host cell into viral mRNA. Then the viral mRNA is translated by host cell ribosomes into viral proteins.

In either case, the newly made viral proteins assemble to form new virions. The virions may then direct the production of an enzyme that breaks down the host cell wall. This allows the virions to burst out of the cell. The host cell is destroyed in the process. The newly released virus particles are free to infect other cells of the host.

Replication of RNA Viruses

An RNA virus is a virus that has RNA as its genetic material. Their nucleic acid is usually single-stranded RNA, but may be double-stranded RNA. Important human pathogenic RNA viruses include the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) virus, Influenza virus, and Hepatitis C virus. Animal RNA viruses can be placed into different groups depending on their type of replication.

Some RNA viruses have their genome used directly as if it were mRNA. The viral RNA is translated directly into new viral proteins after infection by the virus.

Some RNA viruses carry enzymes which allow their RNA genome to act as a template for the host cell to a form viral mRNA.

Retroviruses use DNA intermediates to replicate. Reverse transcriptase, a viral enzyme that comes from the virus itself, converts the viral RNA into a complementary strand of DNA, which is copied to produce a double stranded molecule of viral DNA. This viral DNA is then transcribed and translated by the host machinery, directing the formation of new virions. Normal transcription involves the synthesis of RNA from DNA; hence, reverse transcription is the reverse of this process. This is an exception to the central dogma of molecular biology.

Replication of DNA Viruses

A DNA virus is a virus that has DNA as its genetic material and replicates using a DNA-dependent DNA polymerase. The nucleic acid is usually double-stranded DNA but may also be single-stranded DNA. The DNA of DNA viruses is transcribed into mRNA by the host cell. The viral mRNA is then translated into viral proteins. These viral proteins then assemble to form new viral particles.

Reverse-Transcribing Viruses

A reverse-transcribing virus is any virus which replicates using reverse transcription, the formation of DNA from an RNA template. Some reverse-transcribing viruses have genomes made of single-stranded RNA and use a DNA intermediate to replicate. Others in this group have genomes that have double-stranded DNA and use an RNA intermediate during genome replication. The retroviruses, as mentioned above, are included in this group, of which HIV is a member. Some double-stranded DNA viruses replicate using reverse transcriptase. The hepatitis B virus is one of these viruses.

Bacteriophages are viruses that infect bacteria. They bind to surface receptor molecules of the bacterial cell and then their genome enters the cell. The protein coat does not enter the bacteria. Within a short amount of time, in some cases, just minutes, bacterial polymerase starts translating viral mRNA into protein. These proteins go on to become either new virions within the cell, helper proteins which help assembly of new virions, or proteins involved in cell lysis. Viral enzymes aid in the breakdown of the cell membrane. With some phages, just over twenty minutes after the phage infects the bacterium, over three hundred phages can be assembled and released from the host.

为什么新型冠状病毒在人体内复制这么快?

新型冠状病毒是一种RNA病毒。

RNA病毒复制

RNA病毒是一种以RNA为遗传物质的病毒。它们的核酸通常是单链RNA,但也可能是双链RNA。重要的人类致病性RNA病毒包括严重急性呼吸系统综合症(SARS)病毒和新型冠状病毒,流感病毒和丙型肝炎病毒。根据其复制类型,可以将动物RNA病毒分为不同的组。

有些RNA病毒的基因组直接用作mRNA。病毒感染后,病毒RNA可直接翻译成新的病毒蛋白。

一些RNA病毒携带的酶允许其RNA基因组充当宿主细胞形成病毒mRNA的模板。

逆转录病毒使用DNA中间体复制。逆转录酶是一种来自病毒本身的病毒酶,可将病毒RNA转化为DNA的互补链,将其复制以产生病毒DNA的双链分子。然后,该病毒DNA被宿主机器转录并翻译,指导新病毒体的形成。正常转录涉及从DNA合成RNA。因此,逆转录是该过程的逆过程。这是分子生物学中心教条的一个例外。7.12: Virus Replication - Biology LibreTexts

https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/Book%3A_Introductory_Biology_(CK-12)/7%3A_Prokaryotes_and_Viruses/7.12%3A_Virus_Replication

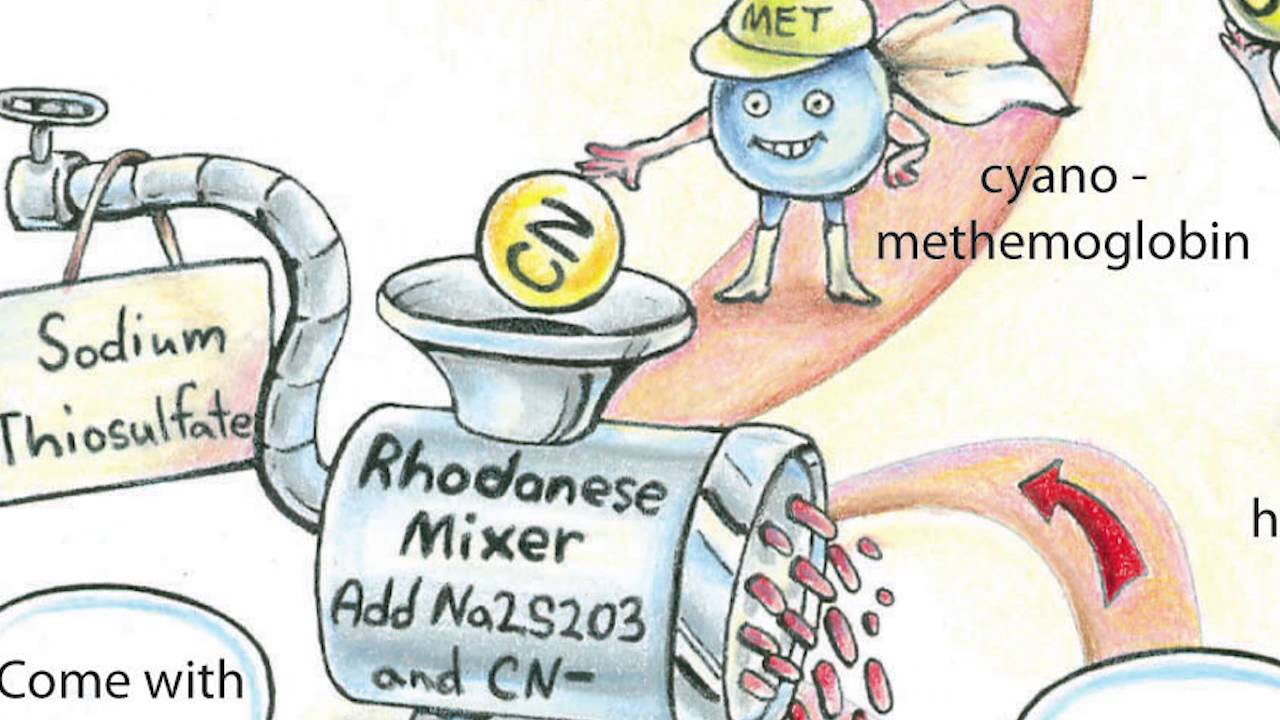

Lopinavir罗匹那韦

蛋白酶抑制剂,抗逆转录病毒。

洛匹那韦的作用机理

罗匹那韦是肽类似物。它可逆地结合到HIV编码的天冬氨酰蛋白酶的催化位点,该酶参与多蛋白降解成结构蛋白和随后的病毒颗粒成熟。洛匹那韦与酶的结合导致非感染性病毒后代。

洛匹那韦的药代动力学

吸收:口服吸收

分布:主要以蛋白质结合形式分布

代谢:它在肝脏中进行新陈代谢。

排泄:药物及其代谢物主要通过粪便排出。Ritonavir

About Ritonavir

HIV Protease Inhibitor, Thiazole derivative, Antiretroviral.

Mechanism of Action of Ritonavir

Ritonavir is a peptide analogue. It reversibly binds to the catalytic site of HIV encoded aspartyl protease enzyme which is involved in the degradation of poly protein into structural protein and subsequent maturation of virus particle. Binding of Ritonavir to the enzyme results in immature noninfectious viral progeny

Pharmacokinets of Ritonavir

Absorption: It is rapidly absorbed after oral administration. Distribution: It is distributed as protein bound form. Metabolism: It undergoes metabolism in the liver. Excretion: It is excreted primarily through faeces and small amount through urineRitonavir利托那韦

HIV蛋白酶抑制剂,噻唑衍生物,抗逆转录病毒。

利托那韦的作用机理

利托那韦是肽类似物。它可逆地结合到HIV编码的天冬氨酰蛋白酶的催化位点,该酶参与多蛋白降解成结构蛋白和随后的病毒颗粒成熟。利托那韦与酶的结合导致非感染性病毒后代

利托那韦的药代动力学

吸收:口服后迅速吸收。分布:它以蛋白质结合形式分布。代谢:它在肝脏中进行新陈代谢。排泄:主要通过粪便排出,少量通过尿排出

新型冠状病毒感染肺炎疫情时期的合理营养与膳食建议

发布时间:2020-02-03

张立实

四川大学华西公共卫生学院 教授/博士生导师

中国营养学会常务理事/四川省营养学会理事长

大家都已经知道,对于新型冠状病毒感染肺炎,目前还没有特异性的疫苗和治疗药物。这种传染性疾病的发生、发展与预后(死亡或康复),很大程度上取决于个体的免疫功能及其营养、健康状况(如:是否有营养不良或营养失衡,是否患有慢性非传染性疾病,体质情况等)。因此,通过合理膳食来增强机体的免疫功能和身体素质,提高抗病能力,对预防新型冠状病毒感染肺炎的发生或减轻其病情有非常重要的意义。

在此,对新型冠状病毒感染肺炎疫情时期一般人群(不包括新型冠状病毒感染肺炎患者和疑似患者、疫情一线的医务工作者和其他人员,以及其他疾病患者等)的合理营养与膳食给出以下几点简明扼要的建议:

1. 重视食物多样化,尽量做到膳食平衡

每天尽可能在各大类食物(谷薯类、蔬菜水果类、奶蛋类、禽畜肉和鱼虾类、大豆坚果类)中选择多种食物,以满足人体基本的营养需求和平衡膳食的需要。同时,由于活动和运动减少,应适当控制总能量和高脂肪食物(肥肉、动植物油脂、油炸食品等)的摄入,以“食至七、八分饱”和维持健康体重为宜。

2. 保证蛋白质,尤其是优质蛋白质的足量摄入

蛋白质是构成人体组织细胞的主要成分,具有多方面的重要生理作用,尤其对于维持机体的正常免疫功能、防御病毒感染有至关重要的作用。因此,要保证每天摄入充足的蛋白质,尤其是优质蛋白质。富含优质蛋白质的食物包括瘦肉、鱼、虾、蛋、奶和大豆(制品)等,每日摄入瘦肉和鱼虾类应不少于100g,并尽量保证每天吃一个鸡蛋;奶类、大豆(制品)和坚果类等也可适当多选择食用。

3. 适量多吃新鲜蔬菜和水果

新鲜蔬菜水果中富含维生素类(尤其是维生素C)、矿物质和微量元素、有机酸以及多种多样的植物化学物(如黄酮类、多酚类、多糖类、花青素和类胡萝卜素、含硫化合物、皂苷类等),具有不同程度的增强免疫力和抗氧化等作用,对防御病毒感染有一定益处。建议每天选择食用至少4~5种蔬菜(其中深色蔬菜不少于一半),2~3种水果,蔬果总量应不少于500克。如因食物供应和购买方面等客观原因不能充分保证新鲜蔬果的种类和数量,可选择适量的干菜干果加以补充。菌菇类富含香菇多糖等具有增强免疫功能的化合物,可适量多吃。大蒜、洋葱、葱等辛辣味重的蔬菜含有较多的含硫化合物,可提高体内免疫细胞的活力,也有预防病毒感染的作用,亦可适量食用。

4. 重视食品安全

非常时期尤其要重视食品安全,避免因食品卫生问题而发生食物中毒和其他食源性疾病;不要购买和食用野生动物,以及某些平常没有吃过或很少食用的食物;食物准备和烹饪、制作者更要注意个人卫生,勤洗手,并保证“生熟分开”操作;尽量少吃生冷食物,尤其动物性食物要烧熟煮透再吃;尽量不要外出聚餐,家庭用餐也建议使用分餐制或使用公勺公筷等,尤其对于“在家隔离”的情况,更要十分重视分开就餐以及食物和就餐环境的卫生。

5. 保证充足的饮水量

足量的水是维持人体内物质代谢和正常生理功能(包括免疫功能)所必需,故应保证每日有充足的饮水量。不同个体的水代谢和饮水习惯常有较大差异,应在平常饮水量的基础上略有增加,一般每天应不少于2000ml(约5大茶杯),并建议多饮白开水或茶水,尽量少喝高糖饮料和碳酸饮料。

6.适当补充维生素和保健食品

在食物供应和种类、数量有限,或特殊健康原因(如免疫力低下、微量营养素缺乏或需要量增加)等情况下,可选择服用复合维生素矿物质补充剂和具有增强免疫力功能的保健食品。

7. 保持适当的运动/活动量和良好的心态

因疫情防控需要而尽可能少外出,更多时间是“宅家”,在这种情况下,更应重视保持良好的心态,相信科学,相信党和政府,对战胜疫情要有足够的信心。同时,要注意每天保持一定的运动/活动量,视不同的居家环境条件和个人爱好,进行适当的室内运动/活动;在条件允许的情况下,也可到空旷人少的地方(如公园、校园等)进行适当的户外活动。https://www.cnsoc.org/learnnews/322000201.html

Human Beta Defensin 2 Selectively Inhibits HIV-1 in Highly Permissive CCR6+CD4+ T Cells

by Mark K. Lafferty 1,2, Lingling Sun 1, Aaron Christensen-Quick 1,2, Wuyuan Lu 1,3 and Alfredo Garzino-Demo 1,2,4,*OrcID

1

Division of Basic Science, Institute of Human Virology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA

2

Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA

3

Department of Biochemistry, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA

4

Department of Molecular Medicine, University of Padova, Padova 35121, Italy

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Academic Editor: Theresa Chang

Viruses 2017, 9(5), 111; https://doi.org/10.3390/v9050111

Abstract

Chemokine receptor type 6 (CCR6)+CD4+ T cells are preferentially infected and depleted during HIV disease progression, but are preserved in non-progressors. CCR6 is expressed on a heterogeneous population of memory CD4+ T cells that are critical to mucosal immunity. Preferential infection of these cells is associated, in part, with high surface expression of CCR5, CXCR4, and α4β7. In addition, CCR6+CD4+ T cells harbor elevated levels of integrated viral DNA and high levels of proliferation markers.

We have previously shown that the CCR6 ligands MIP-3α and human beta defensins inhibit HIV replication. The inhibition required CCR6 and the induction of APOBEC3G. Here, we further characterize the induction of apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme (APOBEC3G) by human beta defensin 2. Human beta defensin 2 rapidly induces transcriptional induction of APOBEC3G that involves extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 (ERK1/2) activation and the transcription factors NFATc2, NFATc1, and IRF4.

We demonstrate that human beta defensin 2 selectively protects primary CCR6+CD4+ T cells infected with HIV-1. The selective protection of CCR6+CD4+ T cell subsets may be critical in maintaining mucosal immune function and preventing disease progression. View Full-Text

人类β防御素2选择性抑制高度允许的CCR6 + CD4 + T细胞中的HIV-1。抽象

6型趋化因子受体(CCR6)+ CD4 + T细胞在HIV疾病发展过程中会优先受到感染和消耗,但保留在非进展者中。 CCR6在对黏膜免疫至关重要的记忆CD4 + T细胞异质群体中表达。这些细胞的优先感染部分与CCR5,CXCR4和α4β7的高表面表达有关。此外,CCR6 + CD4 + T细胞具有较高水平的整合病毒DNA和高水平的增殖标记物。 先前我们已经表明,CCR6配体MIP-3α和人β防御素可抑制HIV复制。抑制作用需要CCR6和APOBEC3G的诱导。在这里,我们进一步表征了人类β防御素2对载脂蛋白B mRNA编辑酶(APOBEC3G)的诱导。人类β防御素2快速诱导APOBEC3G的转录诱导,涉及细胞外信号调节激酶1/2(ERK1 / 2)激活和转录因子NFATc2,NFATc1和IRF4。我们证明了人类β防御素2选择性保护感染了HIV-1的初级CCR6 + CD4 + T细胞。 CCR6 + CD4 + T细胞亚群的选择性保护对于维持粘膜免疫功能和预防疾病进展可能至关重要。

Viruses | Free Full-Text | Human Beta Defensin 2 Selectively Inhibits HIV-1 in Highly Permissive CCR6+CD4+ T Cells

https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/9/5/111#

Human Beta Defensins and Cancer: Contradictions and Common ...

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6509205

May 03, 2019 · The discovery of human β-defensins (hBDs) in mucosa has led to recognition that they are integral in innate immune protection; shielding mucosal surfaces from microbial challenges.

Cited by: 2

Publish Year: 2019

Author: Santosh K. Ghosh, Thomas S. McCormick, Aaron Weinberg

Fusobacterium nucleatum and Human Beta-Defensins Modulate ...

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3257922

Cells of the innate immune system regulate immune responses through the production of antimicrobial peptides, chemokines, and cytokines, including human beta-defensins (hBDs) and CCL20. In this study, we examined the kinetics of primary human oral epithelial ...

Cited by: 12

Publish Year: 2011

Author: Santosh K. Ghosh, Sanhita Gupta, Bin Jiang, Aaron Weinberg

Production of β-defensins by human airway epithelia | PNAS

https://www.pnas.org/content/95/25/14961.full

Furthermore, it is not known whether β-defensin production is deficient in diseases such as cystic fibrosis (CF) that are characterized by chronic infection. Recent studies have identified β-defensin expression at mucosal surfaces in human tissues, where they may play a role in innate defenses …

Cited by: 736

Publish Year: 1998

Author: Pradeep K. Singh, Hong Peng Jia, Kerry Wiles, Jay Hesselb

Effect of Human Beta Defensin-2 in Epithelial Cell Lines Infected with Respiratory Viruses

Abstract

Miguel Ángel Galván Morales, Alejandro Escobar Gutiérrez, Dora Patricia Rosete Olvera and Carlos Cabello Gutiérrez

β-defensins are a family of antimicrobial molecules involved in inflammatory processes and infections. In human airways, β-defensin-2 (hβD-2) is the best characterized in bacterial and fungal infections; however, it has been insufficiently studied in viral infections. The respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and adenoviruses (ADV) are important agents of acute respiratory infections. The aim of this study was to measure in vitro the production and antiviral activity of hβD-2 in HEp-2 cells and A549 cells infected with ADV and RSV; hβD-2 production at different times was assessed by RT-PCR, and its presence by immunodetection assay (Western blot) using antibodies anti-hβD-2. The effect of this defensin on viral replication was determined using recombinant hβD-2 in plaque assays. The results revealed that in the cell lines production of hβD-2is up regulated after ADV or RSV infection, in direct proportion to the exposure time to each virus. The use of a high concentration of recombinant hβD-2 resulted in less deleterious viral effect on the cells. The results suggest that both viruses induce hβD-2 production, no matter if the virus is enveloped or not, and that presence of hβD-2 reduces replication and cytopathic in vitro effect of RSV and ADV. The hβD-2 production by low pathogenicity viruses or live viral vaccines can be useful as therapeutic tools in some infectious diseases.

人β-防御素-2 (Defensin-2)在呼吸道病毒感染的上皮细胞系中的作用

摘要

MiguelÁngelGalvánMorales,Alejandro EscobarGutiérrez,Dora Patricia Rosete Olvera和Carlos CabelloGutiérrez

β-防御素是涉及炎症过程和感染的一系列抗菌分子。在人的气道中,β-防御素-2(hβD-2)在细菌和真菌感染中表现最出色。但是,在病毒感染方面尚未进行充分的研究。呼吸道合胞病毒(RSV)和腺病毒(ADV)是急性呼吸道感染的重要媒介。这项研究的目的是在体外测量被ADV和RSV感染的HEp-2(人类上皮)细胞和A549细胞中hβD-2的产生和抗病毒活性。通过RT-PCR评估hβD-2在不同时间的产生,并使用抗hβD-2抗体通过免疫检测测定法(Western blot)评估其存在。在噬菌斑试验中使用重组hβD-2确定了这种防御素对病毒复制的作用。

结果表明,在ADV或RSV感染后,hβD-2的生产受到上调,与每种病毒的暴露时间成正比。高浓度重组hβD-2的使用对病毒的细胞有害作用较小。

结果表明,无论是否被包膜病毒,两种病毒均诱导hβD-2的产生,并且hβD-2的存在会降低RSV和ADV的复制和体外细胞病变作用。低致病性病毒或活病毒疫苗产生的hβD-2可用作某些传染病的治疗工具。

Effect of Human Beta Defensin-2 in Epithelial Cell Lines Infected with Respiratory Viruses | Abstract

https://www.hilarispublisher.com/abstract/effect-of-human-beta-defensin2-in-epithelial-cell-lines-infected-with-respiratory-viruses-28005.html

Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1999 Jun;31(6):645-51.

Human beta-defensin-2.

Schröder JM1, Harder J.

1 Department of Dermatology, University of Kiel, Germany. jschroeder@dermatology.uni-kiel.de

Abstract

Human beta-defensin-2 (HBD-2) is a cysteine-rich cationic low molecular weight antimicrobial peptide recently discovered in psoriatic lesional skin. It is produced by a number of epithelial cells and exhibits potent antimicrobial activity against Gram-negative bacteria and Candida, but not Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus. HBD-2 represents the first human defensin that is produced following stimulation of epithelial cells by contact with microorganisms such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa or cytokines such as TNF-alpha and IL-1 beta. The HBD-2 gene and protein are locally expressed in keratinocytes associated with inflammatory skin lesions such as psoriasis as well as in the infected lung epithelia of patients with cystic fibrosis. It is intriguing to speculate that HBD-2 is a dynamic component of the local epithelial defense system of the skin and respiratory tract having a role to protect surfaces from infection, and providing a possible reason why skin and lung infections with Gram-negative bacteria are rather rare.

PMID: 10404637 DOI: 10.1016/s1357-2725(99)00013-8人β-防御素2(HBD-2)是一种最近在银屑病皮损皮肤中发现的富含半胱氨酸的阳离子低分子量抗菌肽。它由许多上皮细胞产生,对革兰氏阴性菌和念珠菌具有有效的抗菌活性,但对革兰氏阳性金黄色葡萄球菌则没有。 HBD-2代表第一个人类防御素,是通过与铜绿假单胞菌等微生物或TNF-α和IL-1β等细胞因子接触刺激上皮细胞而产生的。 HBD-2基因和蛋白在与炎症性皮肤病(如牛皮癣)相关的角质形成细胞中以及在患有囊性纤维化患者的被感染的肺上皮中局部表达。有趣的是,HBD-2是皮肤和呼吸道局部上皮防御系统的动态成分,具有保护表面不受感染的作用,是皮肤和肺部革兰氏阴性细菌感染相当罕见的可能原因。

Human beta-defensin-2. - PubMed - NCBI

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10404637

Human beta-defensin 2 is a salt-sensitive peptide antibiotic expressed in human lung.

R Bals, X Wang, Z Wu, T Freeman, V Bafna, M Zasloff, and J M Wilson

First published September 1, 1998 - More info

Institute for Human Gene Therapy, Department of Medicine and Molecular and Cellular Engineering, The Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, USA.

Abstract

Previous studies have implicated the novel peptide antibiotic human beta-defensin 1 (hBD-1) in the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis. We describe in this report the isolation and characterization of the second member of this defensin family, human beta-defensin 2 (hBD-2). A cDNA for hBD-2 was identified by homology to hBD-1. hBD-2 is expressed diffusely throughout epithelia of many organs, including the lung, where it is found in the surface epithelia and serous cells of the submucosal glands. A specific antibody made of recombinant peptide detected hBD-2 in airway surface fluid of human lung. The fully processed peptide has broad antibacterial activity against many organisms, which is salt sensitive and synergistic with lysozyme and lactoferrin. These data suggest the existence of a family of beta-defensin molecules on mucosal surfaces that in the aggregate contributes to normal host defense.

人β-防御素2是在人肺中表达的盐敏感性肽抗生素。

R Bals,X Wang,Z Z Wu,T Freeman,V Bafna,M Zasloff和J M Wilson

1998年9月1日首次发布-更多信息

美国宾夕法尼亚州费城,维斯塔研究所,医学与分子与细胞工程系,人类基因治疗研究所。

抽象

先前的研究已将新型肽类抗生素人β-防御素1(hBD-1)牵涉到囊性纤维化的发病机理中。我们在这份报告中描述了该防御素家族的第二个成员,人β-防御素2(hBD-2)的分离和鉴定。通过与hBD-1的同源性鉴定了hBD-2的cDNA。hBD-2在包括肺在内的许多器官的上皮中广泛表达,在粘膜下腺的表面上皮和浆液细胞中发现。由重组肽制成的特异性抗体在人肺气道表面液中检测到hBD-2。经过充分加工的肽对多种生物具有广泛的抗菌活性,对盐敏感并与溶菌酶和乳铁蛋白协同作用。这些数据表明,在粘膜表面上存在着一系列的β-防御素分子,这些分子总体上有助于正常的宿主防御。

JCI - Human beta-defensin 2 is a salt-sensitive peptide antibiotic expressed in human lung.

https://www.jci.org/articles/view/2410

Respir Res. 2005; 6(1): 116.

Respiratory epithelial cells require Toll-like receptor 4 for induction of Human β-defensin 2 by Lipopolysaccharide

Ruth MacRedmond,corresponding author1 Catherine Greene,1 Clifford C Taggart,1 Noel McElvaney,1 and Shane O'Neill1

Abstract

Background

The respiratory epithelium is a major portal of entry for pathogens and employs innate defense mechanisms to prevent colonization and infection. Induced expression of human β-defensin 2 (HBD2) represents a direct response by the epithelium to potential infection. Here we provide evidence for the critical role of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced HBD2 expression by human A549 epithelial cells.

Methods

Using RTPCR, fluorescence microscopy, ELISA and luciferase reporter gene assays we quantified interleukin-8, TLR4 and HBD2 expression in unstimulated or agonist-treated A549 and/or HEK293 cells. We also assessed the effect of over expressing wild type and/or mutant TLR4, MyD88 and/or Mal transgenes on LPS-induced HBD2 expression in these cells.

Results

We demonstrate that A549 cells express TLR4 on their surface and respond directly to Pseudomonas LPS with increased HBD2 gene and protein expression. These effects are blocked by a TLR4 neutralizing antibody or functionally inactive TLR4, MyD88 and/or Mal transgenes. We further implicate TLR4 in LPS-induced HBD2 production by demonstrating HBD2 expression in LPS non-responsive HEK293 cells transfected with a TLR4 expression plasmid.

Conclusion

This data defines an additional role for TLR4 in the host defense in the lung.

Keywords: Airway epithelium, Toll-like Receptor 4, Lipopolysaccharide, Human β-defensin 2.

Introduction

The lung represents the largest epithelial surface in the body and is a major portal of entry for pathogenic microorganisms. It employs a number of efficient defense mechanisms to eliminate airborne pathogens encountered in breathing, including the specific innate and adaptive immune responses, which represent a dynamic interaction of host and pathogen. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is an important antigenic component of Gram-negative bacteria, and is a potent stimulus to local and systemic immune responses. The human receptor for LPS is Toll-like-receptor 4 (TLR4) [1].

TLRs are a family of pattern recognition receptors whose pivotal importance in orchestrating the innate immune response is widely accepted. Binding of ligand activates a signaling cascade involving TRAF6, IKKs and I-κBs, culminating in NF-κB translocation to the nucleus [1]. NF-κB regulates the inducible expression of cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules and acute phase proteins which activate cellular immune responses [2]. TLR signaling pathways arise from intracytoplasmic Toll/IL-1 receptor (TIR) domains, which are conserved among TLRs and TIR domain-containing adaptor proteins such as MyD88, Mal/TIRAP and TRIF/TICAM-1. These adaptor proteins confer specificity on TLR signaling, with Mal specifically involved in MyD88-dependent signaling via TLR2 and TLR4, and TRIF in the MyD88-independent TLR3- and TLR4- signaling [3]

The mammalian innate immune system produces a variety of anti-microbial peptides (AMPs) as part of its host defense repertoire. The defensins are a broadly dispersed group of AMPs, and are classified according to their molecular structure into three distinct families: the α-, β- and the θ-defensins. Unlike α-defensins, which are produced mainly by neutrophils, β-defensins are produced directly by epithelial cells, and combat infection both through direct microbicidal action and by modulation of cell-mediated immunity [4-7]. To date, four human β-defensins (HBD) have been identified (HBD1-4), although genomic studies suggest more have yet to be discovered [8,9]. In contrast to HBD1, which is constitutively and stably expressed, HBD2 expression is induced in response to infective stimuli, including Gram-negative and, less potently, Gram-positive bacteria or their components or to proinflammatory stimuli including tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) in vitro [10,11].

Like other defensins, HBD2 has a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity, displaying potent microbicidal activity against many Gram-negative bacteria and less potent bacteriostatic activity against Gram-positive bacteria [11]. It has recently been demonstrated that activation of TLR2 by bacterial lipoprotein results in up regulation of HBD2 in tracheobronchial epithelium [12]. LPS and Gram-negative bacteria such as mucoid P. aeruginosa are a more potent stimulus for HBD2 production, which in turn has anti-bacterial activity predominantly against Gram-negative bacteria. Colonisation and infection due to Gram-negative bacteria are important in many pulmonary diseases including severe COPD [13] and Cystic Fibrosis [14]. Production of HBD2 by respiratory epithelium is an important component of host defense against Gram-negative organisms, and understanding of the signaling pathways involved may further our understanding of and guide future therapeutic strategies in these diseases.

Cultured intestinal epithelial cells have been shown to produce HBD2 in response to LPS following transfection with TLR4 and MD2 [15]. Although CD-14 is known to be critical to LPS-induced HBD2 production in airway epithelium [16], the role of TLR4 in transcriptional regulation of HBD2 in respiratory epithelium has not been established. Indeed, the importance of the respiratory epithelium in the innate immune response to LPS has been called into question by some recent publications [17,18]. In this study we demonstrate TLR4 expression in A549 pulmonary epithelial cells and production of HBD2 in response to LPS. We examine the effect of modulation of TLR4 by receptor blockade and expression of a dominant negative TLR4 construct on induced expression of HBD2. We show that LPS-unresponsive HEK293 cells can produce HBD2 in response to LPS following transfection with TLR4 and MD2 transgenes and demonstrate that the adaptor proteins MyD88 and Mal are involved in transcriptional regulation of HBD2 in response to LPS.Respiratory epithelial cells require Toll-like receptor 4 for induction of Human β-defensin 2 by Lipopolysaccharide

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1276817/

《浙江大学学报(医学版)》 2006年06期

重组β-防御素2多肽对脓毒症大鼠肺组织细胞凋亡的影响

徐笑益 石卓 鲍军明 顾伟忠 姚航平 陈智 高敏 方向明

【摘要】:目的:观察重组β-防御素2多肽预处理对脓毒症大鼠肺组织细胞凋亡的影响。方法:SPF级SD大鼠48只随机分成对照组和防御素组,采用盲肠结扎穿孔术(CLP)复制脓毒症模型,防御素组在CLP前48h经气管插管气道滴注107PFU重组腺病毒(含有β-防御素2编码基因),而对照组则同法给予对照腺病毒(不含β-防御素2编码基因)。分别于CLP后0、12、36和72 h处死大鼠,取肺组织,采用透射电镜,末端脱氧核苷酸转移酶介导的dUTP缺口末端标记法(TUNEL)检测细胞凋亡,采用电镜、苏木精-伊红(HE)染色观察肺组织病理变化。结果:TUNEL检测显示,对照组大鼠CLP后12、36和72 h肺组织细胞凋亡指数显著增加(P0.01);与对照组相比,防御素组CLP后相应时间点肺组织细胞凋亡指数显著降低(P0.05)。HE染色可见,两组大鼠CLP后12、36和72 h肺泡及肺泡间质充血、水肿,炎症细胞渗出,肺泡腔不同程度狭窄。与对照组相比较,防御素组相应时间点肺组织内炎症细胞渗出减少,间质水肿减轻。结论:重组β-防御素2多肽预处理能抑制脓毒症肺组织的细胞凋亡,对急性肺损伤(AL I)具有保护作用。

【作者单位】: 浙江大学医学院附属邵逸夫医院麻醉科 浙江大学医学院附属儿童医院儿科研究所 浙江大学医学院附属邵逸夫医院麻醉科 浙江大学医学院附属儿童医院儿科研究所 浙江大学医学院附属第一医院传染病研究所 浙江大学医学院附属第一医院传染病研究所 浙江大学医学院附属邵逸夫医院临床实验室 浙江大学医学院附属第一医院麻醉科

【基金】:国家自然科学基金资助项目(30070854)

【分类号】:R459.7重组β-防御素-2对呼吸道绿脓杆菌感染大鼠急性肺损伤的保护作用

王海宏 舒强 石卓 赵正言 方向明 【摘要】:目的 观察重组β-防御素-2对呼吸道绿脓杆菌感染大鼠急性肺损伤(ALI)的保护作用。 方法10只清洁级雄性成年SD大鼠,随机分为防御素组和对照组,每组5只。防御素组大鼠暴露声 门后,气管内滴注5×107PFU/ml重组腺病毒(含有β-防御素-2编码基因)50μl,对照组给予等量对照腺 病毒(不含β-防御素-2编码基因)。48 h后两组气管内滴注6×108CFU/ml绿脓杆菌ATCC27853 200μl, 制备绿脓杆菌感染致ALI模型。气管内滴注绿脓杆菌24 h后处死大鼠,采集肺泡灌洗液,进行绿脓杆 菌菌落数和白细胞计数;观察肺组织病理学变化,并测定肺组织细胞间粘附分子-1(ICAM-1)表达水 平。结果与对照组比较,防御素组BALF中绿脓杆菌菌落数、白细胞计数、肺组织ICAM-1表达水平 及肺病理组织学评分降低(P0.05)。结论重组β-防御素-2对呼吸道绿脓杆菌感染大鼠ALI有一 定的保护作用,可能与其杀菌作用和下调肺组织ICAM-1的表达有关。 【作者单位】: 【基金】:国家自然科学基金资助项目(30070854) 【分类号】:R96

《中国呼吸与危重监护杂志》 2010年01期

β-防御素2与下呼吸道感染患者全身炎症反应的关系

刘松 何丽蓉 贺正一 王浩彦

【摘要】:目的研究下呼吸道感染(LRTI)患者外周血β-防御素2(HBD-2)与全身炎症反应的关系。方法LRTI组纳入81例患者,包括社区获得性肺炎、COPD急性加重或(和)合并肺部感染、支气管扩张合并感染。同期20例健康人作为对照组。酶联免疫吸附法(ELISA)测定外周血HBD-2、白细胞介素1β(IL-1β)和IL-8水平。常规进行血细胞分析等实验室检查。比较LRTI组及对照组上述指标的变化。按照采血时患病时间分为7d组、7~14d组和14d组,比较组间差别。对HBD-2与IL-1β、IL-8进行相关分析。结果LRTI组患者外周血HBD-2、IL-1β和白细胞总数(WBC)显著高于对照组(P均0.05)。LRTI患者在患病时间7d组和7~14d组的HBD-2和IL-1β水平均显著高于对照组(P均0.05),14d组患者的HBD-2和IL-1β基本恢复正常(P均0.05)。不同患病时间的LRTI患者IL-8水平无显著差异(P均0.05)。外周血HBD-2与IL-1β呈显著正相关(r=0.313,P=0.030);HBD-2与IL-8无显著相关性(P0.05)。结论LRTI患者外周血HBD-2明显升高,HBD-2升高主要表现在疾病早期或相对早期。外周血HBD-2升高可能与全身炎症反应有关。

【作者单位】: 首都医科大学附属北京友谊医院呼吸内科;

In this study, bovine lactoferrin (bLF) was used in both in vitro and in vivo approaches to investigate its activity against lung cancer. A human lung cancer cell line, A549, which expresses a high level of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) under hypoxia, was used as an in vitro system for bLF treatment.

Bovine lactoferrin inhibits lung cancer growth through ...

www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022030213001434

Tips for healthy respiratory system

People often take healthy respiratory system for granted as breathing happens almost automatically. However, by taking proper measures one can increase the health of the respiratory system.

LUNG DISEASES By : Meenakshi Chaudhary , Onlymyhealth Editorial Team / Date : Jan 25, 2014

RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

People often take healthy respiratory system for granted as breathing happens almost automatically. But the fact that even a slight decrease in the lung function cannot be ignored as it can cause disorder to the rest of the body declining your overall health. However, by taking proper measures one can increase the health of the respiratory system.

EAT HEALTHY

Healthy eating is important to maintain the health of your lungs. Our body needs vitamins and nutrients to work effectively and build the tissues including the ones that make up the respiratory system. According to some studies, healthy fats such as omega-3 fatty acids help in inhibiting the inflammation in the lungs and provide an ameliorative effect to the asthma patients.

QUIT SMOKING

If you are a smoker, one of the most important changes that can be made to improve the respiratory health is stop smoking. Tar and thousands of chemicals of the cigarette smoke tend to reduce the capacity and efficiency of your lungs. Long term smoking can result in irreversible chronic respiratory problems. Quitting smoking not only helps in reversing the acute health problems but helps in improving the respiratory health.

EXERCISE

Regular aerobic exercise can help you improve the respiratory health. Exercise increases need of oxygen to your muscles causing the brain to stimulate the respiratory system to increase ventilation or breathing. This increase in the frequency and depth of breathing expands your lungs, enhances the elasticity of the air sacs, expels old air within your lungs and tones and strengthens the diaphragm. All these changes have a lasting effect which helps in improving respiratory health even after you have stopped exercising.

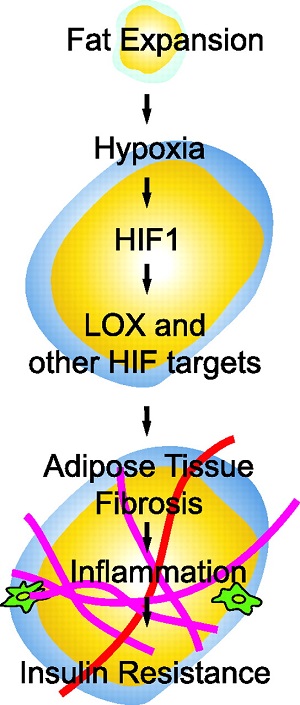

OBESITY

Obesity is a result of bad eating and lifestyle habits which may have bad effects on your respiratory system. A low cholesterol diet is good for your overall health while a diet rich in refined sugars and trans fats will contribute to poor respiratory system.

AVOID POLLUTION

Pollution and urban smog can cause respiratory problems like asthma, bronchitis and lung cancer. If you live in a large city, wearing a face mask will act as a protective barrier to your respiratory system.

FAST FOOD

Fast food can increase your chances of having a respiratory disease. Switch to a healthy diet for a strong respiratory system. Food like dairy may also harm your respiration. Consuming dairy can trigger asthma attacks and contribute to the general poor health of the respiratory system. So keep a check on your fast food and dairy intake.

SLEEP

Several studies have shown that people who get an extra hour of sleep at night have a lower risk for respiratory problems and artery-clogging calcification that can lead to heart disease. People who don't get enough sleep are more prone to respiratory problems.

ALCOHOL

Alcohol consumption can lead to high blood pressure which can lead to respiratory problems and heart failure. Anything more than moderate intake of alcohol may be harmful to your overall health.

AVOID ALLERGENS

Common allergens like dust mites, pollen, mold, and animal dander can be harmful for your respiratory system. Vacuum and damp dust all surfaces regularly. Ensure that your ac filters, curtains and carpet is regularly cleaned with similar chemical solutions.

促进呼吸系统健康的提示

人们常常认为健康的呼吸系统是理所当然的,因为呼吸几乎是自动发生的。但是,通过采取适当的措施,可以提高呼吸系统的健康。

肺部疾病作者:Meenakshi Chaudhary,Onlymyhealth编辑部团队/日期:2014年1月25日

呼吸系统

人们常常认为健康的呼吸系统是理所当然的,因为呼吸几乎是自动发生的。但是,即使肺功能略有下降,这一事实也不容忽视,因为它可能导致身体其他部位的不适,从而影响您的整体健康。但是,通过采取适当的措施,可以提高呼吸系统的健康。

吃得健康

健康饮食对维持肺部健康至关重要。我们的身体需要维生素和营养素才能有效发挥作用,并建立包括构成呼吸系统的组织在内的组织。根据一些研究,诸如omega-3脂肪酸(亚麻酸、EPA,DHA)之类的健康脂肪有助于抑制肺部炎症,并为哮喘患者提供改善作用。

戒烟

如果您是吸烟者,那么可以改善呼吸系统健康的最重要的改变之一就是戒烟。香烟烟雾中的焦油和数千种化学物质往往会降低肺部的容量和效率。长期吸烟会导致不可逆的慢性呼吸问题。戒烟不仅有助于扭转急性健康问题,而且有助于改善呼吸系统健康。

运动

定期进行有氧运动可以帮助您改善呼吸健康。运动会增加肌肉对氧气的需求,导致大脑刺激呼吸系统,从而增加通风或呼吸。呼吸频率和呼吸深度的增加可扩展您的肺部,增强肺泡的弹性,排出肺部的旧空气,并增强隔膜。所有这些变化都具有持久作用,即使您停止运动后也可以帮助改善呼吸健康。

肥胖

肥胖是不良饮食和生活方式的结果,可能对呼吸系统造成不良影响。低胆固醇饮食对您的整体健康有益,而富含精制糖和反式脂肪的饮食会导致呼吸系统不良。

避免污染污染和城市烟雾可导致呼吸系统疾病,如哮喘,支气管炎和肺癌。如果您生活在大城市中,则戴上口罩会成为呼吸系统的防护屏障。

快餐

快餐可以增加您患呼吸系统疾病的机会。改用健康饮食以增强呼吸系统。

睡觉

几项研究表明,晚上多睡一小时的人患呼吸系统疾病和动脉阻塞钙化的风险较低,可导致心脏病。睡眠不足的人更容易出现呼吸系统问题。

酒精

喝酒会导致高血压,从而导致呼吸系统问题和心力衰竭。过量摄入酒精可能对您的整体健康有害。

避免过敏原

常见的过敏原,如尘螨,花粉,霉菌和动物皮屑,可能对呼吸系统有害。定期对所有表面进行真空吸尘。确保使用类似化学溶液定期清洁交流滤波器,窗帘和地毯。Tips for healthy respiratory system | Lung Diseases

https://www.onlymyhealth.com/health-slideshow/tips-for-healthy-respiratory-system-1390564565.html

Adv Pharm Bull. 2014 Dec; 4(Suppl 2): 555–561.

The Effect of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on ARDS: A Randomized Double-Blind Study

Masoud Parish, 1 Farnaz Valiyi, 1 Hadi Hamishehkar, 2 Sarvin Sanaie, 3 Mohammad Asghari Jafarabadi, 4 Samad EJ Golzari, 5 and Ata Mahmoodpoor 1 ,*

1 Faculty of Medicine, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

2 Applied Drug Research Center, Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

3 Tuberculosis & Lung Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

4 Road Traffic Injury Research Center, Faculty of Health, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

5 Cardiovascular Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

Abstract

Purpose: The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of an enteral nutrition diet, enriched with omega-3 fatty acids because of its anti-inflammatory effects on treatment of patients with mild to moderate ARDS.

Methods: This randomized clinical trial was performed in two ICUs of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences from Jun 2011 until Sep 2013 in north west of Iran. Fifty-eight patients with mild to moderate ARDS were enroled in this clinical trial. All patients received standard treatment for ARDS based on ARDS network trial. In intervention group, patients received 6 soft-gels of omega-3/day in addition to the standard treatment.

Results: Tidal volume, PEEP, pH, PaO2/FiO2 , SaO2, P platue and PaCO2 on the 7th and 14th days didn’t have significant difference between two groups. Indices of lung mechanics (Resistance, Compliance) had significant difference between the groups on the 14th day. Pao2 had significant difference between two groups on both 7th and 14th days. Trend of PaO2 changes during the study period in two groups were significant. We showed that adjusted mortality rate did not have significant difference between two groups.

Conclusion: It seems that adding omega-3 fatty acids to enteral diet of patients with ARDS has positive results in term of ventilator free days, oxygenation, lung mechanic indices; however, we need more multi center trials with large sample size and different doses of omega-3 fatty acids for their routine usage as an adjuant for ARDS treatment.

Keywords: ARDS, Inflammation, Omega-3 fatty acids, ICUThe Effect of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on ARDS: A Randomized Double-Blind Study

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4312405/

Lung Compliance and Elastance | Owlcation

https://owlcation.com/stem/Lung-Compliance-and-Elastance

The ability of the lungs to expand is expressed using a measure known as the lung compliance. Lung compliance is the volume change that could be achieved in the lungs per unit pressure change. Elastance, also known as the elastic resistance is the reciprocal of compliance, i.e. the pressure change that is required to elicit a unit volume change. This is a measure of the resistance of a system to expand.

Published: Jul 29, 2013What’s The Difference Between Oxygen Saturation And PaO2?

https://airwayjedi.com/2015/12/09/difference-oxygen-saturation-pao2

Pa02, put simply, is a measurement of the actual oxygen content in arterial blood. Partial pressure refers to the pressure exerted on the container walls by a specific gas in a mixture of other gases. When dealing with gases dissolved in liquids like oxygen in blood, partial pressure is the pressure that the dissolved gas would have if the blood were allowed to equilibrate with a volume of gas in a container. In other words, if a gas like oxygen is present in an air space like the lungs and also dissolved in a liquid like blood, and th…

Partial Pressure of Oxygen (PaO2) Test: Uses, Procedure ...

https://www.verywellhealth.com/partial-pressure-of-oyxgen-pa02-914920

Nov 19, 2019 · The partial pressure of oxygen, also known as PaO2, is a measurement of oxygen pressure in arterial blood. It reflects how well oxygen is able to move from the lungs to the blood, and it …

Omega 3 Fatty Acids May Reduce Bacterial Lung Infections Associated with COPD

Tuesday, March 15, 2016

Compounds derived from omega-3 fatty acids – like those found in salmon – might be the key to helping the body combat lung infections, according to researchers at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry.

The omega-3 derivatives were effective at clearing a type of bacteria called Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi), which often plagues people with inflammatory diseases like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

COPD, which is most often caused by years of smoking, is characterized by inflammation and excessive mucus in the lungs that blocks airflow. Quitting can slow the progress of COPD, but it doesn’t halt the disease. Anti-inflammatory drugs are the most common treatment, however they suppress the immune system, which can put people with COPD at risk for secondary infections, most commonly NTHi bacterial infections.

Our biggest concern with patients who have COPD is bacterial infections, which often put their lives at risk. If we can figure out how to predict who is likely to get an infection, physicians could put them on a preventative medication.

“Our biggest concern with patients who have COPD is bacterial infections, which often put their lives at risk,” says Richard Phipps, Ph.D. professor of Environmental Medicine and director of the URSMD Lung Biology and Disease Program. “If we can figure out how to predict who is likely to get an infection, physicians could put them on a preventative medication.”

In his recent study, which was featured in the top ten percent of the March 15 issue of The Journal of Immunology, Phipps and lead author, Amanda Croasdell, a graduate student in the Toxicology program, tested the effectiveness of an inhalable omega-3 derivative to prevent NTHi lung infections in mice.

Omega-3 fatty acids, which are abundant in fish like sardines and salmon, are touted for their many health benefits. These superstars of the diet world are normally broken down to form molecules that help turn off inflammation after an infection or injury.

Richard Phipps, Ph.D.

“We never really knew why diets high in omega fatty acids seemed good, but now we know it’s because they provide the precursors for molecules that help shut down excessive inflammation.” says Phipps.

Doctors used to believe that shutting down inflammation only required removing whatever caused it, for example pulling a thorn from your finger or, in this case, getting rid of bacteria. While that might work some of the time, we now know that shutting down inflammation is an active process that requires a certain class of anti-inflammatory molecules.

Unlike other anti-inflammatory drugs, the specialized agent used in this study reduced inflammation in the lungs of mice without suppressing the ability to clear the bacteria. In fact, it could actually hasten the process of clearing bacteria. Phipps and his colleagues believe they are the first to show that this special compound can improve lung function in the face of live bacteria.

While these results are encouraging, further study is needed to understand how these compounds can be used in humans. A similar compound in the form of an eye drop solution was recently tested in a clinical trial for dry eye syndrome and was well tolerated.

If found to be effective in humans, the agent used in this study might have the potential to improve the lives of the millions of people around the world who suffer from COPD, and might also be used to treat ear infections, bronchitis, and pneumonia, which are also caused by NTHi.

###

The University of Rochester Medical Center is home to approximately 3,000 individuals who conduct research on everything from cancer and heart disease to Parkinson’s, pandemic influenza, and autism. Spread across many centers, institutes, and labs, our scientists have developed therapies that have improved human health locally, in the region, and across the globe. To learn more, visit http://www.urmc.rochester.edu/research.

欧米茄3脂肪酸可减少与COPD相关的细菌性肺部感染

2016年3月15日星期二

罗彻斯特大学医学中心(University of Rochester Medical Center)大约有3,000人,从事从癌症和心脏病到帕金森氏病,大流行性流感和自闭症的各种研究。我们的科学家分布在许多中心,研究所和实验室中,其开发的疗法改善了当地,该地区以及全球的人类健康。要了解更多信息,请访问http://www.urmc.rochester.edu/research。

欧米茄3脂肪酸可以减少与COPD相关的细菌性肺部感染-新闻室-罗切斯特大学医学中心

罗切斯特大学医学院(Rochester University of Medicine and Dentistry)的研究人员称,源自omega-3脂肪酸的化合物(如鲑鱼中的那些化合物)可能是帮助机体抵抗肺部感染的关键。

omega-3衍生物可有效清除一种称为非典型流感嗜血杆菌(NTHi)的细菌,这种细菌经常困扰患有慢性阻塞性肺疾病(COPD)等炎性疾病的人。

COPD(慢性阻塞性肺病)最常由多年吸烟引起,其特征是炎症和肺部粘液过多阻止气流。戒烟可以减慢COPD的进程,但并不能阻止这种疾病。抗炎药是最常见的治疗方法,但是它们会抑制免疫系统,使COPD患者处于继发感染(最常见的是NTHi细菌感染)的风险中。

对于患有COPD的患者,我们最大的担忧是细菌感染,这常常使他们的生命处于危险之中。如果我们能弄清楚如何预测谁可能感染,医生可以将其放在预防药物上。

“我们对患有COPD的患者最大的担忧是细菌感染,这常常使他们的生命处于危险之中,”理查德·菲普斯(Richard Phipps)博士说。他是环境医学教授,URSMD肺部生物与疾病计划主任。 “如果我们能弄清楚如何预测谁可能感染,医生可以将它们放在预防药物上。”

在他最近发表在3月15日出版的《免疫学杂志》中排名前十位的研究中,Phipps和主要作者Amanda Croasdell,毒理学项目的研究生,测试了可吸入omega-3衍生物的有效性预防小鼠的NTHi肺部感染。

鱼,沙丁鱼和鲑鱼中富含的Omega-3脂肪酸因其许多健康益处而受到吹捧。这些饮食界的超级巨星通常会分解形成有助于感染或受伤后关闭炎症的分子。

Phipps说:“我们从来不真正知道为什么富含欧米茄-3脂肪酸的饮食看起来不错,但是现在我们知道这是因为它们提供了有助于阻止过度炎症的分子的前体。”

医生过去认为,关闭炎症仅需消除引起炎症的原因,例如从手指上拔刺或在这种情况下去除细菌。尽管这有时可能会起作用,但我们现在知道,关闭炎症是一个活跃的过程,需要某种类型的抗炎分子。

与其他抗炎药不同,本研究中使用的特殊药物可减轻小鼠肺部的炎症,而不会抑制清除细菌的能力。实际上,它实际上可以加快清除细菌的过程。菲普斯和他的同事认为,他们是第一个证明这种特殊化合物在肺感染的情况下可以改善肺功能的药物。

尽管这些结果令人鼓舞,但需要进一步研究以了解这些化合物如何在人体中使用。滴眼液形式的类似化合物最近在临床试验中测试了干眼症,并且具有良好的耐受性。

如果发现对人类有效,则本研究中使用的药物可能会改善全球数百万患有COPD的人们的生活,也可能用于治疗耳部感染,支气管炎和肺炎,这也是由NTHi引起的。

Omega 3 Fatty Acids May Reduce Bacterial Lung Infections Associated with COPD - Newsroom - University of Rochester Medical Center

https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/news/story/4526/omega-3-fatty-acids-may-reduce-bacterial-lung-infections-associated-with-copd.aspx

Immunol Cell Biol. 2007 Apr-May;85(3):229-37. Epub 2007 Feb 20.

Pulmonary epithelial cells are a source of interferon-gamma in response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection.

Sharma M1, Sharma S, Roy S, Varma S, Bose M.

Author information

1

Department of Microbiology, VP Chest Institute, University of Delhi, Delhi, India.

Abstract

Recent report from our laboratory showed that A549 cells representing alveolar epithelial cells produce chemokine interleukin-8 and nitric oxide (NO) when challenged with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) played a critical role in priming these cells to generate NO in vitro. In the present study, we report that M. tuberculosis-infected A549 cells are capable of elaborating IFN-gamma as shown by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and intracellular staining for IFN-gamma. Secretion profile indicated that M. tuberculosis-infected A549 released significantly high concentration of IFN-gamma at 48 and 72 h post-infection. Low level of IFN-gamma release was also seen to be induced by gamma-irradiated M. tuberculosis and subcellular components of M. tuberculosis. Cell surface receptor analysis showed that the M. tuberculosis-infected A549 cells expressed enhanced levels of IFN-gamma receptors. This observation suggests that the endogenously produced IFN-gamma in response to M. tuberculosis infection plays a role in intracellular regulation of innate immunity against intracellular pathogen such as M. tuberculosis. This observation is further strengthened by the fact that infected A549 cells expressed signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1), an important mediator for IFN-gamma signaling pathway, leading to expression of inducible NO synthase and subsequent release of NO in sufficient concentration to be mycobactericidal. Our results show that production of IFN-gamma and enhanced expression of IFN-gamma receptors by infected A549 cells is a local phenomenon occurring as de novo intracellular activity, in response to M. tuberculosis infection. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to show that A549 cells interact actively with M. tuberculosis to produce IFN-gamma that might play an important role in innate immunity against tuberculosis.Pulmonary epithelial cells are a source of interferon-gamma in response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. - PubMed - NCBI

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17310225

Type I interferon response to extracellular bacteria in the airway epithelium

Affiliations

Department of Pediatrics, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA

The airway epithelium possesses many mechanisms to prevent bacterial infection. Not only does it provide a physical barrier, but it also acts as an extension of the immune system through the expression of innate immune receptors and corresponding effectors. One outcome of innate signaling by the epithelium is the production of type I interferons (IFNs), which have traditionally been associated with activation via viral and intracellular organisms.We discuss how three extracellular bacterial pathogens of the airway activate this intracellular signaling cascade through both surface components as well as via secretion systems, and the differing effects of type I IFN signaling on host defense of the respiratory tract.

1型干扰素对呼吸道上皮细胞外细菌的应答

呼吸道上皮具有多种防止细菌感染的机制。它不仅提供了一个物理屏障,而且通过表达先天免疫受体和相应的效应器来作为免疫系统的延伸。上皮细胞先天信号转导的一个结果是I型干扰素(IFNs)的产生,这种干扰素传统上与病毒和细胞内生物的激活有关。

我们讨论了呼吸道的三种细胞外致病菌如何通过表面成分和分泌系统激活这种细胞内信号级联,以及I型干扰素信号对呼吸道宿主防御的不同作用。Type I interferon response to extracellular bacteria in the airway epithelium: Trends in Immunology

https://www.cell.com/trends/immunology/fulltext/S1471-4906(11)00151-7

Alpha interferon is produced by white blood cells other than lymphocytes, beta interferon by fibroblasts, and gamma interferon by natural killer cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (killer T cells). All interferons inhibit viral replication by interfering with the transcription of viral nucleic acid.

Alpha interferon | biochemistry | Britannica

www.britannica.com/science/alpha-interferon

J Clin Immunol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 May 1.

Influenza-Induced Production of Interferon-Alpha is Defective in Geriatric Individuals

David H. Canaday, Naa Ayele Amponsah, Leola Jones, Daniel J. Tisch, Thomas R. Hornick, and Lakshmi Ramachandracorresponding author

Author information Copyright and License information Disclaimer

David H. Canaday, Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center (GRECC), Cleveland VA Medical Center, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA; Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA;

Abstract

Background

The majority of deaths (90%) attributed to influenza are in person’s age 65 or older. Little is known about whether defects in innate immune responses in geriatric individuals contribute to their susceptibility to influenza.

Objective

Our aim was to analyze interferon-alpha (IFN-alpha) production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated from young and geriatric adult donors, stimulated with influenza A or Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands. IFN-alpha is a signature anti-viral cytokine that also shapes humoral and cell-mediated immune responses.

Results

Geriatric PBMCs produced significantly less IFN-alpha in response to live or inactivated influenza (a TLR7 ligand) but responded normally to CpG ODN (TLR9 ligand) and Guardiquimod (TLR7 ligand). All three ligands activate plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs). While there was a modest decline in pDC frequency in older individuals, there was no defect in uptake of influenza by geriatric pDCs.

Discussion and Conclusion

Influenza-induced production of IFN-alpha was defective in geriatric PBMCs by a mechanism that was independent of reduced pDC frequency or viability, defects in uptake of influenza, inability to secrete IFN-alpha, or defects in TLR7 signaling.

Keywords: Aging, influenza, interferon-alpha, plasmacytoid dendritic cellsIntroduction

Over 32,000 deaths per year occur in a typical influenza season with over 90% of deaths in persons over 65 years of age [1]. With the current H1N1 global pandemic, the number of influenza cases is expected to dramatically increase resulting in greater numbers of deaths than usual even in individuals over age 65. They are less susceptible than younger individuals to 2009 H1N1 but continue to have greater risk of complications if they develop active influenza infection. Unfortunately, the seasonal influenza vaccine has poor efficacy in this older group. The rates of protection against hospitalization for influenza and pneumonia are estimated to be only 33% in individuals over age 65 [2]. A better understanding of the pathogenesis of influenza infection and disease in older persons is required to develop more effective vaccines or immunomodulatory strategies to reduce morbidity and mortality in this group.

There are likely multiple mechanisms for this increased morbidity and mortality with aging. While decline in T cell function has been extensively documented in the elderly [3–11], potential changes in immune function that impact innate anti-viral responses have been largely unexplored. Type I interferons (IFNs) were first identified for their antiviral properties against influenza [12, 13] and have been subsequently shown to induce the transcription of several genes that help degrade viral RNA and block viral replication [14–16]. In addition to their anti-viral properties, type I IFNs have multiple effects on human mononuclear populations including T cells and B cells, and reduced type I IFN production could result in decreased induction of cell-mediated immunity [17].

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) are the main producers of type I IFNs after influenza activation [18]. Influenza virus ssRNA induces expression of type I IFNs in pDCs via activation of Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) [19–21]. IFNs induce expression of MxA, a protein with anti-viral activity [22–24] that renders pDCs resistant to virus-induced apoptosis [25]. pDCs have been found in all of the relevant respiratory mucosal sites in humans including nasal mucosa, lung, and bronchalveolar lavage fluid [26–29]. In the influenza challenge mouse model, pDCs in the respiratory tract were found to make two-thirds of the IFN-alpha generated supporting the idea that pDCs in spite of their low numbers in respiratory mucosal sites produce the majority of IFN-alpha [30].

Several animal models suggest a clear role for IFN-alpha in protection against influenza. Ferrets and Guinea pigs have been found to be representative models of human disease as they are susceptible to human influenza strains, are able to transmit infection [31–33], and express the MxA gene [34]. Recent studies in ferrets and Guinea pigs show that exogenous IFN-alpha reduces viral shedding and morbidity to influenza A virus [35, 36]. The mouse model has shown variable results regarding the importance of IFN-alpha as many of the studies use BALB and B6 mice that lack the MxA gene [34].

In the current study, we have assessed response of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated from control (<35 years) and geriatric (>65 years) individuals to live influenza. IFN-alpha production was significantly reduced in pDCs from geriatric individuals in response to influenza but not to other TLR ligands that also activate pDCs.

Results

PBMCs from Geriatric Individuals Produce Less IFN-Alpha in Response to Influenza than PBMCs from Younger Controls

Influenza Activates pDCs Via TLR7

Geriatric PBMCs Have Reduced Frequency of pDCs

Geriatric PBMCs are not Defective in Production of IFN-Alpha in Response to TLR9 Ligand CpG ODN or Other TLR7 Ligand Guardiquimod

Geriatric pDCs are Not Defective in Uptake of Influenza A

In conclusion, geriatric pDCs were defective in the production of IFN-alpha in response to influenza A by a mechanism that was independent of reduced pDC viability, defects in uptake of influenza, inability to secrete IFN-alpha, or defects in TLR7 signaling.Discussion

Susceptibility of older individuals to influenza has often been ascribed to defects in T cell function. The contribution of the innate immune response to this defect remains unclear. Innate immune responses to influenza consist importantly of vigorous production of type I IFNs. They are potent anti-viral cytokines that also regulate other aspects of innate and adaptive immunity. We observed a significant decrease in the levels of IFN-alpha in supernatants from geriatric PBMCs activated with influenza. Surprisingly, no defect in IFN-alpha production was observed in geriatric PBMCs activated with CpG ODN 2216 or Guardiquimod. While influenza activates pDCs via TLR7, CpG ODN 2216 and Guardiquimod activate pDCs via TLR9 and TLR7, respectively. Our observations clearly indicate no defect in TLR7 or TLR9 signaling or IFN-alpha production in the pDC population in the elderly. Consistent with our findings, Jing et al. recently reported that the frequency of IFN-alpha secreting pDCs was reduced in PBMCs from healthy elderly subjects activated with influenza but not CpG 2216 [47]. We also observed a decline in pDC frequency in the elderly similar to that reported by other groups [47– 49]. Less IFN-alpha secreting pDCs coupled with decline in pDC frequency in geriatric PBMCs may account for the decreased response to influenza in geriatric PBMCs. But geriatric pDCs would have to make more IFN-alpha on a per pDC basis in response to Guardiquimod and CpG ODN 2216 (Fig. 6) to account for their normal response to these ligands despite lower pDC frequency.

Defect in IFN-alpha production in geriatric pDCs was only observed with influenza but not with other ligands that also target intracellular TLRs in pDCs. Interaction of ligands with TLR7 and TLR9 occurs in acidic endocytic vesicles, is pH dependent and is abrogated by agents like chloroquine and bafilomycin A that increase endosomal pH [44–46]. Interaction of influenza viral ssRNA with TLR7 requires virus fusion and uncoating from endocytic vacuoles by a process that is pH dependent and occurs in late endosomes through a type I fusion process [53, 54]. Wang et al. demonstrated that increasing intraendosomal pH from approximately 4.5 to 5.2 with chloroquine significantly decreased IFN-alpha production in human pDCs in response to influenza virus but not to TLR7 ligand R848 that is an imidazoquinoline compound like Guardiquimod [55]. Increasing intraendosomal pH to 5.8 abrogated IFN-alpha production in response to both R848 and influenza. Therefore, subtle variations in late endosomal pH may impact IFN-alpha production in response to influenza but not other TLR7 ligands. We speculate that a slight increase in pH in late endosomes (and maybe all endosomal compartments) in the elderly may impact influenza virus fusion and uncoating and lead to inhibition of IFN-alpha production in response to influenza (which is very pH sensitive) but have little impact on IFN-alpha production to other TLR7 and TLR9 ligands (which may not be as pH sensitive).

The intracellular location of a TLR ligand may also determine the resulting biological response [56]. In human pDCs localization of CpG ODNs to transferrin-receptor-positive early endosomes led exclusively to IFN-alpha production while localization of CpG ODNs to LAMP-1 positive late endosomes promoted maturation of pDCs [56]. Similarly, in murine pDCs retention of Type “A” CpG ODN in endosomal compartments promoted IFN-alpha induction [57] while rapid transfer to lysosomal vesicles, as seen with conventional DCs, led to little IFN-alpha production. When Type “A” CpG ODN was manipulated for endosomal retention, robust production of IFN-alpha was observed [57]. In geriatric pDCs, viral ssRNA may be rapidly transferred to lysosomes, resulting in reduced IFN-alpha production.

Entry of influenza virus into cells has been studied extensively and involves binding of the virus to sialic acid-containing receptors on the cell surface followed by internalization by receptor-mediated endocytosis [58]. Since decreased uptake of influenza virus by geriatric pDCs may also lead to decreased IFN-alpha production, we compared uptake of FITC-labeled virus in geriatric and control pDC by flow cytometry. No defect in uptake of influenza by geriatric pDCs was observed. Although the experiment was designed with an incubation period to allow virus to bind cells, followed by a chase period to maximize uptake of virus, the possibility that virus remained on the cell surface cannot be ruled out.

In addition to their anti-viral properties, type I IFNs mediate both innate and adaptive immune responses. Therefore, reduced IFN-alpha levels in geriatric individuals after influenza stimulation could have a number of deleterious effects on both innate and adaptive immunity in older adults. Type I IFNs can induce the production of multiple cytokines, chemokines, and other molecules like IL-15 [59], CCXCL10, CCL4, CCL2, and IL-1RA [60]. Type I IFNs have been shown to play a modulatory role in differentiation of human T cells to Th1 development [61, 62] and in the development of CD8+ T central memory cells [63, 64]. Presence of IFN-alpha was shown to have mixed effects on proliferation in human memory CD4+ T cells depending on the antigen stimulation [65]. In murine systems, type I IFNs act directly on both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to allow clonal expansion in response to viral infection [66, 67]. An in vitro study by Jego et al. [68] using human DCs and B cells showed that IFN induces activation and IL-6 secretion by DCs, which was required for differentiation of B cells into antibody-secreting cells. Isotype switching of B cells is also enhanced by type I IFNs [69]. In murine systems, following influenza virus infection, type I IFN receptor signals directly activated local B cells [70] and type I IFN directly modulated respiratory tract B cell responses [71]. Type I IFN has also been shown to enhance B cell receptor-dependent B cell responses [72]. A number of DC functions are enhanced by type I IFNs including MHC-I cross priming and DC maturation [73– 75]. Therefore, innate immune defects in IFN-alpha production by older individuals could lead to multiple defects in their adaptive immune responses.

Conclusions

Geriatric PBMCs made significantly less IFN-alpha in response to influenza than PBMCs from younger controls. This could have a deleterious effect on anti-influenza responses in geriatric individuals and contribute significantly to the susceptibility of older individuals to influenza.Influenza-Induced Production of Interferon-Alpha is Defective in Geriatric Individuals

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2875067/

Circulating, Interferon-Producing Plasmacytoid Dentritic Cells Decline During Human Ageing

Scandinavian Journal of Immunology, 2002